I’ve been inside two SPC High Risks in my life. One was on my 16th birthday – November 17, 2013 – and ended with me within a few miles of a heavily rain-wrapped EF2 tornado near Kokomo, IN. And then… there’s May 20, 2019.

I’ve never seen a day like it. This was the day *3* convective outlook:

Even before the May 17-18 TORUS deployments, we knew this had the potential to be the big show. Mike was looking at the NAM before we’d even gotten home from our May 18 deployment. With May 19 looking like a brief respite before the big event:

We took the day down in Norman. We did know that the 20th was going to be rugged, and early-starting, so Elizabeth and I remained on call throughout the day in case the entire convoy decided to predeploy westward.

In line with the afternoon outlook, we got the call – everyone would be heading to Altus the night before. Thus, Elizabeth and I headed up to the Weather Center toward afternoon. I met Mike and Liz to load up the lidar truck with luggage, and we headed off down I-44 toward the Wichitas. The conversation along the way was oddly philisophical – a lot of talk about maintaining a balanced skillset in one’s career and always honing your toolbox. The three of us didn’t talk much about weather – perhaps because we were all on edge about what was going on. You don’t have to be a meteorologist in Oklahoma to know what tornadoes have done to places like Moore, El Reno, or Woodward. And yet, three years into my time in the state, nothing horribly bad had happened. But tomorrow, all of our homes were in the line of fire.

The Hampton Inn in Altus lies on the north side of town, sharing a parking lot with a soon-to-be-infamous Applebee’s. Glen and I checked in to our room and got ready to check into the grab dinner from the Applebee’s. I was briefly detained by #science – Liz and Mike wanted to run the lidar all night to sample the onset of the low-level jet. Despite the fact that I never got to see the data, I helped Liz by slowly guiding the truck (which I was still terrified of running into something) into a remote corner of the Hampton Inn so that she could plug the lidar system in and let it run all night. Eventually, I left her to her scheming because I needed a stiff drink. Or two.

Wouldn’t you know it, the entire storm chase and scientific research community appeared to have descended on this particular Applebee’s. I found the OU TORUS people clustered around the bar, rapidly getting rowdy. When I discovered why – dollaritas – I joined in on the fun. The poor bartender was making new vats of margarita as fast as she could while we were knocking them back.

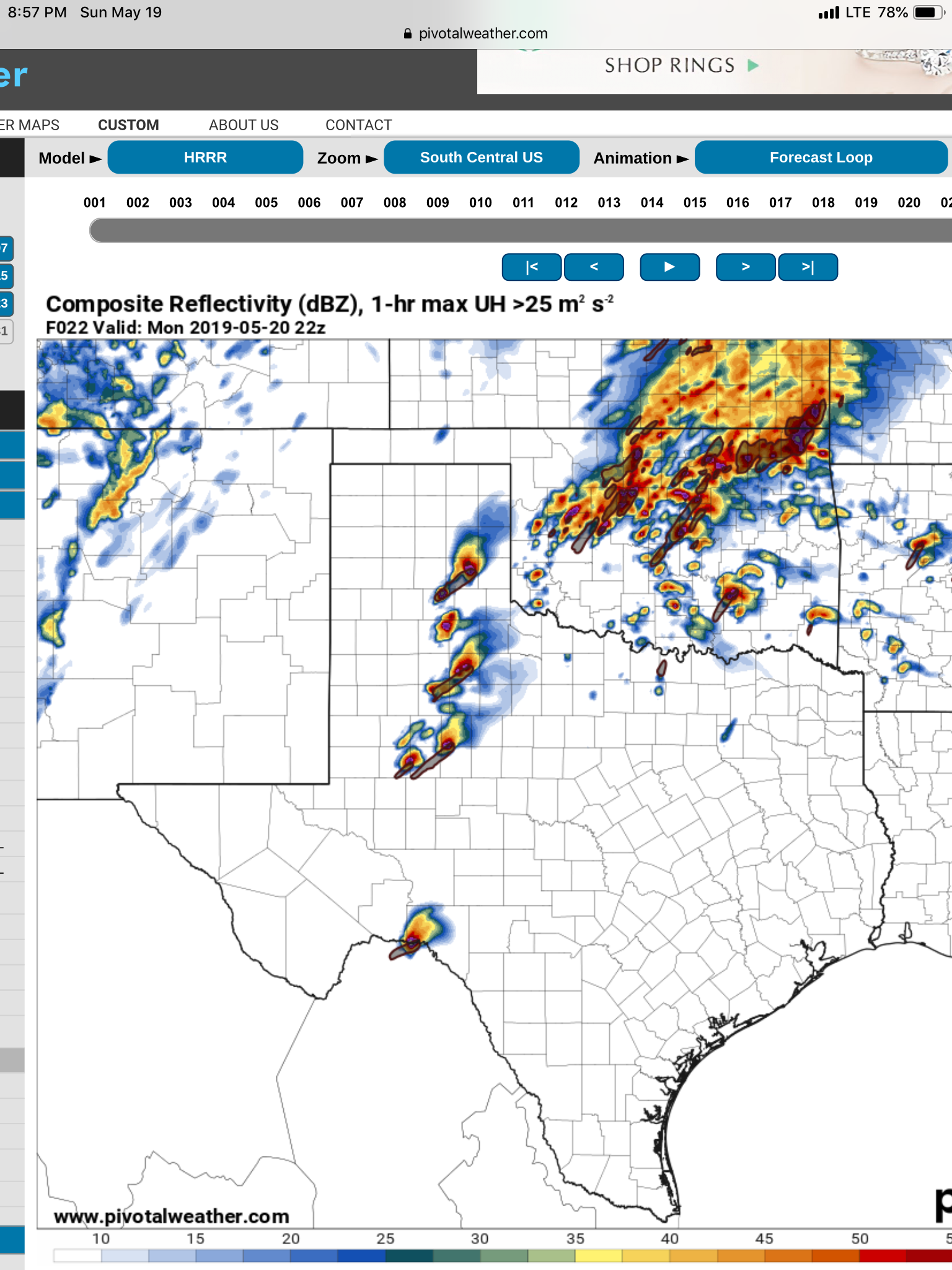

The vehemence with which we drank was not exactly slowed when the 0Z HRRR started to become available.

A dryline popping discrete, scattered supercells while the open warm sector convects monstrously. The parameter space was off the charts – 3,000 MLCAPE, up to 500 0-1 SRH. It looked like nothing so much as April 27, 2011. So yes. I drank dollaritas with a vehemence. Hell, even Elizabeth drank like 3. Sean Waugh drank 14 of them. Liz, who was with the lidar until after Applebee’s had cut off their food, had dollaritas for dinner (and then apparently retired to her hotel room, where she watched pet adoption videos on local TV and cried, in one of the most relatable stories I’d ever heard).

I woke up in the morning with the taste of cotton balls in my mouth and a burning question. Had the SPC gone high risk? Answer: yes.

A 30% hatched risk of tornadoes was in place, the first we’d seen in Oklahoma since the infamous May 18, 2017 outbreak that I watched from the Mesonet. The wording of the SPC outlook specifically mentioned:

A cluster of tornadic supercells is then forecast to move northeastward into northwest Texas and the southeastern Texas Panhandle during the early evening. Additional tornadic supercells are forecast to rapidly develop in southwest Oklahoma and move northeastward into west-central Oklahoma. At that time, the strengthening low-level jet will couple with a highly progressive and seasonably strong mid-level jet, making conditions favorable for long-track strong tornadoes and possibly violent tornadoes.

Very casual stuff. The environment was primed for severe weather insanely early:

That warm front was lifting north and bringing low-to-mid-70s dewpoints into the region. Lapse rates from Kiel’s pre-8:00-a.m. sounding ranged well above 7 C/km, and the low-level jet was only going to intensify as the day went on. In fact, already storms were beginning to develop and intensify into severe hail producers out in the Texas panhandle, establishing a cold pool.

Before I’d even left my hotel room, I’d fired off a preparedness thread that, by my standards, was pretty emphatic:

I went downstairs to load up on the Hampton Inn’s continental breakfast. I love storms. I love storm chasing. I loved being part of TORUS. But right then, I was not having fun. All I could think about was my poor stuffed hedgehog, Hector, left in Elizabeth’s apartment in Norman. If her apartment got hit by a tornado and he was lost or destroyed I was never going to forgive myself…

To steady my nerves, I wrote about the previous chase in my very-soon-to-be-abandoned journal. Everybody was talking about today; even Hampton Inn guests unrelated to the weather were asking TORUS chasers about whether or not they should rethink travel plans. It was a lot to process.

The weather briefing, held at the hotel used by other universities within the TORUS team, may have been the most tortuous of all the weather briefings. There are a lot of CAMS out there in the world, and it seemed that the grad students leading today’s weather briefing were intent to look at every single one of them. They were all apocalyptic. At some point, you get diminishing returns when you determine if the 12th member of an ensemble is putting its tornadic supercell through Hollis or Altus. In essence, there were going to be three or four rounds of severe weather. The first, ongoing north of the warm front, was expected to evolve into an MCS and possibly ride the warm front over north central Oklahoma later in the day. The second round was expected to develop in the Texas panhandle by early afternoon, with discrete tornadic supercells likely. The third round, kicked off by the dryline, would be more tornadic supercells down the dryline into west Texas, moving into northwest Texas and southwest Oklahoma later in the day. The fourth round, with the timing most uncertain, would be initiation within the open warm sector into central Oklahoma. When this occurred, the expectation was that we could see something like April 27, 2011 – tornadic supercells galore.

How to position for that? The debate dragged on. Sean grew so impatient that he left the meeting. Finally, a consensus was reached. We would begin by targeting the second round, near the outflow boundary. As the day went on, we could drop south onto more tornadic storms as conditions allowed.

I hopped into the driver’s seat of a fairly muted lidar truck, en route to Sayre. Along the way, we passed through the beautiful Quartz Mountain range – a moment of serenity. The morning visibility was crappy – with all of the moisture return, there was a very low cloud deck. Meanwhile, wildfires in Mexico had led to the development of a massive smoke plume which had been advected north right into the area. Everywhere you looked was grey, just grey.

By the time we got near Sayre, a few breaks in the clouds had developed. “Cloud cover” being one of my anticipated failure modes, alone with “overconvection in the warm sector”, I was starting to lose the doubts I usually harbor on big days panning out.

We got to Sayre and began another TORUS takeover – this time, of a Flying J Travel Plaza. It was only late morning, but already we were on high alert. The signs continued to point toward an extremely high-end day.

I finally had time to read the 16:30Z outlook, issued on the way to Sayre. I’ll probably never be in an outlook like this again.

The miasma of low clouds continue to rip northward just off the deck. Occasionally, little showers would pass over us, bringing wind-driven rain to the Flying J parking lot. Occasionally, other chasers would pull up alongside us and take pictures, or greet the people from OU they knew. We saw an old undergrad acquaintance, Tabbs, and Reed Timmer’s extreme drones team. But at this point, it was mostly a waiting game.

Liz, Mike and I snuck across the street to McDonald’s briefly. We ate in the car on the chance that CI occurred while we were eating. Fortunately, it didn’t happen, and we returned to the other side of the road to rejoin the convoy.

Back to watching and waiting, watching and waiting. Storms continued off to our north, on the other side of the warm front. Which, looking at the Mesonet…

I sidled over to Erik Rasmussen, sitting inside Mobile Mesonet 2. “Hey, Erik, don’t you think we need to get south? The winds here are out of the north.” The cold pool established earlier that morning had continued to push southward. Suddenly, despite being in the 45% tornado risk, Sayre had become completely choked off from the unstable airmass. Erik looked around, felt the breeze through his window, and nodded in agreement. N0w, I was a nobody on this project – some near-minimum-wage labor that they paid to drive the truck without complaining. But still, I’d talked to one of the most formidable tornado research scientists in the world, and he’d agreed with me (in fact, he’d probably known that long before I said something, and the fact that I caught it told him it was really time to go). Erik got on the TORUS chat client and began to round up the troops for a southward push toward Hollis.

This, for me, was the first indication that something was *wrong* with the setup (wrong, of course, depending on your point of view). But even as we had waited in that Flying J parking lot, sobering indications had poured in from every direction.

Even the belated initiation of storms was more of a cause for concern than anything else. A subtle inversion had appeared on the 18Z FWD sounding (maybe visible slightly in the TORUS sounding as well) that appeared to be tamping down CI in the warm sector, meaning that storms that did initiate (with a bubbling CU field already noted) would likely remain discrete. As such, an extremely rare PDS tornado watch with all of the severe probabilities greater than 95 percent (including at least one significant tornado) was issued around 1:30.

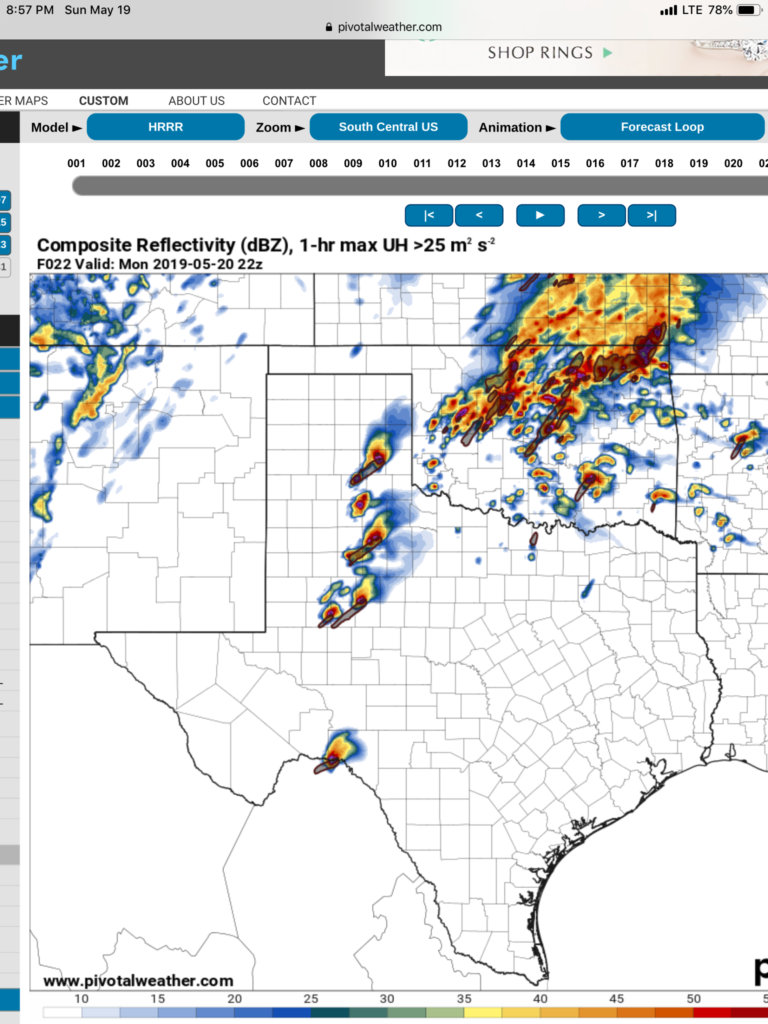

Meanwhile, we were on our way down State Highway 30 toward Hollis. Looking at the HRRR, this was not the wrong place to be.

Around 2:00, the bubbling cumulus field and light showers that had permeated the warm sector began to deepen into convection. While one storm seemed to initiate on one of the HCRs mentioned in the SPC MD, we were too far southwest to worry about that, targeting the more obvious storms that were going to initiate off the dryline. In particular, we were looking back toward the Paducah to Childress area.

Meanwhile, Mike, Liz, and I were navigating the Red River bottomlands, shooting for an ideal place to deploy the lidar. I know that within Mike’s head, the desire to get a once-in-a-lifetime dataset was warring with the desire to survive collecting said dataset. Given the persistent low cloud-cover and the approximately 60 billion chasers likely to be on a high risk in southwest Oklahoma, trying to deploy too close to a tornado carried its own risks. These warring considerations led us eastward on US-62, then southward, finally settling at a dirt-road intersection just off of State Highway 6. At about 3:30, we began the lidar deployment from there, looking at a still-multicellular collection racing up from north Texas toward the Red River. A fact that I think has been lost with time: this multicellular mix was really confusing to figure out in real time. Multiple tornadoes were reported near Paducah. We looked to be in perfect position to intercept them. Then, a new cell grew to the north and the initial supercell lost its definition. It looked like we would have to move north – we packed up the truck and got ready to go. Then, Mike changed his mind. We would stay where we were, deployed for nearly another full hour. I honestly don’t remember it being that long in hindsight. I do remember seeing on social media as a storm initiated near the warm front and produced twin tornadoes near Guthrie:

Meanwhile, our complex was becoming clearer. In a bit of a violation of the normal rule that the southern storm in a cluster is likeliest to become dominant, the northern storm in the Red River valley was clearly becoming dominant. This presented a problem to the TORUS team, spread out among the bottomlands – Mobile Mesonet 1 was already across the Red River, perhaps not a huge deal most days but a location that would prove impossible to overcome with limited crossings of the river and massive traffic. Meanwhile, some of the remote sensing instruments, such as us, were still well south of where this storm would actually cross. We frantically packed up and I yeeted northward onto Highway 34. This shot from my friend McKinsey shows the developing dominant supercell getting ready to cross US-62.

Once again, Mike tried to balance the difference between getting a good dataset and keeping us alive by choosing a pull-off 2 miles south of Duke. We got there at 4:50 and started scanning once more. In hindsight, two things are true at once. We were both much closer to the storm than I figured, and we also had literally no visual on the storm – updraft, mesocyclone, anvil lightning, anything. Just a persistent smoky haze. And ten thousand storm chasers late to the party zooming by us.

As we were scanning, a tornado developed about 10 miles to our north-northwest and tracked toward the town of Mangum. As it entered Mangum, a few chasers struck the motherlode with their view.

A lot more saw it hazily in the distance:

And then there were the people who drove by me while I was launching a balloon into the morass on the side of the highway.

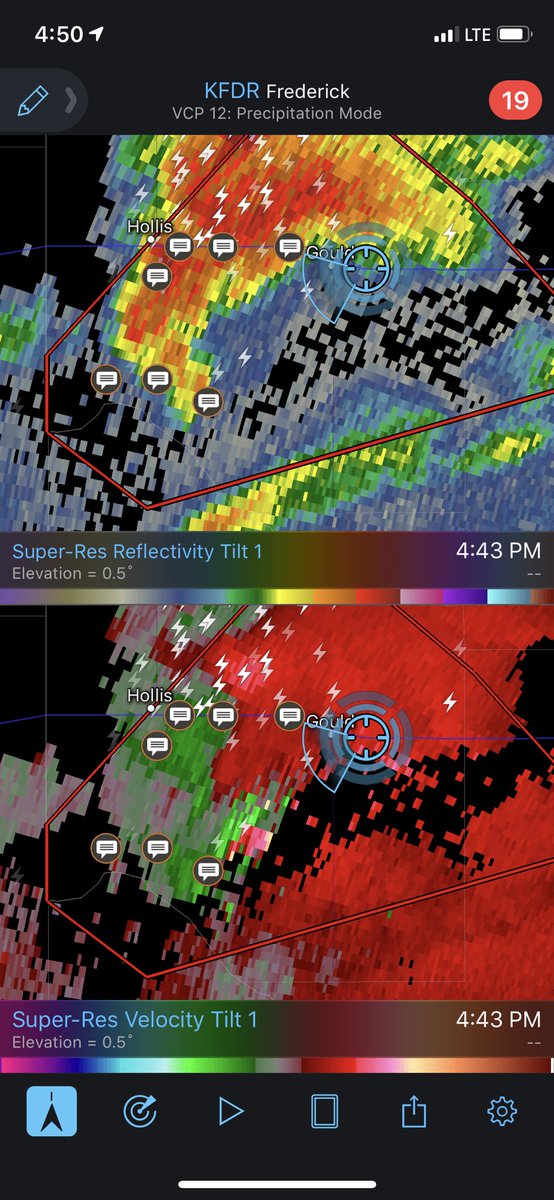

By the way, the storm had a good environment:

Without much scientific follow-up on the data, I’ll defer to Mike about whether the data we collected were useful. But the data certainly were fascinating: from the great distance of 10-15 miles from a significant (possibly violent) tornado, we experienced consistent ascent within the boundary layer for the entire second deployment – none of the usual vertical turbulence that characterizes a convective and even near-storm boundary layer.

Meanwhile, as a result of moving closer to the storm (and possibly the storm’s impact on the environment as a whole), the upper-boundary-layer saw a dramatic increase in horizontal wind speed, up to 30 m/s (60 kt) in the 1-2 km layer.

How much of this was our change in position, and how much was the storm’s influence on the environment? The scientists know more than me. What I know is that despite the visibility and the traffic, we succeeded in deploying on a significant tornado a few days after everybody else in the field project but us deployed on one in Nebraska. Meanwhile, to fully reverse the roles, none of the in-situ vehicles were able to get close enough to the Mangum monster to collect any useful data. This led to widespread frustration.

Meanwhile, in the lidar truck we were aimlessly wandering. We headed east out of Duke toward Altus in a very half-hearted attempt to keep up with the Mangum supercell, but it was racing off to the northeast (and not going to produce anything else useful anyway). So, we had come full circle to Altus. I pulled off on the side of US-62 downtown, where we spoke to several locals as Mike tried to gameplan a next move. The whole day, we saw, was coming unglued. The string of pearls coming off the dryline into southwest Oklahoma was really a whole lot of elevated and junky crap. The warm sector, outside of the first storm near Guthrie, has curiously failed to pop. And meanwhile, the cold pool from storms north of the warm front had continued to allow it to sag ever further southward into the warm sector.

Some more storms had developed back to our west. In the high-end outbreaks like today was supposed to be, tornadic supercells following closely in the path of previous tornadic supercells is actually pretty common. But in this case, although we made it as far north as we could out of Duke before deploying (the roads being closed due to a chaser accident near Mangum), the lowering of our storm was undercut at first sight (and ever so hazy).

Finally, off to the north the final death knell for the day appeared – a shelf cloud showing that the outflow boundary had made it all the way into southwest Oklahoma.

Consummate professionals until the end, the lidar team continued to scan as the cold pool gradually made its way overhead, providing the large vertical velocities seen in deployment 3 of our quicklook (this event would prove to be one of the more important capstone cases James and I used the following school year). Purely for shits and giggled, I launched a sounding into the oncoming density current. It floated upward momentarily, then as it got overtaken by the outflow, got battered back southward toward us. For a while the poor balloon was suspended, neutrally buoyant in the density current’s downdraft, before it managed to latch onto the forced ascent ahead of the density current nose and zoomed up into the pristine atmospheric ahead and above the density current. It was a fitting metaphor for the day.

It’s hard to assess how to feel when your scientific team has been preparing for an all-time outbreak, only for it to bust almost entirely. I certainly felt relief that a tornado hadn’t wiped out Hector and the rest of Norman, and relieved for the dozens of people spared by whatever went *wrong* in the environment. But still, when you’re there to collect data and completely are unable to do so, as most other members of TORUS were, there’s going to be frustration. Some of it, as shown in Matt’s tweet, was channeled into ire at the hordes of chasers that blocked the path to the one viable storm. Some of it was directed internally, with the inevitable conflict between researchers forced to be cooped up in trucks and hotels rooms with each other for six weeks erupting. And some of it was just channeled into exhaustion, and the desire to just get home and forget about the day. A group of OU researchers including the NOX-P radar team and the lidar team met up at the Lawton Buffalo Wild Wings to grub up before taking I-44 home. The thing I remembered most was the general sense of disbelief – how had this environment busted? On paper, it was the perfect setup.

In the coming days, there would be an effort on social media, led by well-intentioned meteorologists who don’t want to see the public lose faith in our forecasts, to say that the setup hadn’t busted. This was bolstered later that night when a QLCS developed and rampaged through what remained of the warm sector, dropping a tornado just a few miles from where I slept unsuspectingly.

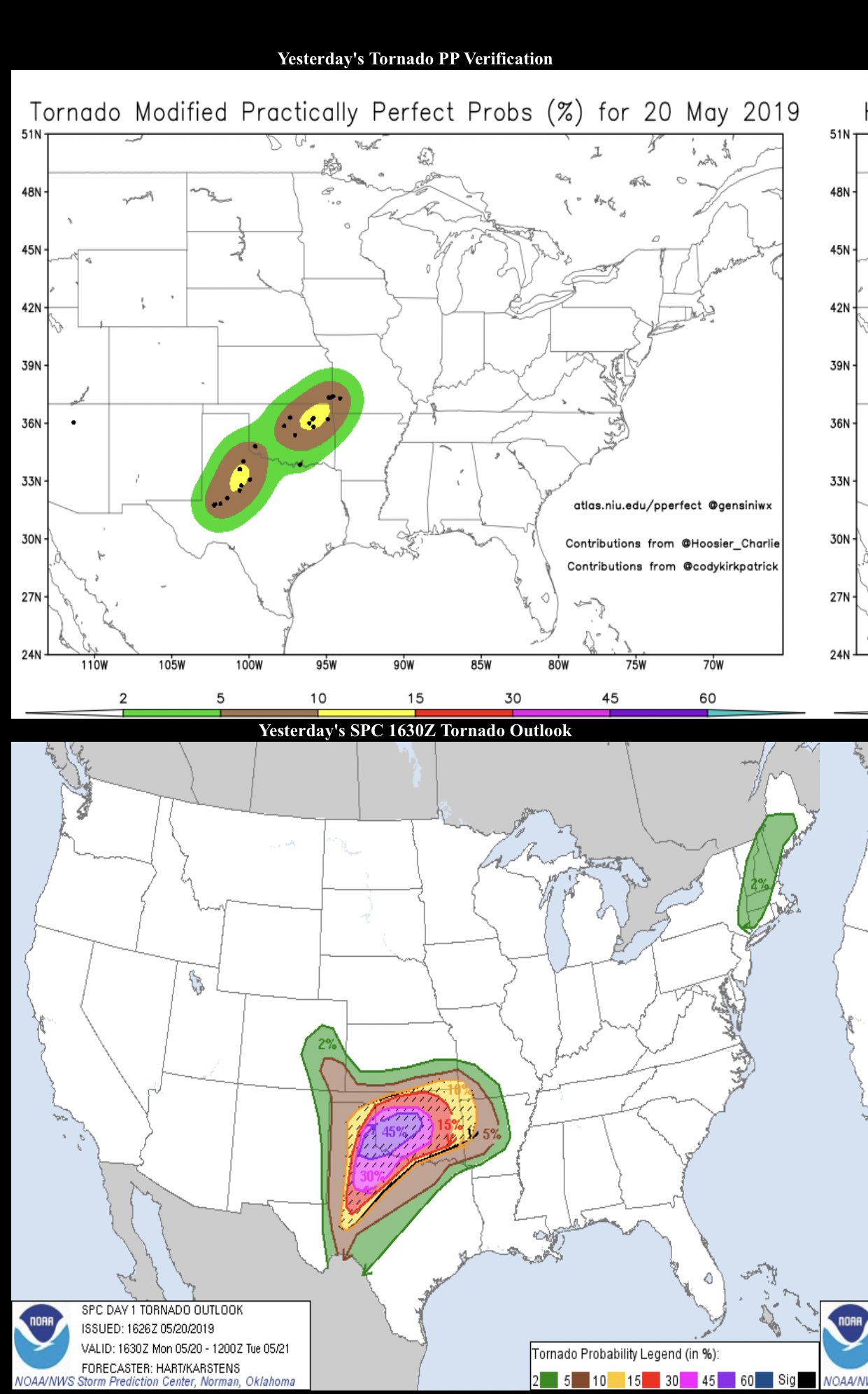

Removing subjectivity from the case, there certainly had not been the outbreak of long-track, violent tornadoes that forecasts had called for all day. 39 tornadoes were confirmed over the course of the period, with only four of them being significant tornadoes (two of them in the Midland-Odessa area, the EF-2 near Mangum, and a late-night EF-2 in northeast Oklahoma in the QLCS). Practically perfect hindcasts suggested that the day had performed at an enhanced risk level, rather below the 45% probability actually outlined.

And yet, there had been unanimity across the weather world that May 20 was going to be something special. The SPC is staffed by likely the best collection of mesoscale forecasters in the world. The TORUS project had assembled some of the most experienced tornado field researchers out there. Mesoscale models continue to become more and more accurate with each passing year. All of these forecasters had agreed that May 20 was going to be a big day. The day taught me that for all we do know about tornado forecasting, there is still so far to go, especially on days with high-end parameter spaces when the range of outcomes is so vast and includes such dire scenarios.

I’ve seen various theories floated around in the intervening year and a half to describe what caused the baffling failure of a widespread tornado outbreak on May 20. Perhaps it was the early-morning MCS, which through latent heat release increased tropospheric subsidence downstream later in the day. A subsidence inversion did sharpen later in the day, as an EML advected in from the southwest.

That helps explain why storm coverage was limited, but there was a supercell that produced a tornado near Paducah mid-afternoon, which promptly fizzled out and died. The same thing happened to the Mangum supercell after it produced a tornado. Did weak low-level lapse rates preclude the rapid ascent of moist inflow, particularly as the warm sector became crowded with little showers in the early afternoon?

Perhaps it was something that hadn’t been studied before. Another school of thought focused on the visibility-killing smoke plume in place, that had horribly mangled our chances of a closer deployment. Had that smoke also impacted the strength and longevity of supercell updrafts?

This theory would be bolstered two days later, when another pristine, PDS-watch environment fizzled out right over the OKC metro, with a supercell going up near Lawton before dying. In fact, one of my classmates would make it the subject of his capstone project the coming year. But if that was the case, why did a mile-wide wedge tornado develop near Canadian, Texas a day after that, so completely shrouded in smoke that it was impossible to see from anywhere outside of the bear’s cage?

I haven’t fully kept up with the science of why May 20, 2019 did not become one of *those* days. Perhaps the answer has become more clear with time than it was in the confused hours and days immediately afterwards. If so, I would love to read the paper and better understand. I think it’s important to couch my account my pointing out that I was still an undergrad when this occurred, and there are hundreds of mesoscale experts who know so much more about severe weather than me. But to me, this remains one of the most baffling severe weather events in history.

In reality, we had fulfilled the prophecy Cameron Nixon had foretold earlier in the day – a momentous day for tornado research science. Just not in a way anyone could have guessed.