The idea of relativity of time gets funnier the closer I get to this project. August 19th, 2021 feels like eons different than August 13th with the benefit of hindsight. That’s probably because I was blogging about August 13, and the first views of the Tetons, and how I felt pre-proposal, and all of that back in October of last year. Now it’s June 2022 as I’m getting to our last full day in Yellowstone, and they feel so far apart. But really, when I woke up on another gloomy morning at the Canyon Campground, I was still getting used to the idea of having a fiancee, which I’d only had for under 6 days! Relativity of time can be a funny thing.

Since Delta Lake, though, all of our time had been consumed with sightseeing. So many historic sites in Grand Teton, and famous photo ops, and of course the billions of boardwalks past thermal features in Yellowstone. This morning was supposed to be a capper hike to end the trip. Elizabeth and I planned on making the hike alone, in the east corner of Yellowstone. My older sister’s good friend Aubree worked at Yellowstone for a summer and provided us a guide of all the best trails in the park, and her personal favorite was a hike up Avalanche Peak. It’s a pretty short trail by the standard of “big, trip-defining hikes” – 4.5 miles from the trailhead to the peak and back down to the beginning again. That belies the 2,000 feet of vertical climbing one must do within those 2+ miles, a straight-up gauntlet that begins in the high terrain already east of Yellowstone Lake and concludes on a peak 10,500 feet above sea level in the treeless tundra of the Absarokas.

Surely a climb above the treeline would be pretty nifty to see on a sunny day, or even a smokey, hazy piece of crap like the ones we’d seen to start the trip. But after taking a morning drive down US-14 through the hairpin bends past the lake and into the Absaroka Range, it became clear that we would not have a sweeping vista of a view. In fact, the cloud level was not far off the base of the mountain, and a thick deck of stratus was rolling along overhead. Nothing daunted, Elizabeth and I decided to push on with Pam to the trailhead and see what we could do with the conditions we had. Weather had managed to ruin views, but it actually hadn’t managed to ruin any of our plans so far this trip, and there was no reason to change that now.

My fear that we might get there too late in the day to get parking at the modest Avalanche Peak trailhead turned out to be extremely unfounded. In fact, Elizabeth’s Subaru made exactly one vehicle in the pull-off area for the trail. That seemed… not great. Was everyone just opting out of hiking because of the weather? Or was something else in play? It was quite chilly – I unironically had pulled the puffy vest out of my suitcase and had layered it on to add some warmth as morning temperatures were struggling to even get out of the 30s. But still. No other cars? Weird. Pam decided not to join Elizabeth and me on the hike. It turned out my fear of running her right into the ground the day before (“you can nap when you’re dead”) was well-founded, and she volunteered to stay with the car in the little roadside pull-off and take a nap. I felt uneasy leaving her there alone, but where else should we leave her? National park planning isn’t always the most convenient.

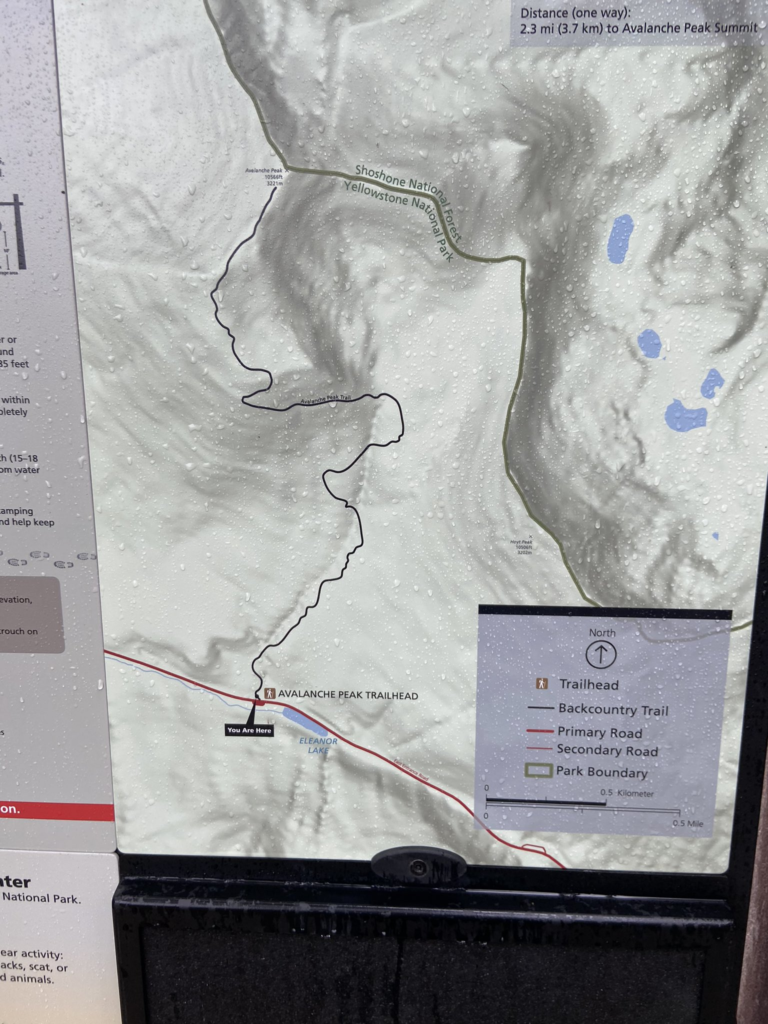

Across the highway, the trail literally takes off straight up the mountain. We read the sign with the map above – and perhaps more critically, we read the part about how this trail is frequently closed in August and September because of bear activity. Apparently the bears like the berries along the side of Avalanche Peak. Ok, that’s a little spooky, particularly with not a soul around. Elizabeth had bear spray strapped into her hip, but the best bear attack preventative is to not see one at all. Both of us were on edge as we began climbing the mountain.

It was a rugged, unrelenting climb. The average grade for a 2,000 foot climb over 2.2ish miles is 17%. And that’s about what the entire trail was – a steady, unrelenting uphill largely devoid of the usual switchbacks. Within a few minutes, I was sweating and shucking off my outer jacket despite the fact that the day was closer to the freezing line than anything I’d experienced in 5 months. As much as the altitude and the grade surprised and dismayed me, they affected Elizabeth worse. Soon, she was gasping for the thin, damp mountain air and necessitating stops every few minutes.

One advantage this did give us – we received definitive proof that the trail was not closed, in the form of a whistling hiker who overtook us from downhill. He was a clearly In-Shape dude with an accent that I’d wager was either East or South African, off for a nice little solo jaunt up to the peak. We chatted with him briefly before the dude disappeared uphill into the thickening mist that surrounded the trees and the trail. I felt a little better after that – after all, if there was a bear somewhere uphill, it was going to hear his whistling and either get out of the way or decide to maul the person making the off-key noises, giving Elizabeth and myself relative peace of mind.

The going remained super slow all through the opening “straightaway” – a process that encompassed a little over half a mile and 600 feet of elevation. Elizabeth couldn’t go more than a minute or two before needing another break, and her gasping was somewhat concerning to me, but I’ve seen her gut out trails like this before. The issue was that we’d entered the cloud deck. This part of the trail was already pretty low-visibility, given that the slopes of the mountain are heavily forested, so the only thing we could see in every direction was the shape of big hulking lodgepoles disappearing into the mist. The only exception to that low visibility was a brief, steep meadow a little after the half mile mark that only served to show that we were up in the clouds after all.

Slowly and steadily, Elizabeth and I cut our way up the trail a couple hundred feet at a time. I marked off the progress – nearly halfway up, 1.1 miles, 1.2… however fall AllTrails told us. We finally took a big left and realized with a jolt that we were at the treeline. That was when I realized – the trees were actually blocking a steady breeze up here at the level of the jetstream. It got chilly quick along the exposed rocky ground, and the visibility somehow dropped more. It was truly eerie. Elizabeth and I looked at each other, and confirmed that neither of us could shake the image of a bear or a mountain goat emerging from the gloom and wrecking our shit. That, plus the futility of continuing with near-zero visibility, decided us to head back down. It’s not giving up on a hike if you have a couple of thin excuses to support you, right? Besides, I was hungry.

The hike down was much easier and gave me more time to enjoy the beauty of the mountain forest, completely away from humans. It was so shockingly quiet. I could hear Elizabeth’s ragged breathing, and an occasional breath of wind among the pines, and nothing else. That’s what being in a national park is supposed to be like.

After a while, I realized I could hear two voices downhill from us, heading our direction. To my great shock, it was Terri and Garrett. They’d arrived a little after us, and were trucking up toward the treeline on their own. Terri was using portable oxygen to help her out, but otherwise I was struck by how much better the two of them were handling themselves in the altitude than they had been at Delta Lake a few days ago. In fact, they looked to be in as good of shape as Elizabeth herself, much to my shock. We wished them good luck and continued back down.

Much to my relief, there were no bears blocking the path back down. Even more to my relief, Pam was still in the Subaru when Elizabeth and I got back down. Avalanche Peak might have been one of the most underrated parts of the trip – if the weather hadn’t interfered. Instead, in a trip full of high expectations that didn’t bust, I’d say this was our most high-profile bust of a planned activity. Even then, I did enjoy hiking a remote mountain with Elizabeth where I couldn’t hear anything else. It added an element of solitude not easily found in a national park trip with family.