Second season! Mostly a figment of storm chasers’ imaginations, second season consists of the very, very modest uptick in severe weather climatology across the traditional tornado alley in early fall as the jet stream noses southward. Of course, this is balanced against total daylight hours that are essentially equivalent to early March, and often meager thermodynamics that are dependent on just-right return flow and an impinging EML. Since arriving at OU in 2016, a comprehensive list of my at-all-fun-or-notable storm chases: 10/04/16, 10/21/17, and that’s it. A 4-year gap engenders much cynicism.

Still, by the beginning of October it was pretty clear that the central and southern Plains were going to see at least somewhat favorable conditions for severe weather. A big trough was going to come ashore out west, with a moist tongue variably forecasted to end up making it somewhere to somewhere between Childress and McCook. At times, the setup looked really good – too good to be true, as all seasoned forecasters are trained to expect. And indeed, we were cursed with the presence of a prior event on Sunday, October 10. I’ll skip the heavy details for now, since I plan on looking more in-depth into the events of October 10 in my upcoming Great Sand Dunes National Park blog posts, but the gist of it: a marginal event did the thing were suddenly it looks incredible, popping into a day-1 15-hatched moderate risk in southwest Oklahoma – while I was driving back from southeast Colorado. A lone supercell developed out of a morass, dropped some impossible-to-see tornadoes, and the ensuing front scoured moisture to I-10, possible ruining Tuesday.

When I woke up Tuesday morning, things were still quite touch-and-go on the tornado front. I wasn’t particularly enthused, but there certainly was a tornado risk.

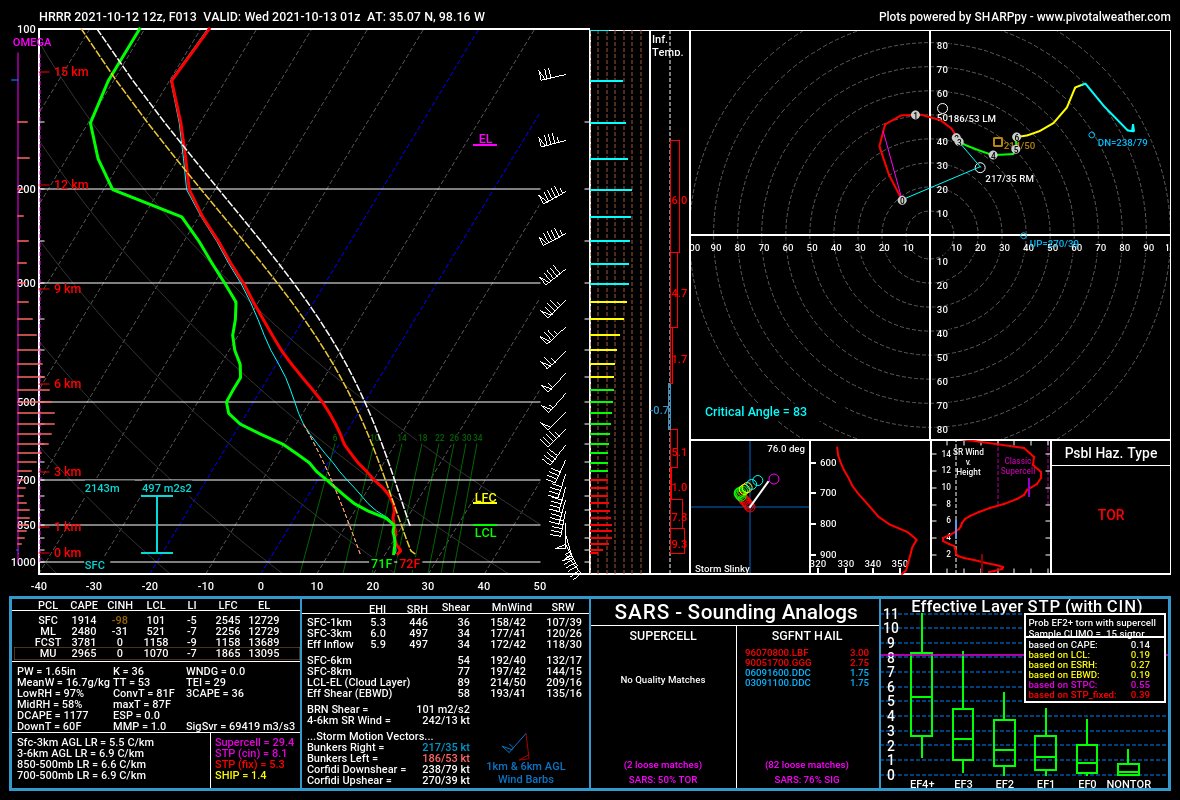

Was the best risk a bit far for my liking? Yes. I would drive that in a heartbeat for diurnal convection, but in this case the main threat was expected to ramp up pretty rapidly after dark. Would storms be surface-based? Would they be discrete? Would they be moving too fast to chase? It all remained to be seen. All I knew was that the environment in my morning target of Cordell, OK looked like this:

Howie Bluestein finished off our convection class with a hilarious weather briefing. In it, he used the notoriously cold-biased low-resolution NAM to forecast the nocturnal threat, and became correspondingly despondent until he looked at the 15Z HRRR and saw a UH track headed right up I-44. Then he started making plans for his RAX-pol deployment. Just as class ended, Jason Chiappa, my classmate, asked if I had chasing plans. Sam and I were loosely ready to launch yet another desperate Southern Plains Multicell Chasers venture somewhere, and I told him as long as he was good with dealing with Scipio in the car I didn’t mind if he came with us.

Not that I was entirely convinced we were actually chasing. The early afternoon hit its usual forecasting nadir before the mid-afternoon improvement. Sam and I ate lunch on the NWC patio and I probably hit 8 snarks out of 10 talking about the setup. When I got back home, though, it became clear that thermodynamics were overperforming in the warm frontal region of southwestern Oklahoma. The HRRR showed a narrow corridor from about 8:00 p.m. to 10:00 p.m. where supercells could be discrete and surface-based in an insane kinematic environment from about Lawton northwestward to Seiling. Unfortunately, the actual UH tracks were sliding ever further north as they did the usual HRRR thing and became super numerous. I wasn’t terribly enamored with the northern target (storm mode and capping concerns kept me from ever seriously considering Kansas), but chasers were strung out all the way up to Colby. And they weren’t the only ones.

I still really wanted things to pop further south. Anything but a nocturnal trip to the literal Oklahoma panhandle on a school night would have been the preferable option to me. And, in fact, a cumulus field began to develop right where I wanted it.

The afternoon drifted toward the evening. Sam and I plotted while I talked to Jason Myers. A few blips showed up on radar all the way near Abilene, well south of anyone’s radar. Of course, Jason was prepared to be all over those blips as they were headed right toward the Wichita Falls region. I trained my eyes on one further to the west, which was flying up toward Quanah at 5:00 p.m. At this point, I was ready to get either west or southwest to prepare, but Sam was not ready to go until 5:30. This began the most hilariously timed storm chase, *leaving home* just 90 minutes before sunset. Fortunately, Scipio was pretty good about meeting Jason. Unfortunately, Scipio was not in a settled mood, and would be a continued source of stress throughout the coming evening, which was far from calm. We decided to head west on 40 and commit to the little blip flying north from Quanah as it slowly rooted itself into the unstable surface layer.

My car needed gas and I felt like we were about 60 minutes late to the storm, but otherwise, things generally felt like they were falling into place. By the time I got the chance to take a break from driving 85 mph down I-40 to get gas in Bridgeport, I had the chance to look at radar and see that our blip was developing into a bona-fide if still somewhat flawed supercell. It was trying to turn right, which would hopefully allow us to intercept it before it crossed I-40. And it wasn’t moving too fast, a critical development in a world where the uncapped warm sector had a strict northeastern limit. I ran the gas stop like a NASCAR pit stop, taking Scipio to pee and directing Sam to get Love’s chicken tenders for himself all in the span of like 3 minutes. In my eyes, this supercell had a chance to go rapidly tornadic, and we didn’t want to miss it.

It wasn’t long before the storm actually became tornado-warned. We couldn’t quite see the updraft in the light of the sunset as we flew past Weatherford, but the storm loomed in the distance. Livestreams reported decent-sized lowerings heading toward I-40. Where at? Jason and Sam tried to figure it out, variably coming up with answers of Foss, west of Clinton, or Clinton itself. But it became clearer and clearer – even as we lost twilight rapidly on a pretty cloudy day, we had won the race for the I-40 crossing. I zipped on in to the outskirts of Clinton and pulled south on 183, bound for Bessie. Lightning flashes picked up from the southwest – first flashes, then in-cloud strikes, then finally the distant zaps of cloud-to-ground lightning. I raced the forward flank south on 183 and breathed a sigh of relief as the sounds of “The Greatest Show” eased us into the inflow region. And man, what a sight that storm was by this point – a murky, twilit updraft that screamed “Plains Supercell”, cross-lit by flashes of lightning and a massive inflow tail racing in from the clear air directly south of it. As a driver, I have zero pictures, but all of these visuals can be found in Jason’s youtube video which I’ve linked.

After a small mixup on where exactly I needed to pull off on 183, we crested a hill east of 183 on 54A outside of Bessie to get a look at the storm. The base itself was either obscured in the rapidly fading light, or it was unimpressive.

What was incredibly impressive from our vantage in the inflow region was the sheer amount of inflow wind. It was purely howling. Scipio could barely stand to face into the wind, getting pelted with tumbleweeds as he was. Jason’s tripod, a fairly professional-looking rig, crashed to the ground almost the moment he set it up. And the inflow wasn’t exactly cold but it wasn’t exactly pleasant, either. We didn’t stay long before, shouting above the wind, Sam yelled that we needed to get back north toward Clinton to beat the storm and keep it from cutting us off from I-40.

Along the way back north, we passed Howie and RAX-pol, ironically enough. The last of the light leaked out of the day, leaving us straining for a visual in pure darkness and aided by infrequent lightning that seemed mostly concentrated in the forward flank. Not generally the best sign. As it was, we let the storm pass close to us before opting to get east on E1070 for six miles and cutting north on N2310. Even that was an adventure. The shitbox was buffeted by sustained inflow that had to be in the range of 30 knots, with an all-out attack of tumbleweeds in my face. The road was pretty small and at one point sharply curved to avoid a small creak, sending Scipio flying across Sam’s lap. To make matters worse, a dude followed right behind us with the most blinding headlights I’ve ever seen. It was a long couple of minutes before we started heading back north.

At this point, I hadn’t seen anything noteworthy under the base. A blip by Abilene had rooted and was tornado warned all the way south by Frederick and heading up into the Wichitas. All things considered, it would not have been impossible to try to cut south and meet it on the north side of the wildlife refuge, especially as we were just now entering the 8:00-10:00 window that I had identified as the prime time for tornadoes. I-40 was the ideal time to bail, and I at least raised the subject. Nobody objected too strenuously to the concept of bailing, but Sam said that we should pull of I-40 and give it a little bit longer. It was only then that I learned our storm wasn’t even tornado warned anymore, which felt like a little kiss of death to those insane hodographs I had been envisioning. Hope began leaking out of me; at least we could be home by 10:00 if the storm crapped itself out like it seemed like it was.

A long-duration strike of lightning lit up the sky west of us. I got a brief glimpse of something… “Whoa. Ok. Big, scuddy wall cloud just west of us.” I wasn’t sure if what I’d seen was true. The three of us anxiously craned our necks to the left, waiting for the next flash. Here it came, and Sam and Jason saw it too. The chase was back on. I drove past I-40 and found a little rise in the ground less than a mile north of the interstate to pull off on in between a few cars. Scipio twitched in my lap, then settled back down. I pulled out my phone and started to take a video on it. More lightning.

Jason said hesitantly, “It kinda looks like a funnel.” I tended to agree with him. Knowing that there wasn’t a tornado warning, I cut off my video after 15 seconds, then scrolled through to find a screengrab to send to NWS Norman.

Lightning illuminated again. “That’s a tornado!” “It’s on the ground!” I was just a half a second ahead of Jason in realizing what we were seeing. The pace of strikes was picking up, illuminating a slender, tapered cone 3 miles to our west-northwest. I hadn’t even had time to scroll away from my tweet to NWS Norman, and I had the great honor of giving them their first confirmation of a tornado from an unwarned storm:

Our little tornado friend continued to be accented by lightning flashes as it moved obliquely to us. At times it was a tapered cone, at times it lost its condensation funnel to the ground. Still, it continued onward, with each visual punctuated by enthusiastic cheers from somebody standing outside the car behind us.

After a few minutes, Sam informed me that it was time to leave and get north to pursue. I threw the car in gear and we began a complicated stairstep that I could never retrace on Google Maps, keeping the tornado or wall cloud or whatever we saw to our northwest.

At one point, we came upon a little ridge and to our shock, saw a massive wall of cloud reaching down to the horizon. “Is that a wedge??? I asked. Next flash, Sam screamed, “AHH WEDGE!”

Alas, we crested the ridge and discovered that it was not in fact a wedge, but just the wall cloud. We had wasted a perfectly good scream on a false alarm.

Eventually, the storm started to show signs of both occlusion and outflow-dominance. A big old bear’s cage presented itself as we got into position to make another play on 54 between Weatherford and Thomas. Due west of us, it didn’t really look inviting. There wasn’t a whole lot else to the storm that suggested we were gonna have a good time continuing to chase it to the north and east past the Canadian. Plus, there was another option on the way back. Jason Myers was still on the southern storm and dominating hard.

We could try to drop south out of Weatherford and intercept that storm around Fort Cobb. I gunned the Mariner through a weird fog bank southbound on Highway 58 until we got to Carnegie. It was here that Sam and I, who had been having an absolutely perfect night chasing so far, got greedy. We tried to blast south and slice around the supercell near Apache, but were blasted by blinding forward flank precip not far south of Carnegie. We had to turn around and try a slightly less blinding core punch eastbound to Fort Cobb. I gripped the wheel while Scipio hung on to my lap for dear life. Finally, the road started to come back into view more than 20 feet beyond the hood – just in time for us to crest a long ridge with a 0.2 Byers Barrage level of CGs raining down around us. Finally, everything settled down as we pulled into the outskirts of Anadarko. The moon was out, framing intermittent views of the updraft… and little else. The chase was over.

All things considered, we weren’t out too late. I took Scipio back up into our apartment a little after 11:00, in plenty of time to keep Elizabeth from being too mad. Even more impressively, we had managed to snag a highly visible nocturnal tornado from the perfect vantage point. It made a perfect bookend to the 2021 season.