Before I get much further into this blog series about Glacier, I think it’s important to mention the geography of the national park and how it shaped the week Elizabeth and I spent there. When you’re planning for a trip, all you have to go off of is YouTube videos and maps. Those two things can help you do quite a bit to plan a trip, but there’s also an information gap that doesn’t get filled in until you’ve traipsed the ground yourself.

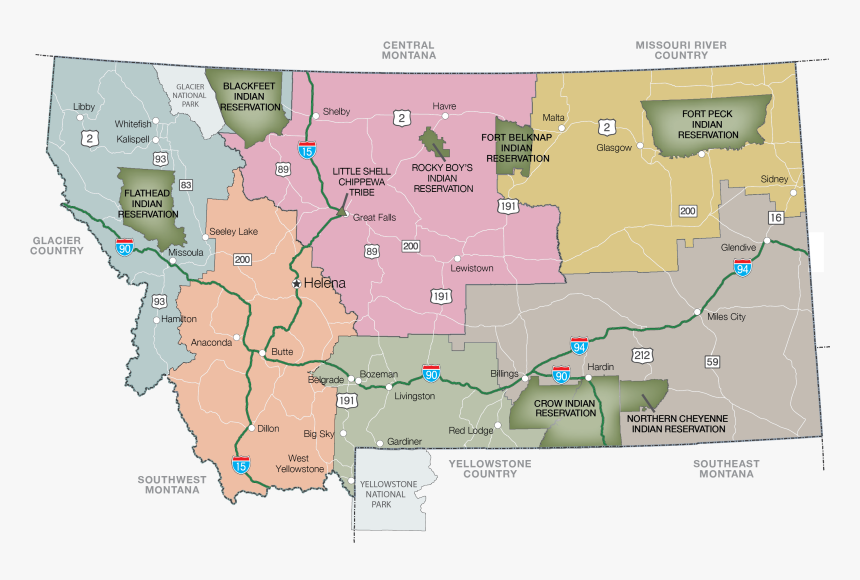

Glacier National Park is located in the far northwestern corner of Montana. On the eastern side, it is bounded by the Blackfeet Reservation that Elizabeth and I had driven (and admired the beauty of) along the periphery of the High Plains. To the north, the Rocky Mountain Front rolls onward toward the famous national parks of Canada like Banff and Jasper. Just on the other side of Glacier across the international boundary is Waterton Lakes National Park in southern Alberta. Together, they form the Glacier-Waterton International Peace Park, a very fancy name that basically shows the two parks share an ecosystem. West of Glacier, the northwestern corner of the state is ski country, with little towns like Whitefish, Columbia Falls, and Kalispell all centered in the Flathead Valley and surrounded by mountains. And to the south, the Rockies roll on in one unbroken front, unpenetrated by anything resembling a pass across the Rockies. Except for in one spot, just south of the national park, where the mythical Marias Pass was discovered just in time for the Great Northern Railway to push through it in the early 1900s. The Railway brought people through the region by the thousands, and after some quick thinking they turned the beautiful mountain country literally just north of their rail line into one of the nation’s premier early national parks. It’s that not-easy-to-access geography and the rail artery that shaped how Glacier looks today.

On the map above, Marias Pass and the rail line skirt along the southern fringe of the park between the aptly named towns of East Glacier and West Glacier, Montana. Nowadays, a highway runs through the pass along with the tracks – the famous US-2. South of that highway, no road traverses the Rockies until you get to Missoula/Choteau. North of it, you have to go well into Canada.

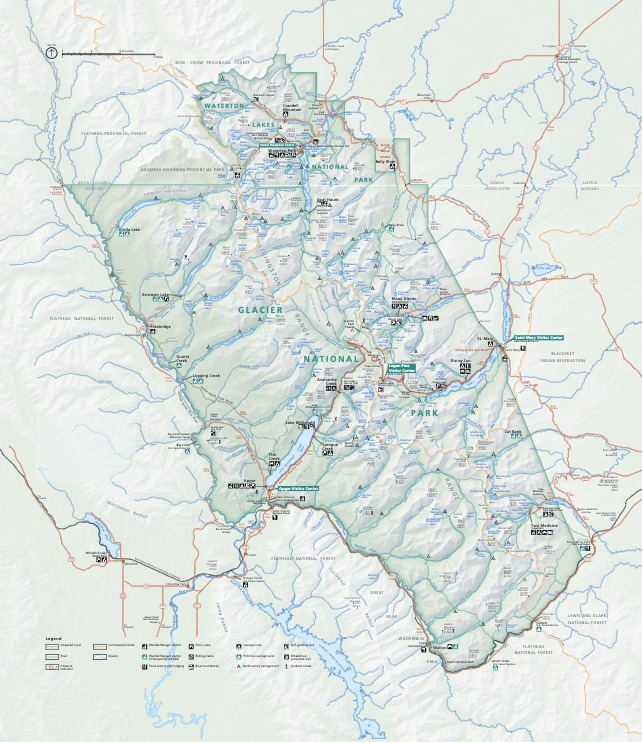

That’s what makes the road through the heart of Glacier National Park so impressive. It’s called Going-to-the-Sun Road because there’s a nearby mountain named Going-to-the-Sun Mountain, but there’s a reason millions of people just assume that the road is so-called for what you feel like you’re doing driving into it. Going-to-the-Sun Road manages to cross the continental divide at Logan Pass at 6,647 feet by climbing along the sheer face of the Garden Wall on the west side of the park while approaching from the shores of St. Mary Lake on the east side. As befits a road through some of the most hostile conditions in the lower 48, Going-to-the-Sun Road is closed for a majority of the year. It opens with the coming of spring in the alpine passes every June, and closes when winter shuts the passes down in October or November. We planned our trip for mid-July not least because it would mitigate the chances of a late open of the road. Unless something totally unprecedented happened.

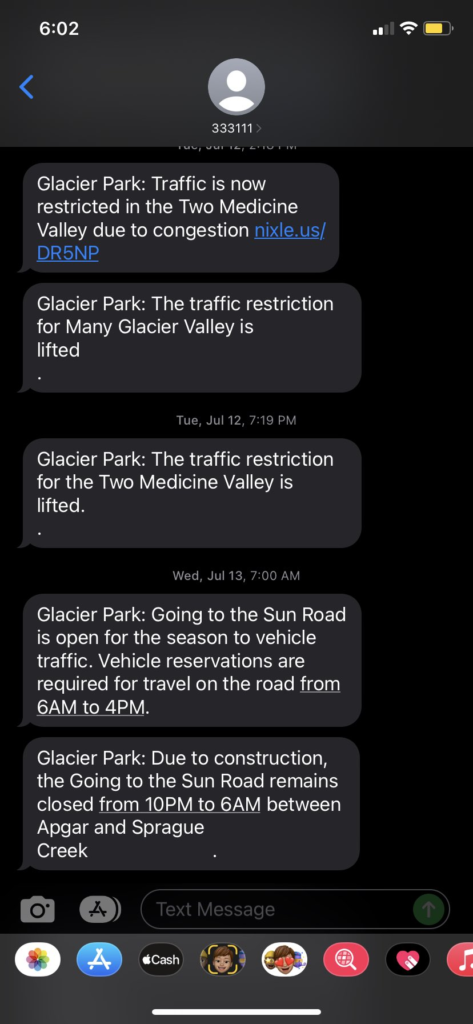

The early 2020s were constantly an exercise in getting used to unprecedented things. The last we had heard from any official source before departing on July 12 was that the road would not open any earlier than July 13. No one was making any promises that the road would be fully plowed, guardrails installed, and passenger traffic cleared for travel by that date either. The road was open to Avalanche Creek on the west side and Rising Sun on the east. To get from one side of the park to the other, you’d have to take the hours-long detour on US-2.

Elizabeth and I had split the park by section to attack it over the following week, much as we had done with Yellowstone in 2021. You can reference each section on the map above. We spent the night of July 12 in our cabin north of Babb, the little town at the highway intersection near Many Glacier in the northeast corner of the park. Elizabeth and I had spent a magical couple of hours exploring Many Glacier the night before, from the famous Grinnell Point vista to the moose that nearly ran us over at Fishercap Lake. Many Glacier is also noteworthy for its access point to several of the park’s (no longer many) glaciers, such as Grinnell and Swiftcurrent Glaciers. We planned on returning for a full day on July 17 to hike up to Grinnell Glacier.

Further to the south lies the east entrance to the park at St. Mary. From here, one can look east toward the ridge we’d seen the moon rise over the night before, and the High Plains rolling for hundreds of miles beyond it. There’s a visitor’s center at St. Mary, a small village just outside the park boundary with a convenience store, and a rather large campground that Elizabeth and I would be staying at from July 15 to 19. It’s also conveniently located right at the eastern terminus of Going-to-the-Sun Road – a great launching point if only the road were open. From there, we could drive through the spine of Glacier to the other side.

Halfway across Going-to-the-Sun Road is the Logan Pass area. High up in the alpine region, Logan Pass is surrounded by stunning mountains, valleys, snowfields, and waterfalls. There’s a visitor’s center right at the continental divide with some of the fiercest parking battles in the NPS. From Logan Pass, multiple famous hikes begin, including Elizabeth and my most anticipated: the Highline Trail. If the road wouldn’t open, we’d be SOL when it came to the Highline Trail for our planned hike on July 15. We’d have to find somewhere else at a lower elevation to get up into the alpine region.

On the other side of Logan Pass, Going-to-the-Sun Road descends along the famed Garden Wall until it reaches the valley floor on the other side. The road then continues to its other terminus at Lake McDonald. The Lake McDonald area is the busiest in the park. On the northern fringe of it sits Avalanche Creek, where Elizabeth and I had planned to begin a popular hike up to Avalanche Lake the morning of July 13. Then along its long southeastern flank the road continues until you reach Apgar Village at the far corner of the lake. Apgar Village is a busy, busy spot full of lodges, motels, and restaurants. This is exacerbated by the presence of West Glacier just outside of the park boundary, where the old Great Northern Railway built their station. West Glacier is your typical tourist town outside of the national park, but maintains an authentic charm. Unlike St. Mary, which is right on the edge of the mountains, West Glacier and Apgar are squarely nestled into mountainous terrain, with big elevation everywhere you look.

Off to the north of West Glacier, in an area long known for its relative lack of crowds, the North Fork area is only accessible by a one-hour trip over unpaved roads north out of Apgar. It’s a land of long, narrow alpine lakes and sweeping mountain vistas in the Livingston Range. When Going-to-the-Sun Road was closed in 2020, crowds overran this previous backwater of Glacier, and the park was forced to introduce a timed entry system that was still in place in the summer of 2022. I had managed to get a timed entry pass to Going-to-the-Sun Road with no trouble the day they came out, but the North Fork entry tickets disappeared immediately. A few more get released the day prior, so our hope was to land some on the morning of July 13 and visit the North Fork area on July 14 while we were over there.

In the southeast corner of the park lies the Two Medicine Valley. Once the premiere location in the park in the railroad days, Going-to-the-Sun Road has sapped its relevance. Now it’s mainly a pretty place to go check out the multi-colored rocks out at Two Medicine Lake, and a near-neighbor to one of Glacier’s most fascinating geological features – the Triple Divide, where the continental divides between the Atlantic and Arctic, Pacific and Atlantic, and Pacific and Arctic basins all meet. I really wanted to hike to Triple Divide Peak and see this.

And finally, a mention of the local geography would be incomplete if I didn’t mention Waterton Lakes National Park, which is located in southern Alberta. We would drive there from St. Mary on July 16. Waterton Lakes contains the three lakes named “Waterton” and a famous hotel known as the Princes of Wales. It shares a border with Glacier and hikers are actually able to hike from the U.S. into Canada. Boat tours on Upper Waterton Lake can also cross the international boundary. We hoped to hike the famous trail to Crypt Lake while in Waterton, although a day after Highline we might be too tired to do so.

Ok. That sums up the geography. You can see how Going-to-the-Sun Road’s closure really affected Elizabeth and myself. Instead of a scenic drive across the spine of Glacier the next morning to Avalanche Creek, it would be a roundabout 3-hour detour on U.S. 2 through Marias Pass and up through the McDonald area. I had a 6:00 a.m. alarm to roust us out of bed in time to find parking at the competitive Avalanche Creek lot. You can picture Elizabeth and me, peacefully conked out in the predawn glow in our little cabin, feeling the cool mountain air pouring in through the mountain window.

6:00 a.m. struck. My alarm went off. I fumbled for my phone in the dark in a half-awake stupor, and noticed to my surprise that I had just received a text one minute ago. It was from the Glacier National Park road condition opt-in messages, that lets you know when a certain part of the park no longer has parking or whatever.

My eyes opened wide. I was completely awake.