There was a little bit of construction on the sidewalk, so I had to step into the road to get where I was going. It wouldn’t do to have to go the bathroom once the event had actually gotten underway. The sun shone down from a clear blue sky on the Ozark foothills, on the Arkansas River Valley, and on the north slope of the Ouachitas in the distance.

I sidestepped the construction on the way back to the car, sending a text to my family:

Partial eclipse begins in 5 minutes here.

As I made my way slowly back to Elizabeth, seated in our lawn chairs under a tree in the parking lot of the Johnson County Senior Activity Center, I had a quiet few minutes to reflect. This moment had been agonized over for hours, planned for days, anticipated for months, and waited on for years. The next 80 minutes or so would be a culmination – another of those “firsts” in our lives, which, when you reach your mid-20s, start to become more and more rare. All morning I’d wanted it to be right when it was now – 12:30, and the show just beginning. Now I thought of all those other times when it seemed like time just refused to move at normal speed. And I sent a quick prayer to God that now that we were here, maybe he’d let time slow down a little bit.

I reached the lawn chairs, where Elizabeth and Vivek were waiting for me to return. My phone buzzed. It was 12 hours, 32 minutes, and 58 seconds into April 8, 2024. The internet was already abuzz with tweets showing the shadow of the moon crossing the Pacific ocean and making landfall in Mexico.

This is my story of the 2024 Great American Eclipse.

“Partiality has arrived!” I announced. Elizabeth, Vivek and myself all raised our eclipse glasses to our faces and looked up at the sun. The novelty of doing something so basic, yet so taboo – looking at the sun – never ceases to tickle my funny bone, even if you’re using fancy glasses to make it happen. Unsurprisingly, it took more than mere seconds into the 2024 Eclipse for the moon’s obstruction of the sun to become visible. Idly, we speculated on what corner of the sun the moon would take its first bite out of. I plopped back in my lawn chair under a shady tree – no use getting sunburnt while waiting for sunlight to disappear. After a swig of Gatorade and a Sour Patch Kid, I remembered the envelope next to me.

To narrate the 2024 eclipse, we really have to go back to August 21, 2017. That was the first day of Elizabeth and my sophomore year at OU – and also the day of the first total solar eclipse in the United States in almost 40 years. The path of totality traveled through Nebraska and Missouri – easily within one day’s drive from Norman.

But it was also the semester I was taking Thermodynamics, Dynamics, Atmospheric Measurements, and Differential Equations, all of which met for class that day. So Elizabeth and I decided to be responsible students and attend classes. The morning of, all three meteorology classes canceled, because of course they did.

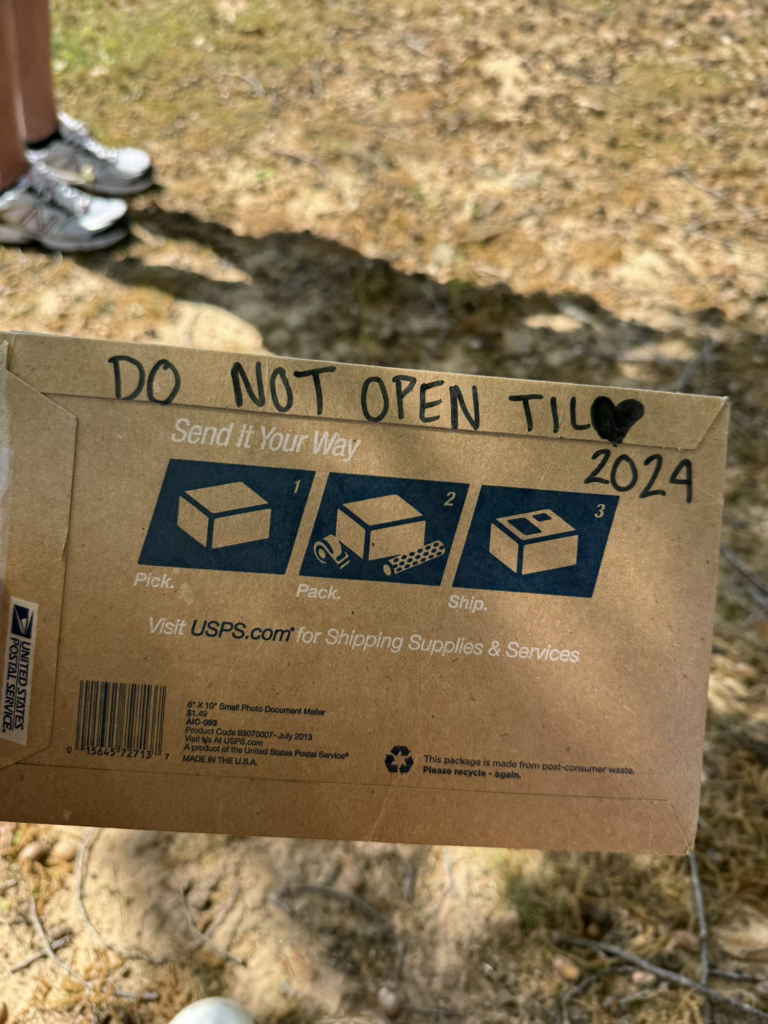

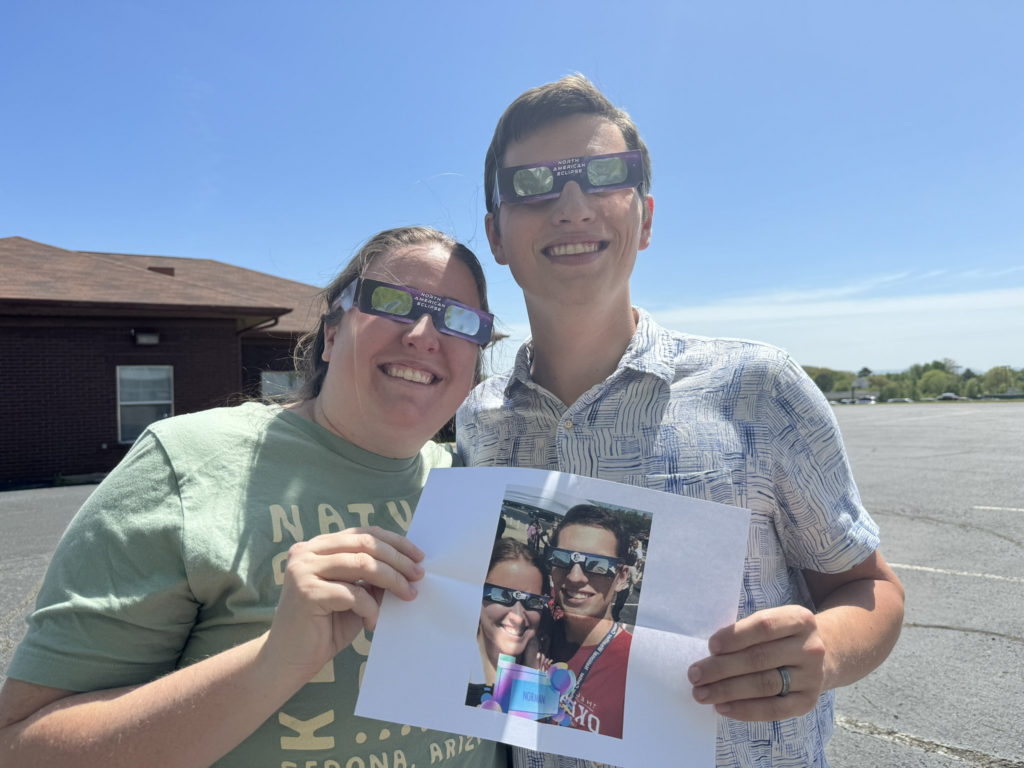

We vowed to visit totality for the next solar eclipse, which the Internet said would occur all the way in 2024. Elizabeth had the idea to write notes to each other, seal them in an envelope, and open them on the day of the 2024 eclipse. I scoffed – not because I didn’t think we (after only 8 months of dating) would still be together in 6 and a half years, but because I thought she’d never remember that this little time capsule even existed. But at her insistence, I sat down at my coffee table in James and my Traditions West Apartment and wrote her a note. She sealed them up and we headed off to the National Weather Center – but not before testing our our eclipse glasses and exclaiming at the chunk of the sun that was already covered up by the moon.

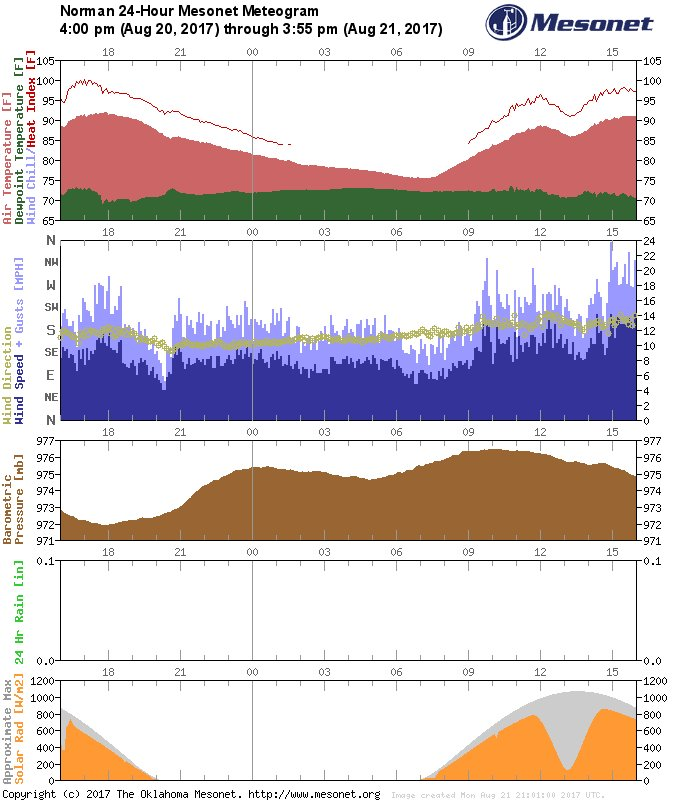

My employers at the Oklahoma Mesonet had set up a tent in the NWC parking lot to enjoy the eclipse for the 85% or so of totality we reached. It was pretty cool – literally. The maximum eclipse level reached was just enough to drop the temperature about 3-4 degrees…

…And to start seeing some really weird shadows under the trees…

…And for the light level to drop nearly imperceptibly, almost making my pictures look sepia-tinted.

All of this was really quite exciting – at least until my classmates who had traveled to totality arrived back in Norman. To a person, each of them swore what they had experienced was indescribably amazing, bordering on a spiritual event. To them, a partial eclipse was nothing compared to a total eclipse. It was totality or bust.

I was disappointed, of course, but you can’t miss what you don’t know. Elizabeth stowed away those notes for that eclipse way off a third of our lifetimes into the future. Just like the moon after the fourth contact point when an eclipse officially ends, life keeps marching on.

And life did keep marching on. Everyone forgot about the eclipse a week later when Hurricane Harvey made landfall in Texas. Then Baker Mayfield won a Heisman, Elizabeth discovered national parks and passed her calculus classes, we got paid to be storm chasers, a global pandemic halted the world, we graduated college, Joe Biden beat Donald Trump, I bought an engagement ring, then I defended a thesis, then I started my dream job with the NWS, then I got married. Pounds filled in my previous runner’s body. A few weeks ago, I noticed a gray hair in my front part – and then when I looked closer, I found another one right behind it. Elizabeth and I got a dog together – and if our bed was a total solar eclipse, he plays the moon every night by getting between Elizabeth and myself. She’s moved to 4 new places since that dorm room where she initially stored the notes, but each time the eclipse package managed to make it through the move unscathed. It marched on into the 2020s right with us.

While waiting for more of the sun to disappear from view, I suggested that we open the eclipse package from 2017. It was time to see the time capsule that Elizabeth had worked so hard to deliver to us on this day. First, she suggested that we hold it up for a picture together.

If you’re wondering why we were wearing sunglasses in the shade of our tree, the answer is that I had read to keep them on to keep our eyes adjusted to low light – it would make the final few moments around the beginning of totality even more magical.

I slipped a hand in the package – and was rewarded with not just two written notes, but two extra pairs of eclipse glasses (do eclipse glasses expire? We certainly weren’t willing to risk our retinas) and a printed picture of the two of us in 2017. *Now* we had our certified Photographable Moment.

Now that’s cute.

I read Elizabeth’s note aloud first. Here is the gist of it:

The year is now 2024 and hopefully we are opening this together… if not well then that’s awkward but I’m 99.9% sure I’m with you right now. You’re truely (sic) the love of my life and who knows where life has taken us over the years but as long as I have… (it continued on the back).

It was quintessential Elizabeth: heartfelt introspective, full of overthinking, and way longer than it needed to be – the letter version of a meeting that could have been an e-mail.

Then I read mine:

This is stupid and I’m like totality (ha, get it) sure that you won’t open this in 2024, but I love you more than anything so I did it anyway.

Quintessential Nolan – snarky to the end, but afraid to be too snarky so I got in trouble for it.

With that major life milestone out of the way, we could settle back into our seats. Elizabeth slipped her eclipse glasses on and exclaimed “There it is!” Sure enough, when I put mine on, a tiny chunk of the sun was bitten out of its bottom right corner. Our first eclipse effect had been noted.

I wondered if Phil and his family knew that we had gotten underway. I wandered over to their big old rental SUV. Phil was standing at the back.

“We’re officially underway!” I exclaimed. His parents, brother, and boyfriend all piled out of the car and put on their glasses. They began pointing and exclaiming, as all people seem to do when confronted by an eclipse. It was this denouement that seemed to bring them out of their collective shell, and they all eventually wandered up to our tree. I had had no plans to watch the eclipse with such an eclectic group (hanging out with work people outside of work!), but it was awesome seeing everyone having a good time.

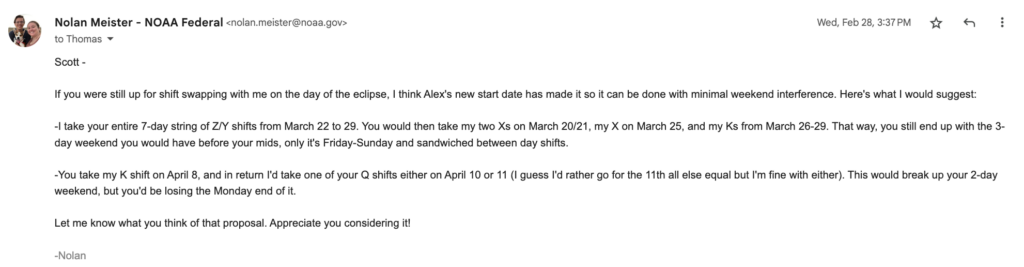

“The greatest leave crisis in NWS Norman history”. Vivek was already referring to the 2024 eclipse that way months in advance of its occurrence. As much as he has a flair for the dramatic, I don’t think he was wrong. Everyone knew that demand for annual leave was going to be at a premium – and in early April, a time of the year that the southern Plains are known for being rather active weather-wise. Speculation swirled around the office for months – how many people would management approve for leave that day? How many would make leave requests to begin with? Who would get priority? Some people were lucky and had that Monday off in the fixed schedule. Many more had extra (X) shifts that could easily be written off as long as it was a relatively quiet weather day. And some people, myself included, had operational shifts that someone else would have to cover if they wanted the day off.

Leave requests cannot be made at WFO Norman until 6 months before the day of the leave. At 12:01 am on October 8, 2023, Vivek made his leave request for the eclipse. A bunch of people followed suit immediately afterward. And somehow, it took me until a few days later in the (clouded-out) path of the annular eclipse in Oregon before I remembered I needed to do so. Oops. By now, I’d already lost the claim to primacy in my leave request. I’d never had the claim of seniority. There was a very real chance that Elizabeth and I were going to miss the Solar Eclipse of 2024 after all.

With the primary eclipse-leave strategy out the window, I went rogue, as they say. Once the planning schedule had been approved, it was easy to see those people who had gotten their AL requests in for April 8. It was easy to see who had agreed to cover shifts to fill in for them. And it was easy to see that almost 90% of our operational staff were either on leave or working that day. I’d have to work smarter, not harder, to figure this out, especially since I doubted Mark would approve yet another leave request at this juncture.

There was another option: a shift swap. A precious few people remained off that day with no plans to drive into the path of totality. Alex Zwink was one of them. He had an operational shift on Wednesday the 10th, which was an off day for me. So as long as he agreed – and he readily did – Alex could work my day shift on Monday the 8th, I could work his on Wednesday the 10th, we’d both still be working 40 hours. Maybe I was clever enough to work my way through this after all. Or maybe not – after months of rumors, interviews, and fighting the federal government’s hiring process, Alex accepted a position at WDTD. And it started in March. It was back to the drawing board.

By now I was desperate, and the schedule was ever-so-fluid when another forecaster got hired by the SPC with a start date of… April 8. Through the early months of 2024, the planning schedule remained in flux. I had pretty much written off the chance of going to the eclipse – but when the schedule got re-posted, there was one forecaster left who was not either on an operational shift or on leave that day – Scott. If I could just convince Scott to swap with me, I could open up April 8. Given the knowledge of market scarcity that awaited me, I opened with an offer that he couldn’t refuse:

In essence, if he was willing to break up a 2-day weekend, I would swap into a full string of midnight shifts on his behalf. Unsurprisingly, Scott agreed to the deal, and I duly showed up to work from March 22 to March 29 to work a string of midnight shifts. With every single one of them, there came a moment around 4:00 am when I’d look at the clock, sigh, and pray that there wouldn’t be any cloud cover on April 8.

We had just under an hour to go to the eclipse, and still the crowds weren’t bad. After the horror stories I’d heard from 2017, when people were stuck on the highways for hours getting back from the eclipse, Elizabeth and I had basically prepared for Solar Armageddon to descend on us. But the Clarksville Aquatic Center parking lot remained nearly empty, with just a few cars parked along its eastern fringe near ours. There was a Honda CRV at the Senior Activity Center on the other side that kept pulling in front of us, but then they’d do a U-turn and return to the backside of the parking lot. Otherwise, it was an incredible vista for such an unassuming spot. There was a nearly 180-degree line of sight in front of us, and you could easily across the Arkansas Valley to the Ouachitas in the distance. How were more people not swarming up to this?

Most welcome of all were the blue skies. I squinted at my phone, where the College of DuPage satellite viewer was looping. “Looks like there’s a band of cirrus coming out of southeast Oklahoma, but nothing that will mess up our viewing.” Deep sigh of relief.

It turns out that when you go eclipse chasing, it’s sort of the opposite of storm chasing. In storm chasing, you wishcast that band of cumulus clouds forward in time so that they become massive supercells in a fictitious future.With eclipse chasing, you’re looking for every reason for clouds not to exist. And not just any clouds – you learn to discriminate based on cloud height, sky coverage, optical thickness, the whole shebang.

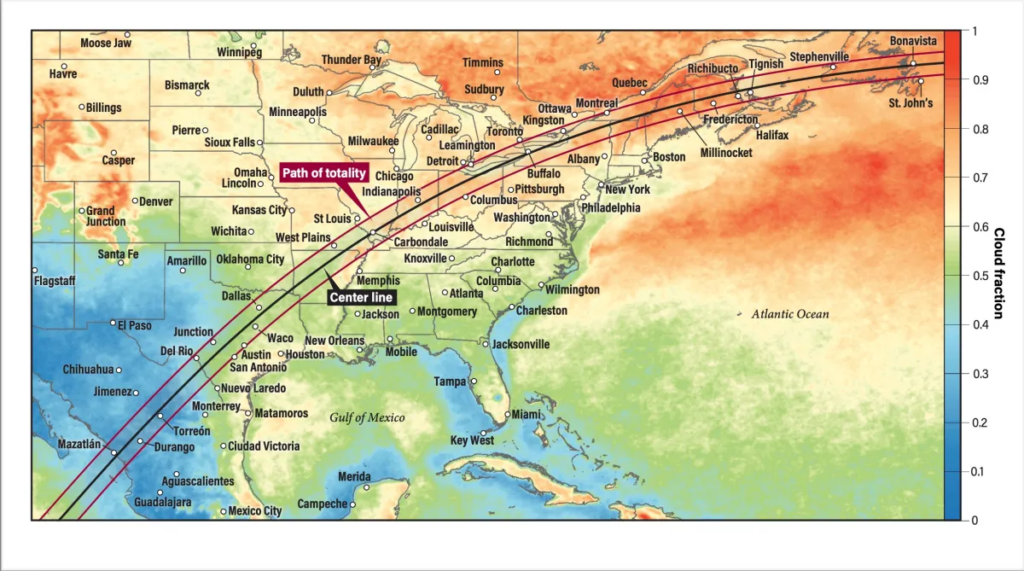

It may come as no surprise that early April is a climatological maximum for cloud cover on the southern Great Plains. That was always the fly in the ointment – Elizabeth and I could put together a great travel plan, only for a giant band of isentropic ascent to leave a block of stratus from Uvalde to Little Rock, and we’d be in trouble. We tried to play the odds and percentages. But a seasoned sports bettor like me knows that even if you play the percentages, weird things happen when your sample size is n=1.

The trick was to find a way to maximize our opportunities to adjust within the eclipse path while still being close enough to home for us to get into work the next day. On a normal day, it’s about 4 hours from Waco or Little Rock back to Norman. But April 8 would be no normal day, and I-35 and I-40 would likely be madhouses on the way back. So if we could position ourselves somewhere in between them, we could keep an early-morning drive down to 35 or up to 40 in play. Denison, Texas made for a logical hotel spot for April 7. And even better, the Hampton Inn there was still somehow bookable, fully refundable, and not horribly expensive even though were somewhere between months and years behind the early eclipse planners.

The most nerve-wracking part of the “cloud-planning” portion of eclipse preparation was probably somewhere around 10 days out, as I was finishing up my string of midnight shifts. By then the stakes had raised – I was sacrificing a whole week of getting to sleep in the same bed as my wife to go for this, and it would be pretty silly-feeling to get to the day of and not be able to see the eclipse. Furthermore, long-range forecasts were all in agreement that some sort of trough would likely impact the Southern Plains in a window centered around April 7-9. The trough was unwelcome for two reasons: first, because the large-scale lift it would promote would likely encourage thicker cloud cover along the southern part of the path of totality; and second, because the trough carried with it a risk of severe weather, which could cause staffing issues at the office and logistical nightmares for Elizabeth and me if we were stuck in eclipse traffic. And in fact, some of the early indications that came from global weather models were… well… brutal.

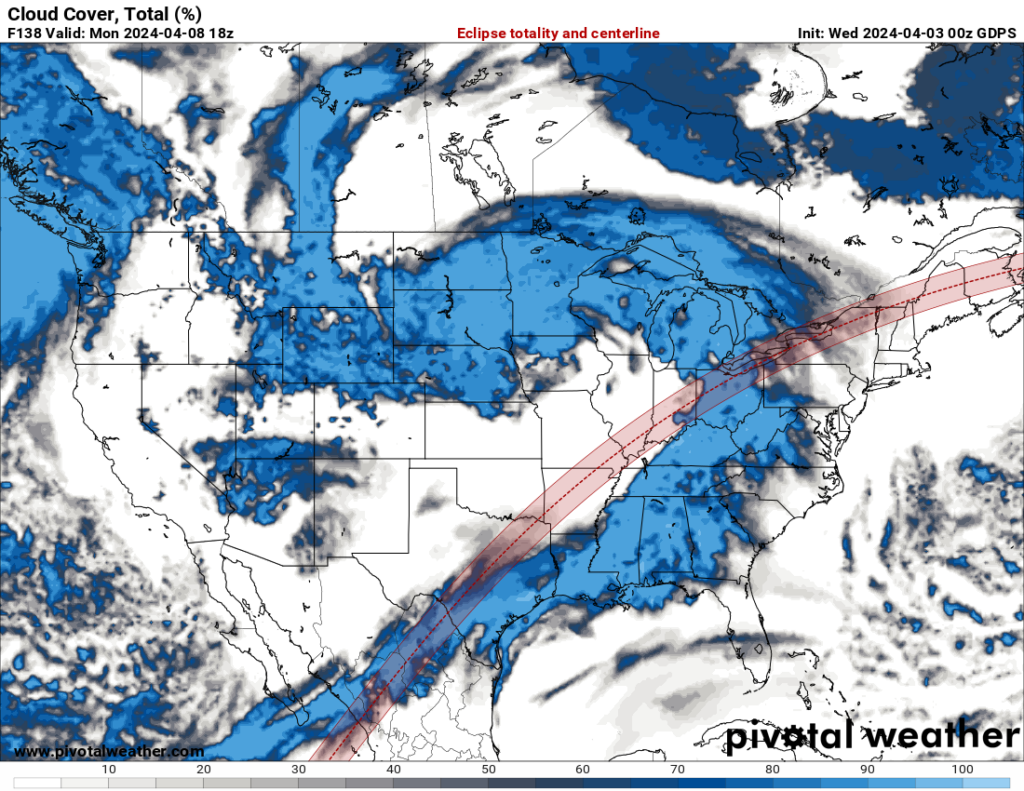

I’ll admit that I learned a lot about cloud forecasting because of this eclipse. Elizabeth probably took a more measured and healthier approach than I did – one of us was obsessing over forecast hour 264 GFS maps, and the other said she’d worried about it when it was time to worry about it. But one thing did start to become clear – the GFS is an absolutely horrible weather model for forecasting cloud cover. It was riddled with logical inconsistencies and seemed to just want to paint clouds with the heavy hand of Bob Ross after a few gin and tonics. I know a lot of storm chasers who also enjoy viewing the aurora, and they continually insisted that of all things, the Canadian forecast model was far superior to others when it came to cloud cover. I worked to overcome my initial skepticism in the idea while also retaining an abiding faith in overall synoptic meteorology, whether because I’m a pessimist who believes nothing that is too good to be true or because I’m just a stubborn old cuss. Fortunately, if the Canadian was right (and the synoptics seemed to lend credence to this belief), there was probably going to be a window of clearing behind a mid-latitude storm somewhere in the state of Arkansas.

That was the window: from somewhere east of Fort Smith up into Indianapolis (and, weirdly, Maine). The panic subsided for me – if there was clearing, we could drive out and meet it. But Texas especially continued to look pretty brutal with a lifting warm front and a signal for persistent stratus clouds. Elizabeth and I sat down on the evening of April 5 (with under 72 hours to go before the eclipse!) and looked at secondary hotel options for the 7th in Arkansas. Fort Smith was $350, Clarksville was even more, but the Hampton Inn in Fayetteville was just $175 for one night. That was reasonable, although the number of east-leading options out of town and into the path of totality within the Boston Mountains were limited. Still, I was at the point that I’d much rather start our day in Fayetteville than Denison. On the evening of April 6, after a whole lot of waffling, Elizabeth and I made the decision to pull the trigger and cancel our Texas hotel. I heard from coworkers who were making the same decision. It looked like we’d all be heading to Oklahoma’s eastern neighbor, where the Canadian model continued to loudly insist on clearing skies.

The fate of our eclipse lay in the hands of the state of Arkansas.

Elizabeth and I didn’t leave Norman until late in the afternoon on April 7 after I’d finished my day shift at work. Our limited staffing was running up against the feared scenario of a severe weather threat on the evening of April 8, and staffing concerns continued until Mark announced that he had canceled his leave and would remain in Norman to help out with weather (note: the severe threat actually delayed itself until late that evening, and I ended up going in several hours early on the morning of April 9 to relieve the evening shifts and help out with severe weather, so I don’t have to feel too guilty about it). I had a rough itinerary set up for Elizabeth and my next 24 hours (I learned from our honeymoon: NEVER vacation with Elizabeth unless you know exactly what you’re going to be doing at all times). The first stop was to drop Scipio off for his two nights at Fetch and Stay, then a quick trip to the Chipotle in Moore to stoke the fires.

And then we took off into the departing twilight, heading east on I-40 to make the three and a half hour drive into Fayetteville. I was curious to see the condition of traffic on this major east-west artery into the path of totality. And to be honest… it wasn’t anything more than normal. Sure, there were a few more RVs than one usually sees on I-40 in Oklahoma, but traffic certainly wasn’t heavier than normal, and I never got the sense that people at rest stops were all eager-beaver eclipse chasers getting into position the night before.

Elizabeth drove the rest of the way from Webber’s Falls to Fayetteville, which gave me plenty of time to read up on the origin of the name of Fort Smith and the fight against white-nose syndrome in bats along the way (very fun subjects!). We arrived well after dark, but not too late that we couldn’t make a dessert stop at Andy’s Custard before bedtime.

The Hampton Inn in Fayetteville was not quite a zoo, but you could sure see a zoo from the front desk. There were several groups all waiting to get checked in on a benign Sunday night in April while the harried front-desk worker tried to get through each group as fast as possible. When you put that scene in context with the map of eclipse totality hanging on the wall next to the front desk, it started to feel a little more like the eclipse chase that I’d been assuming we would experience.

I got a great night of sleep in our 57-degree hotel room (seriously, the room was set to 57 when we walked in) and was feeling much-refreshed when my alarm went off at 6:30 the next morning. A quick glance at the horizon said there was some high cloud cover cover, but soon the sun came rising over the Ozarks to the east and it was clear that it was going to be a beautiful April morning.

Somewhere in the sky sat the moon, all-but-invisible in its new moon shroud against the pale blue morning sky. The sun shone against the horizon, quickly becoming too bright to look at. Imperceptibly, the two began their dance toward each other. We were 6 hours away from nature’s greatest show.

We were now under an hour away from nature’s greatest show, and not much had changed. Phil’s family was now up at our waiting spot, and every minute or so someone would stick their glasses to their faces and exclaim at the new percentage of sun that had been blacked out. But if anyone tells you that the first half of a solar eclipse is dramatic, they’re lying to you.

I kept my sunglasses on as much as possible to prevent my eyes from acclimating to higher light amounts. Elizabeth did the same – until her sunglasses broke, at which point she had to return to her car for a second pair. The shadows, which had been so interesting in 2017, hadn’t really changed a whole lot under our tree. Maybe the leaves were too small and too young to really notice the effect? If so, that would be disappointing. I’d spent a good chunk of the last 6 hours reading up and preparing for some of the cool things to observe during an eclipse beyond just “here’s the corona”.

Speaking of… the SET app buzzed on my phone. At 40 minutes to go, it was giving me my first notification of something to notice. “Observe ambient temperature”. I paused. Maybe it was a bit cooler?

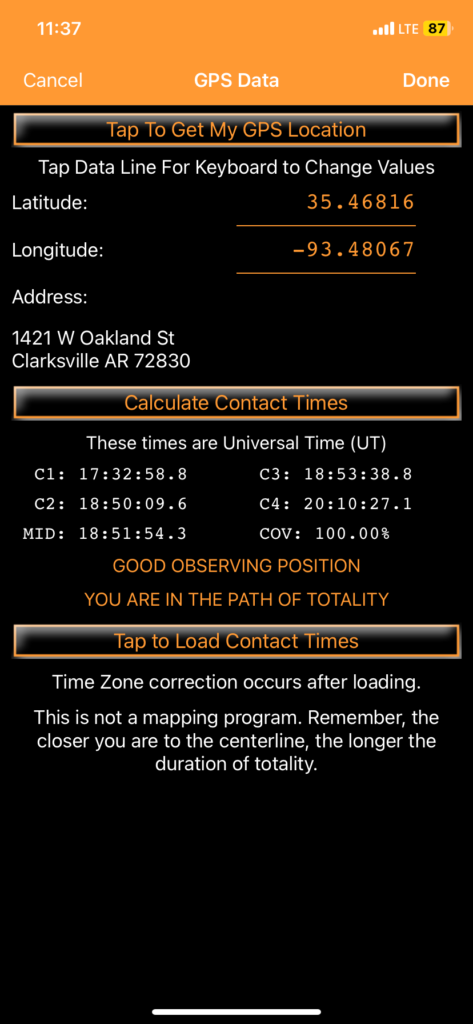

“There’s an app!” I exclaimed joyfully from the passenger seat. “It only costs $1.99, which is way better than it being a free app.”

I stand by that position. If you’re going to download the Solar Eclipse Timer (SET) app, then it damn well better cost 2 bucks. That way, you can tell people all about the handy use you got out of an app that cost less than half as much as Elizabeth’s Starbucks latte did that morning. And that’s way cooler than saying an app was free. If you don’t understand the difference, then you and I are fundamentally different people.

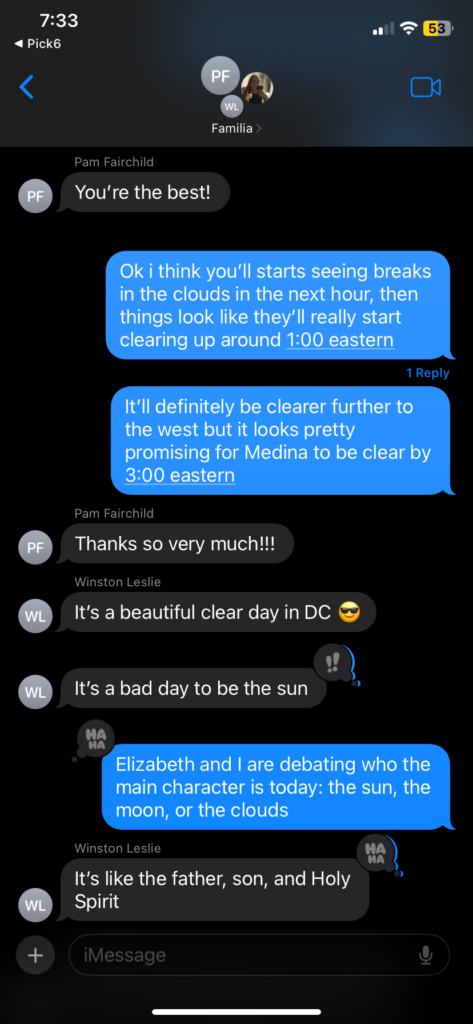

This joyful discovery had been made along I-49 southbound from Fayetteville. After much discussion, we’d decided not to make the daring eastward plunge out of Fayetteville into the heart of the Ozarks. Rather, we’d get up early and load up on Hampton Inn waffles (the batter of the day was red velvet!) and Starbucks coffee, then gas up her car and head back south to I-40. There was an unspoken hope there that I-40 hadn’t become too much of a madhouse, but so far I-49 traffic was extremely light. Along the way, I messaged with Elizabeth’s mother, who was visiting her friend in Medina, Ohio in the path of totality. I shared the app with her and provided a forecast since they were socked in by mid-level clouds at that point.

To my relief, I-40 was also clear. Elizabeth and I rolled into the path of totality a little before 9:00 am and pulled off at a Love’s Travel Stop in Clarksville, Arkansas. The big draw of the Love’s? It holds the nearest Bojangles to Oklahoma, and the Meisters are definitively a Bojangles family. Our options were to wait at the Love’s for a while, grab an early Bojangles lunch, then hunt down our spot, or to go look for somewhere a little more peaceful to hunt down our viewing spot to begin with. The Love’s was not anywhere near as overrun as I feared (it was nothing compared to a poor Love’s on the Great Plains when the TORUS project rolled through), but it was certainly busier than a normal 9:00 am on a Monday morning in April. We both agreed that it might be nicer to wait some of this craziness out at the city park and then come back in an hour. So we took some town roads and ended up at the town baseball field a mile away. The gate was open – a perfect place to set up for an eclipse, when you think about it.

No sooner had we settled in than my coworker Vivek texted me to tell me he had just arrived in Clarksville. Rather than paying the $175 for a hotel room, Vivek had canceled his booking out in San Angelo and had decided to just chance a drive down I-40 the morning of. The fact that he got into town 15 minutes behind us says maybe we didn’t need to spend money on the hotel; the fact that he left at 5:30 and I have 7 and a half years of experience with Elizabeth tells me that it was the best money I spent all week. Vivek was looking to meet up with us at the Love’s. I shrugged: we were heading back there in a bit for lunch anyway, so what the hell, why not?

Oftentimes, I am accused of being “too happy”. I don’t think such a thing really exists, but to each their own. But even I am aware that when certain things are beginning – the first drive into a national park, kickoff on a long college football Saturday, the first glimpse of an updraft while storm chasing – I get downright giddy. And to put it bluntly, I was feeling giddy by about 9:30 when I called out “Dr. Mahale” and shook Vivek’s hand alongside the northwest corner of the Love’s store. Elizabeth certainly hadn’t helped my childlike excitement by buying me a green Gatorade and a bag of exclusively blue Sour Patch Kids as well.

We greeted Vivek and leaned up against the side of the Love’s, chatting and watching the madhouse slowly fill in. People were setting up lawn chairs out in the grass next to the parking lot. People were setting up tents down the parking lot a ways. Some harried-looking employees of the gas station walked from setup to setup, explaining whatever rules they had in place. I pulled out my eclipse glasses for the first time and cautiously stared at the sun. The first glance was like a time machine back to that 2017 eclipse – all of a sudden, I remembered standing outside my apartment at Tradition’s West right after writing our notes, putting the glasses up to my eyes, and seeing that all-black field of view with nothing but an orange circle inside of it. Who knew an eclipse could cause nostalgia?

By a funny coincidence, Vivek and I weren’t the only NWS Norman employees who were planning to make a stop at this Love’s. Phil Ware was on the way east from Norman with a rental car full of his parents, his brother, and his boyfriend. They got a later start than Vivek and were apparently dealing with some of the nascent eclipse traffic, but would be here soon. It was sort of offensive that I-40 was even passable, but whatever.

By around 10:00 I was already getting antsy. It was just like getting to a target early while storm chasing – you psyche yourself out, you can jump too early on the wrong storm, you feel like you have to move. It was equally ridiculous to feel this way in an 80-mile-wide path of totality, but that’s how it felt. What if the Bojangles line completely wrapped back into the Love’s parking lot by the time we were actually hungry? Elizabeth continued to insist she wasn’t ready for lunch (which is a totally fair and normal thing to say at 9:30 am), but finally by 10:00 she relented. It’s a lot easier to trick yourself into eating early when it’s the best dang fast food chicken on the market.

The seasoned fries. The biscuit. The Bo’s sauce (it’s just horseradish and Thousand Island). The chicken. Mmmm. Delicious – even if Certified Health Food Nut Vivek may not have agreed as enthusiastically.

Phil and Manuel walked in right as the three of us were finishing up their food. Phil’s family did not, which either spoke to a group of people who were exhausted from flying out from Virginia to OKC and driving 4 hours, or spoke to a general weariness with Bojangles. Either way, we were well on our way to a regular old NWS Norman reunion when – what else? – our Science and Operations Officer, Todd, gave me a call. He too was out to find the eclipse, and he too had abandoned Texas in favor of Arkansas in the final few days of eclipse planning. And unlike me, who was already taking a victory lap over the beautiful sunny morning, Todd had his eye on satellite.

Over in Russellville, 25 miles to our southeast and deeper in the path of totality, Todd was watching a band of stratus as it migrated north and east from Texas into southeast Oklahoma and southwest Arkansas. I pulled out my phone and loaded in the College of DuPage satellite page. Swiping back and forth on the slider, I squinted and muttered and tried to extrapolate the pace of the cloud cover. The answer was unsettling. If clouds were moving about 1 county per hour, and we were 3 hours from totality, and the leading edge was 3 counties away… the math mathed up to a stressful few hours.

Opinions were divided. My preferred bailout was to a spot called Haw Creek Falls, a waterfall 25 miles northeast of Clarksville. If we left pretty rapidly, we still had a decent buffer to get there before the partial eclipse began. However, it had to be a full-send maneuver – who knew if there was cell service way out in the sticks like that. Todd was nearly committed to leaving the line of I-40 to head from Russellville to Marshall. I wouldn’t have minded the extra buffer space myself. But Phil pointed out that the stratus advance was likely to slow up as the moisture that fueled it left the Red River Valley and ran into the Ouachitas. Besides, he had family with him and didn’t want to relocate. Vivek didn’t want to go far from I-40 because he was hoping to get home early and potentially work the overnight severe event. Elizabeth and I certainly weren’t bound by their decisions; we could go off on her own. But Elizabeth viewed the Ozarks and their potential shotgun-toting inhabitants with distrust, and wanted to stay in town.

Meanwhile, the discussion of stratus and moisture pooling and warm fronts had drawn the attention of folks at the Love’s. Now it felt more like being on TORUS than ever – or like being a storm chaser, only you’re the one who actually knows how to forecast that everyone else is secretly just following around. Giddiness was replaced by a feeling of claustrophobia; our time at the gas station had come to a close in my book. Vivek agreed to follow Elizabeth and myself out of the Love’s and back toward the city park, thus sealing in who we would be spending totality with. This time we took a different path through town, and our route to the city park and baseball field was cut off by a construction fence in front of the Clarksville city aquatic center. Recovering some aplomb, Elizabeth and I agreed that the backside of the aquatic center parking lot would do just as well. In fact, it would do great; there were only a few widely-spaced cars on the east side of the lot, and a grand total of zero in the parking lot for the Senior Activity Center, which was raised another 6 feet higher and had our soon-beloved tree to boot.

By a little after 11:15, Elizabeth and I had our lawn chairs set up under the tree and I was pacing in nervous anticipation. There was no sign of stratus on the horizon and the partial eclipse began in a little over an hour. I took a look at the satellite loop again. Just as Phil had predicted: the cloud cover hit the Ouachitas and stopped like it had hit a damn brick wall. Meanwhile, the sun was shining in Medina just like I’d promised Pam. Even off-duty, NWS Norman employees were shining today.

There had been a lot of steps to get here. Every timescale had its story: the last few hours, the last few days, the last few weeks, the last few months, even scaled out to the last few years. And all of that planning, heartache, and logistical work came so that we could experience something that would last for a grand total of (according to my $1.99 SET app) 3 minutes and 29 seconds in our parking lot.

Is it any wonder that I was pondering the speed and passage of time when I wandered over to use the bathroom at the start of this post?

Ok, I promise this is the last jump in time. And I promise if you’ve hung in there for the (now 6,000 words and counting) torturously drawn-out prose and philosophy interwoven with mundane details about Sour Path Kids – this is your reward. This next section outlines the last half an hour leading up to and into totality.

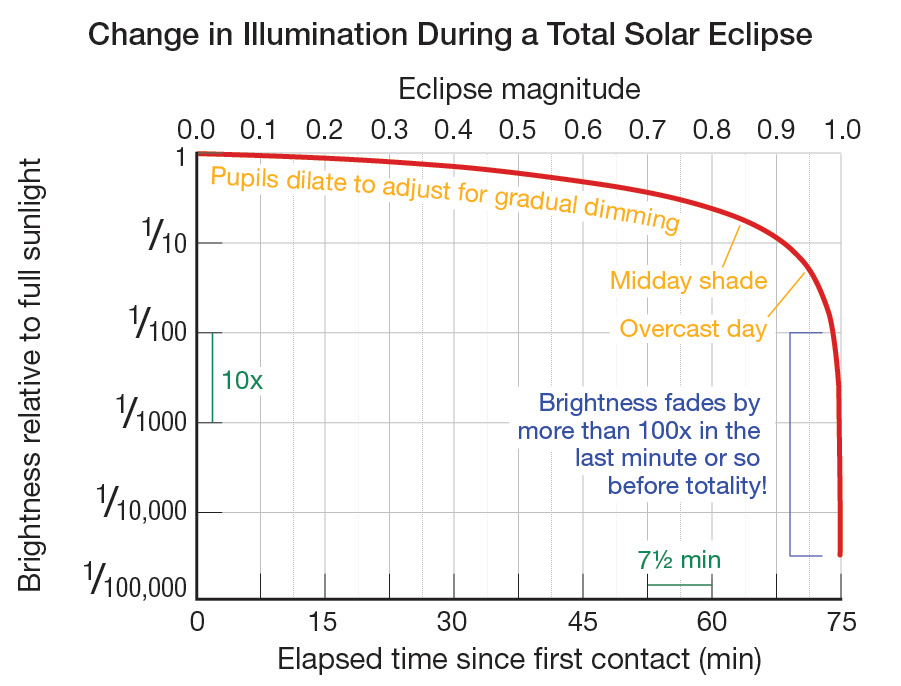

Anyone who tells you that they noticed a difference in light during the first 45 minutes or so of the 2024 Eclipse is a liar. I have a graphic to prove it.

We’d lost maybe 5% of the sun’s illumination. It was maybe just enough to notice that the day was cooler, and there certainly was a big chunk bitten out of the sun with the eclipse glasses on. But no, you otherwise couldn’t tell.

My SET app told me to observe the “pinhole” effect. From what I’d read from others, this is best found by taking an object such as a colander and tilting it toward the sun. When you do, the crescent-shaped pattern of the sunlight shows on the other side of the colander. We didn’t have anything like that, and would have to watch leaves to see. Everyone stared at the shadows beneath our tree. There wasn’t a whole lot to see at 1:10, and you hate to be the person who just makes something up for the sake of making something up. Phil’s mother in particular was rather unimpressed.

But when we looked back a few minutes later, Elizabeth was the one to notice. If instead of looking at the shadows, you looked at the spots of sun, there really was a crescent pattern going on. At 1:20, with 30 minutes to go before totality:

And then you didn’t even need to wait for the flutter of the leaves to see it. By 1:30, we were fully into the crescent-shaped funniness.

This I think coincides with the picture I took in 2017 from Norman? I remember that in 2017 I thought the lighting had dimmed a small but perceptible amount. It was starting to feel that way here, too. The day wasn’t necessarily super windy but there had been a little breeze as the sun rose higher in the sky. Now that breeze began to die down. The weather wasn’t necessarily noticeably cooler, but the air did seem to hang a little heavier.

Elizabeth and Vivek plotted their filming strategies for totality now that it was mere minutes away. Vivek walked around the Activity Center building to set his phone up on a dumpster to take a timelapse with. Elizabeth planned on taking pictures with her iPhone, but I staunchly refused to do anything other than take in the moment. So she co-opted my phone to take a “reaction” video from behind with and started setting it up against a chair so you could see the three of us (with Phil and his family just to the left of the camera’s field of vision).

Meanwhile, I made one last look at satellite and couldn’t believe how well things were coming together along the entire path of totality. Unless you went all in on seeing the eclipse from Niagara Falls or you were in central Texas, things looked amazing. I’d worried all morning about Sam, who drove down on his own to McCurtain County. That stratus band had settled over him, but slowly degraded into billow clouds, and now things were dissipating right over him. Further south, I was unaware that James was visiting his grandmother right on the edge of the totality path. He remained just barely shrouded in cloud cover until after the moment of totality, but texted us at 1:42 that he “couldn’t believe how dark it got”. Up in Ohio, Pam was under clear skies with her friends. And most importantly, here in Arkansas, Phil’s instinct had won. There was a streamer of cirrus floating in last second, but it could never possibly be enough to shroud the sun-moon show that was approaching its last act. Further to the northeast in Marshall, Todd wouldn’t even have to worry about that – his late duck out of Russellville had given him clear skies. Yup, just about everyone was winning.

The last few minutes before totality were absolutely wild. I hope they remain etched in my brain forever. The one thing I didn’t check for was the presence of an illusive phenomenon called “shadow bands”. These bands are basically impossible to describe, but it’s basically where shadows flicker on and off on the ground right ahead of totality. The all-black surface of the parking lot would have been perfect, but in all of the excitement I totally forgot to look for them.

But there were some incredible things to look at. First of all, there was the sun, reduced by now to just a tiny sliver in the bottom left corner by the intrusive presence of the moon. Animals, too, were acting funny – when you took a moment to pay attention, birds were chirping like it was the evening. I watched a crow try to take flight, realize that its normal midday thermals weren’t there, and then alight in a tree for the rest of totality. Then, as Elizabeth and I removed our sunglasses for the first time in hours, it really was not 2:00 pm daylight out here. It’s weird and not at all easy to describe, but the way Elizabeth and I pointed it out to each other was “It feels like the start of a horror movie”. The absolute stillness of the air didn’t help. You could just imagine Bill Paxton standing us on this hill with us, looking into a sky that was fading to a bluish-white, and waiting for the tornado to come out of the distance. But it wasn’t a horror movie. I was 99% sure of it.

Off in the southern distance, the horizon just above the Ouachitas started to glow a very faint orange. Now it was pretty clear that twilight was settling in. An eerie silence descended. It took me until after totality to realize what made the quiet as unsettling as it was; it was the complete lack of traffic on I-40. All morning we’d heard the classic human rattle of cars from a mile away. Now, there was none. And then the light leaked out of the day.

Elizabeth’s video from my phone is great here, because it preserves all of our actions and words from the next four minutes or so. Totality is an overwhelming experience. It’s nice to have the record.

Elizabeth squealed: “It’s so weird!”

“Don’t look up quite yet,” I admonished. (Please note: Elizabeth is smart enough to not look up on her own).

Manuel made a fake countdown from somewhere behind. I looked over to see if he knew something I didn’t, then immediately returned to my hands-on-hips dad post, looking at the deepening twilight.

About 30 seconds later, as twilight continued to deepen, the noise from other groups in the parking lot began to crescendo. “Is it safe?” I wondered, looking around. No way was I wasting these last few seconds and putting my eclipse glasses back on. You could literally watch the darkness deepening. Elizabeth replied: “I want to look up sooooo bad.”

And then the crescendo grew to a roar. “WHOOOA”. “Oh, shit”. It must be safe the way everyone was reacting. In just the last 30 seconds alone, we’d gone from horror movie lighting that felt like an “Approaching rainstorm” (Vivek’s words) to something that very closely resembled nighttime. I’m not sure I’d ever experience something like it again.

And then I looked up, and everything I’d experienced until then seemed insignificant.

I was staggered. And I mean literally staggered. You can see it in the video – my knees literally buckled at the sight of a total solar eclipse hanging over the Arkansas sky. I pride myself on being a talented if sometimes verbose writer, but there are truly no words to describe a total solar eclipse. The really zoomed-in pictures, of which there were a ton of absolutely stunning examples on social media in the coming days, that show the zoomed-in corona? Those do not do the actual thing justice. For one thing, the sky isn’t totally black. Instead, it’s a deep twilight that feels like nothing so much as a campfire sky. Twilight extends 360 full degrees around, and that’s insane in and of its own right. But the star of the show is the one area where the sky is totally black – the disk of the moon, outlined by corona of the sun. Later on, when Elizabeth and I were struggling to find descriptors for it, the best I could come up with was “the brightest white you could ever imagine, with an absence of color in its middle.” Right now, all I was coming out with was “Oh, my god” in reverent tones. Absurdly, I remember thinking that I could totally understand if a solar eclipse caused a major religion to form. For 3 minutes and 29 seconds, it was safe to stare at this apparition. Of all of the images I’ve seen from totality, here is one of the few that really made it look the way that it did in reality.

And even then the corona was somehow brighter and narrower than what this shows.

I looked all around me. “It’s… nighttime!” I exclaimed. Which it most certainly was. The lights had come on at the nearby baseball stadium. Anyone who says the stars come out during an eclipse is a damn liar, but Venus was visible to the naked eye. It was so bright, in fact, that Venus showed up in Elizabeth’s picture.

It was around now that my contacts failed me. One eye or the other, I don’t know. Twilight has always been the hardest for me to focus during because of the extra straining you do, and my vision started to go blurry. I don’t want to complain too much because it was still an otherworldly thing to live through, but maybe I’ll get Lasik before my next totality. It wasn’t so bad that I couldn’t see one of the most truly incredible parts of totality: a bright red spot at the bottom of the corona that marked a solar prominence, which showed up after a minute. Another one could be seen near the end on the right side. Some of the eclipse photography that got them was pretty incredible.

The other unsettling part of totality was the lack of knowledge of when it would end. 3 minutes and 29 seconds can seem like it goes by in the blink of an eye, or it can seem to stretch on forever. When you’re worried that at any given moment the sun will pop back out and roast your eyeballs permanently, it is cause for pause. Next time I will absolutely bring a stopwatch so that whoever I’m with will be comfortable knowing exactly when totality ends. This time, it was funny to watch the video. I’d tentatively peak up at the corona, because WOW, but then I’d look away a few seconds later because PLEASE NOT THE EYEBALLS. And I wasn’t the only one: Elizabeth kept asking when it was going to end, when it was going to end. A lot of people afterwards said that totality was the shortest 4 minutes of their lives, but for me it seemed to drag on forever. For Vivek, who’d been in the path of the shorter 2017 total eclipse, this one was also noticeably longer.

Just as I’d settled into a rhythm of peering up at the corona and then turning to the much-more-comfortable-to-look-at-and-still-awe-inspiring 360 degree twilight, the sky really did brighten. One of Phil’s family members yelled “Here it comes!” And then there was bright flash of light on the right side of the corona that I can literally only describe as “God descending to Earth”. Photographers from around the U.S. went for the killshot – the diamond ring effect as the run returned.

And here in our parking lot in Clarksville Arkansas, the sun came back out. The Great Solar Eclipse of 2024 was over here, though I could still see the darkened twilight in the northeastern sky. People in the parking lot behind us applauded like they were on a Southwest flight that had just landed in a light rain shower. I didn’t applaud, but I sort of got it. For the next 5 minutes, we all continued to speak in the hushed tones that seemed appropriate for a moment like this.

Elizabeth’s immediate verdict: “That was insane. It was like something not in this world.” I’ve heard that cliche before, and it usually fits pretty well. She trotted it out at Norris Geyser Basin in Yellowstone and like 16 times in Iceland, and she was absolutely right. But this was even more otherworldly than those.

Everyone spent the next few minutes looking through their pictures, which may be an indictment on the culture of humans in 2024. And before you think I’m taking the moral high ground, I’m not.

Originally I’d been warned to expect standstill traffic for hours. With that in mind, Elizabeth and I each had lawn chairs and books and no real plans to be anywhere for the rest of the evening. But so far, the traffic thing had been a gigantic scam, so maybe we should just leave immediately like Vivek was planning on doing. First I made a trip over to the Aquatic Center to use the (mercifully open) bathroom and blink my contacts back into place. I had the same thought about the relativity of time that I’d had when going to the bathroom right before the eclipse started. The eclipse had finished 15 minutes ago and it would never be this close in the rear-view mirror again. I’ve had that thought several times since then over the last two weeks of blogging, and each time it makes me a little sad.

Traffic on I-40 was heavy, but it was moving. I sort of figured that us being on the western side of the path of totality helped, as did our close proximity to the highway. If it stayed like this, we would be back potentially before sunset.

Well… things didn’t work out perfectly. There was construction going on around Vian, Oklahoma on the Interstate. Someone had a brilliant idea that they shouldn’t work on the day of the eclipse (smart!), but that they didn’t need to remove the cones from the closed lane that had nothing wrong with it (Oklahoma!). That made for slow going for an hour or so before we broke the bottleneck. Unsurprisingly, the first rest stop after the construction was… busy.

In spite of our snacks, Elizabeth was a little hangry by the time she finally drove into Shawnee around 6:30. That dictated her decision to call the shot for us to go to Tapatio Mexican restaurant in town. It turned out to be good, if not spectacular, and brought back the high spirits we’d had all morning and for the immediate first hour after totality.

On the way out from Shawnee, with Elizabeth finally trusting me to drive in the reduced traffic, we got a chance to talk to Pam about her eclipse experience. She seemed happy but not overwhelmed or awed – two words that Elizabeth and I had been using a LOT that afternoon. Presently, the explanation came out as to why. Apparently at some point during the partial eclipse, a man had said that you weren’t supposed to take your eclipse glasses off, even during totality. Pam and one of her friends had listened, and yet somehow her other friend hadn’t. So they’d seen the entire thing become a sliver and (maybe) seen the twilight, but if Pam was looking at totality through eclipse glasses all she would see is… darkness. That’s a pretty tough break for her, but the good news is thanks to her and her friend realizing that they’d missed the best part, I now know that during the next total eclipse there is a Mediterranean Cruise through totality for just $10,000 a person.

Elizabeth and I made it home not long after the sun had set. Again, I felt more than the usual amount of sadness watching the last light leave the day. Nature’s absolute greatest show had played out on a stage the size of heaven itself on April 8, 2024. That kind of show is something you may only see once in your life – and that’s if you’re extraordinarily lucky like we were. When would we ever see anything that grand again? Would we ever see anything that grand again?

I’m here on my final day of writing what had become by far the longest blog post of my life. It’s taken 2 full weeks to write, which means it’s been 2 weeks and 1 day since the Great American Eclipse of 2024. Many of those same words that I used in Elizabeth’s video – namely the “Oh my God” repeatedly – still apply when I think of the eclipse. There was just so much to it – the will-we-make-it-there drama, the will-we-see-it drama, the build-up – but it all pales in comparison to witnessing totality. I hope this blog has conveyed even a fraction of the wonder I experienced. I doubt it has. Will we ever see something like it again? Probably. It seems like once you get the eclipse bug, it doesn’t quit you. See Vivek and Todd going as far afield as they could to repeat the magic of 2017. The next eclipse to cross the Southern Plains isn’t until August 12, 2045. Elizabeth and I will get to take our kids, who will be old enough to remember it. That’s a crazy thought.

If there’s one final thing I can impart, it’s a plea. If you missed the 2024 eclipse, sit down and write a note to someone special. Make it sappy, make it silly, make it whatever. Find a total solar eclipse (they’re very easy to predict!). And go out there and experience something like you’ve never experienced before.