On April 8, 2024, Elizabeth and I fulfilled one of our great life’s goals: to see a total solar eclipse. It was moving on a deep spiritual level; you can read all about it here. In that post, I mused a bit about how we’re approaching a point in our lives where we’re starting to run out of “first _____”.

That’s not to say that none are left. We’ve spent much of the intervening time since the eclipse working toward buying our first home; hopefully we’ll have a decision made very, very soon and I’ll be writing our “Yay homeowners!” blog post. But in terms of first experiences, there’s a whole raft of national parks we need to visit and then… there’s the aurora borealis.

The northern lights. Despite my upbringing in Michigan, I had rarely if ever gotten the chance to see them. The last solar maximum occurred when I was super young and my parents had more important things to do than try to find them for us, and Michigan is far enough south to make the auroras kind of a rare occurrence anyway. But as we start to trundle into the next solar maximum later this year, my interest has been piqued. Many people call the northern lights a spiritual experience on par with an eclipse. The big difference, of course, is we know exactly when and where the next eclipse will be. You might get lucky and get clouded out, but you have years and years of warning. On the other hand, a giant geomagnetic storm might be a little more common, but you might only get 24 hours notice.

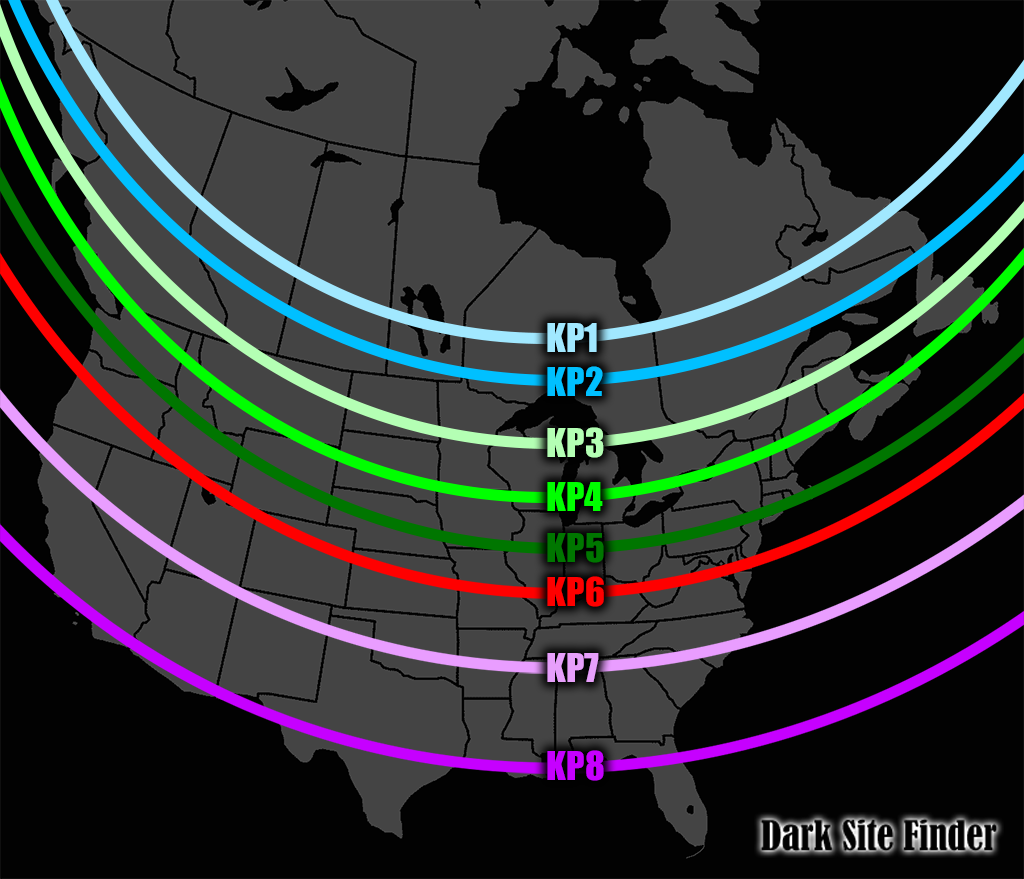

In 2023, I tried my luck as an aurora chaser for the first time as a big flare came through on April 23. Conditions reached what is called “KP-8”, essentially guaranteeing that at least some color should be visible from the auroras deep into the Southern Plains.

Elizabeth was out of town on the night of the 23rd, so Sam and I had free reign to shoot our shot and try to find the elusive northern lights at a latitude as far south as Oklahoma. There were some false starts and missteps, and some fundamental misunderstanding of the goal of the evening, which was to find the patch of ground with the darkest sky between it and the northern horizon. We settled on a location that was foolishly just a few miles south of the town of Okeene. The light pollution was… well, it wasn’t great.

We did get on the board (theoretically), although there was no seeing the auroras with the naked eye. Meanwhile, we had to watch on social media as other people came into that evening with excellent gameplans in Oklahoma and executed them far better.

Elizabeth and I continued to dream of our first aurora encounter. It wouldn’t be Glacier National Park in 2022 – we both fell asleep before the one night that might have worked. It wouldn’t be Iceland in July and early August, when daylight on the island can run for close to 18 hours and the remaining “nighttime” is really just a distilled twilight. Nor did we manage to make things work on a cloudy aurora-chasing attempt in Michigan in 2023. So you can understand that the concept of predicting and reacting to solar flares by being ready to aurora chase had soured very quickly on Elizabeth.

Which brings us of course to this past week. Several big old coronal mass ejections (CMEs) occurred off of the sun in an Earth-pointing direction, and the aurora-observing world sat up and took notice.

It takes a special confluence of factors to make the aurora a viable use of time in Oklahoma. You’ll need perfect space weather conditions, perfect real weather conditions, and a perfectly free schedule. The first seemed to be rounding into form, the second looked decent, and the third… was sadness, because it was the 2nd night of my string of midnight shifts. You can’t have it all.

By the time I awoke from my post-first-mid-shift slumber early on the afternoon of the 10th, aurora chasers everywhere were whipping themselves into a frenzy. The Space Weather Prediction Center was basically explicitly forecasting space weather conditions to get as aurora-friendly as they had been since the great Halloween solar storm of 2003.

I tried to stay my hand with a healthy dose of skepticism after the last few busts, but the prevailing sense was this: if April 2023 had been a solid KP-8 event, this had the potential to easily reach KP-9 and blow that one out of the water. Elizabeth didn’t care as much as I did, but I was hooked. All through the afternoon, pictures filtered in from Europe that were too incredible to be believed.

Late in the afternoon, the SWPC announced that G5 geomagnetic storm conditions had been reached for the first time in 20 years. It was a historic geomagnetic storm if only we could hold on for a few more hours before things started to get dark in North America. All over the Internet, aurora chasers reported that they were getting in their cars and finding that dark sky. I hemmed and hawed for a while before finally taking my shot with Elizabeth.

She was indeed unimpressed. “Whenever it’s supposed to be big, it always ends up busting,” she said. Which is honestly a fair reaction after our last year. But still, I tried to prevail upon her that what was happening in Europe (visible auroras in towns like Prague and Vienna) was not at all normal. That didn’t mean anything to her; she needed proof of something closer to home.

For a few ominous minutes towards sunset, there was nothing to report. Nothing in Maine or New Brunswick or anywhere (probably because it’s May and the sun sets later up there). In fact, the first aurora report I saw from North America came from… the Bahamas, of all places.

That was enough to get Elizabeth out of her chair. My shift at the office didn’t start until 11:00, and with sunset on May 10 sitting at a cool 8:23 pm there was plenty of time to go somewhere local to see the auroras and then get me into work. The best local option (and best is a relative word here on the south side of the OKC metro) was to go to Lake Thunderbird. So I threw the camera (with two fully charged spare batteries), tripod, and two lawn chairs into my car, and Elizabeth got into hers so she could follow me to Thunderbird’s South Dam Campground.

We arrived at the South Dam area before twilight had even leaked out of the sky. There was plenty of activity into and out of the area. Naively, I thought that maybe the aurora-watchers had gotten wind of what was happening and were flocking to the darkest skies Norman had to offer. As I would learn over the next two hours, the answer was much simpler: people were driving to the boat launch to go for drunken Friday night joyrides. A sheriff posted up at the State Park made hay in passing out some sort of tickets over the course of the night.

We parked our cars up at the campground bathrooms. I had a brief moment to reflect on the view from this location, which was actually quite beautiful – the bathroom was on a bluff surrounded by campsites, with a sweeping view of the lake below. Right at twilight, with campfires burning, it made for a nice, homey view. But for the purposes of viewing an aurora, we needed to get away from artificial light and look northward toward the heavens. We followed one of the walking paths northward toward the boat launch, coming through a shelter of trees. When the view opened back up again, I was briefly stunned into speechlessness.

“Elizabeth… is that it?”

In the sky to our north, up to an angle of 50 degrees off of the horizon, the pale blue of late in the dusk hour was lit up by an equally pale pink. If this was the aurora, then there was no way around it: what we were seeing was an all-time solar storm. Getting the aurora off of the horizon in Oklahoma is damn near unprecedented in my lifetime, Halloween 2003 notwithstanding. Doing so before the sky has even gone dark? Unthinkable! So I didn’t blame Elizabeth for showing some skepticism and setting her fancy new iPhone up to take a 10-second exposure of the northern sky. When it was done, she looked and squealed. “Look!”

No way.

We spent a few minutes exclaiming at our first ever viewing of the northern lights together, then settled down to try and document and enjoy them. Elizabeth had the very simple method of pointing her phone in the sky and exclaiming at the pretty pictures. For me it was a little tougher; I’ve always been camera-illiterate despite the desire to be a Real Photographer, and this was the one chance I was ever going to get to do something like this in Oklahoma. And I was fumbling it by not getting the camera to actually take pictures because it was stuck in autofocus instead of manual focus. After some cursing and quick looking up online, I took a few deep breaths and got it figured out. And then we were off. Well, almost off. It turned out that the original spot Elizabeth and I had set our chairs up in was on the campground side of the dam road instead of the lake side, which meant that big trucks kept roaring by us with their KC lights all the way up every minute or two. That meant that we needed to drag our chairs, my camera and tripod, and our own selves into the tall grass next to a campsite across the road to be closer to the water.

By now night was falling more completely and I was awed to see that the aurora had come all the way overhead. And when I say all of the way overhead, I do really mean it. You could set up your camera and point it back toward the southeast and catch brilliant pink glow over the campground.

Elizabeth has already told me I’m not allowed to buy this as a canvas print until I buy our wedding print, which is honestly fair. But there will come a time in our new house where that photo (potentially degrained a little bit) is printed in canvas on our guest wall.

A day or two later, a photo made the rounds that showed the different colors of the aurora and what they mean.

Red is extremely rare, but down here in Oklahoma it’s often all you get to see because of how much solar energy you need to get things down here. When you think of the “bog-standard” Icelandic or Alaskan aurora, it’s always green. So the red/pink skies we were seeing was truly impressive. But for a while after sunset, there was even a window where Elizabeth’s phone camera was picking up green – and even purple! over Lake Thunderbird.

My camera (and its 30 second exposures) wasn’t seeing that, but it also was getting some brilliance.

I should probably clarify that the colors you see in these pictures are nowhere close to what the colors looked like in real life. That’s standard in aurora stuff – the longer the exposure, the brighter (and more saturated) the photo becomes. Especially for us, partially socked in by light pollution as we were, the pink glow was really pale on the horizon when we showed up. The brighter pink streaks in the picture above were visible to the naked eye, but much dimmer, and the greens weren’t visible to the naked eye at all; Elizabeth and I may very well have been the only people in this part of the state park who even knew that a historic aurora display was on.

In fact, when I called out softly to a family that was camping maybe 30 or 40 yards away from our chairs, they proved to have no clue at all. They’d been wondering if we were catfishing! Elizabeth and I pointed directly overhead to where one of the more pronounced streaks of pink were. Then we both got the chance to show off our long-exposure photography. They were all astounded – especially the father, who claimed to be an astronomy nut. Pretty soon, the little family was lining up their own long-exposure pictures of their daughter in front of the aurora, which is not how I guessed they thought their night was going to go when they were sitting around the campfire a few minutes prior. Speaking of… Elizabeth liked the picture idea.

Extra style points for the Reed Timmer point, in my opinion.

The midshift really put a clamp on the amount of time I could spend enjoying the aurora. If I needed to be back to the NWC by 11:00, I should get into my car no later than 10:30 to build in a buffer. Our first pictures were taken sometime around 9:00, so that meant we had about 90 minutes. I’d settled into a rhythm of steadily taking exposures from different angles (and then having to change the camera battery, which was a mission in and of itself in the darkness) when I noticed a person hovering by the road behind us. Deductive reasoning told me it was a grad student friend of mine, Laura. She’d DM’d me as soon as Elizabeth posted the first picture she took onto Twitter to ask where we were, and presumably had hightailed it down here along with some other grad students. We showed Laura our quarry so far and directed her attention directly overhead, where a group of pillars was standing out above us. I’ve never seen pillars that far above the horizon. I might never see them again like that in Oklahoma.

After we sat talking with Laura for a few minutes while watching directly overhead, the pillars started to fade. There were still ghostly pinkish-white splotches in the sky, but it was a lot easier to understand how the campers didn’t notice anything awry. And that was well-timed, since it was approaching 10:30 by now, so I needed to pack things up. With a last wistful glance up at the sky, I started packing up and Elizabeth and I traipsed back to our cars (no parking tickets!).

I was pretty amped up by the time I got into work for my midnight shift. The buzz of seeing the aurora was such that I naively thought I might not even need caffeine to get through night 2 of the stretch. I was (hilariously) wrong about that, but the pictures of the aurora that flooded in all night made it a little easier. Things had settled down for several hours right after I left Thunderbird, then a substorm hit with a vengeance in the middle of the night out west. Downtown Seattle, Crater Lake, Banff, Death Valley, the Golden Gate Freaking Bridge – all of those locations had visible auroras over them. It was awe-inspiring. I was even able to take a photo from the observation deck of the NWC that had some distinctive glow to it!

All in all… this was an incredible experience. I have said this many times, but we might have caught the kind of aurora display that comes out two or three times per century. I’m going to Alaska later this year, and I’m sure I’ll see way better up there, but to get visible pinks and pillars directly overhead at this latitude is like getting 3 inches of snow in the Sahara Desert. It’s doubly special because of where it was. I do wish I’d dicked around with the camera less and just enjoyed the show more, but getting that wall-hanger of a photo makes up a lot of that regret for me. I took the eclipse to just view and enjoy, so it’s fine to go harder documenting this one.

One more “First” down.