We all needed a down day. May 20, 2019 had shaved months off of the lives of field researchers, forecasters, and myself. The Mangum tornado, its low visibility, the inadequate and overstressed road network, and the unexpected collapse of the rest of the severe weather outbreak left a bitter taste in everyone’s mouth that night and virtually guaranteed a down day would be in order on May 21. Besides, much of the area at enhanced risk for tornadoes on May 21 would be well out of the operational domain of TORUS:

In hindsight, not chasing that part of Kansas was a mistake.

But even on the morning of May 22, there was no particular reason to feel regret at the down day decision. I felt refreshed after having chased all the way up into Nebraska and back into Oklahoma over 3 of the previous 4 days. And besides, there was reason to believe that today was the day worth staying in position for in Oklahoma.

In fact, it looked like we might not have to go far at all to get the storm we wanted. Morning models showed CI occurring from near OKC along the I-44 corridor all the way up to Tulsa or so. Given the eastern limits of the allowed operating range, Tulsa was out of the question. But if a storm wanted to initiate around Piedmont and race off to the northeast from there, we could make a play on it more than worthwhile. The biggest issue was that forcing would remain nebulous, with the giant upper closed low pivoting around and around and rising heights showing up on CAMs right around showtime in late afternoon.

For my part, I woke up skeptical about the severe potential:

And realized very quickly that I was stupid:

The warm front was going to reach the target area, so we were going to have a play

Elizabeth and I headed up to the Weather Center by mid-morning to join our vehicle teams. TORUS was reconvening at the Holiday Inn Express in Norman, where the other schools were bunked for the night, to get ready for the weather briefing. After the torture of meeting for over an hour on May 20, every briefing from here on out would pointedly be less than that amount of time. Excitement once again began to build as we got the results of the first sounding of the day:

After trying to figure out how we could play the storms if the dryline was going to sharpen directly over I-35 with the warm front somewhere near I-44, the PIs decided that there was still time to nail down exactly where we needed to be to avenge the disgruntlement of two days ago. For now, we could drift slightly north into Oklahoma County and await developments. So, lunch at Pops.

The lidar truck was the very last vehicle to make it to Pops as a result of a navigational error that Mike made in telling me to get off of I-35 a mile early. We nearly drove into Arcadia Lake before backtracking and sheepishly arriving at the mega-tourist-trap. The good thing about Pops is that it’s at least reasonably capable of handling a surge of several dozen patrons, not something that every restaurant in every town on the Plains can manage. The other good thing is that there was plenty of grassy space outside it for a slightly antisocial Nolan to wander around. The bad news is that the brown ocean effect made for a deeply uncomfortable stroll. The environment, fueled by that brown ocean, continued to look better and better right over our heads.

And the funniest thing of all? The dryline continued to not mix eastward. All of a sudden, CI didn’t look like it was going to be in OKC, but somewhere further southwest.

We weren’t going to look this gift horse in the mouth. Just as the afternoon sun passed its zenith in the hazy skies, the PIs made the decision to pack it back up and head southwest. The sky rewarded patience: soon, an updraft was visible in the Red River bottomlands. Storms were going up behind us, but they were in the literal and figurative rearview.

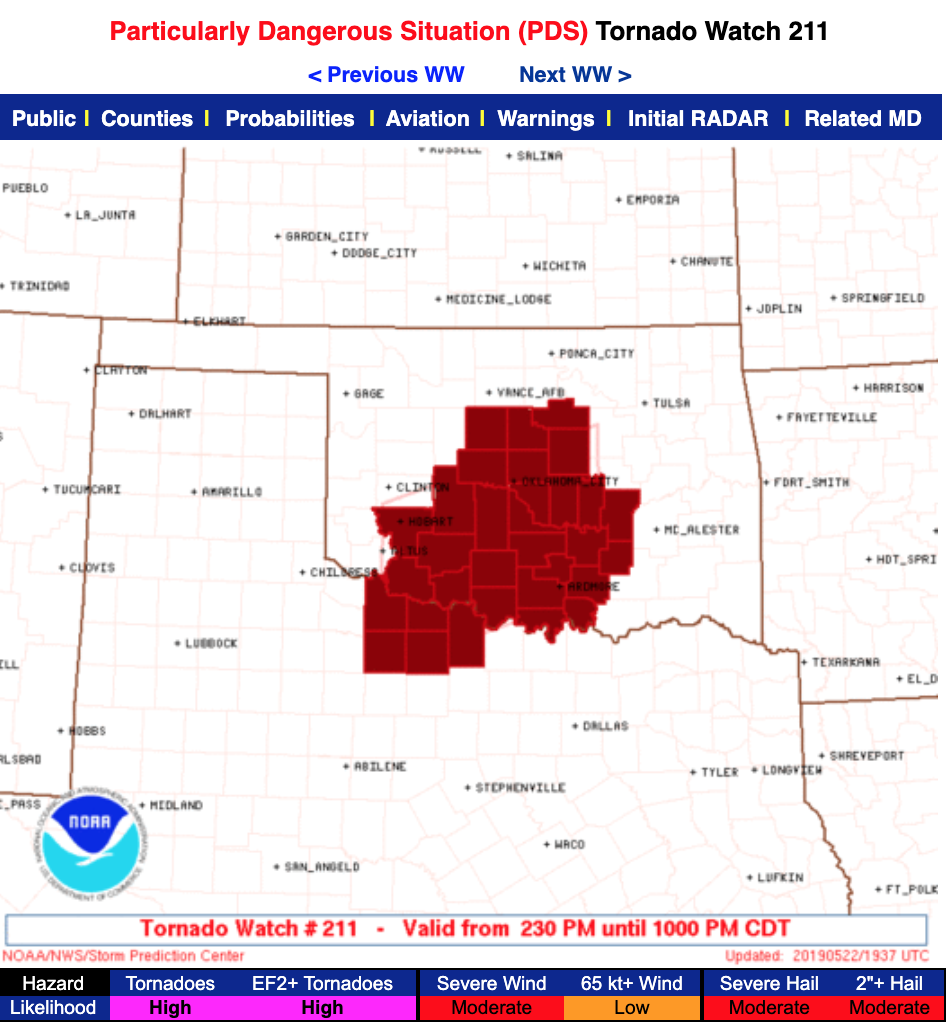

Along the way, we got a sobering reminder from the SPC about the trajectory the day was taking. From a low-end enhanced risk, a moderate risk corridor had been introduced along I-44 up into Missouri, and at 2:30 the SPC upped the ante.

That’s a particularly dangerous situation watch all the way into North Texas, where no severe weather risk had existed in prior severe weather outlooks. The southwest trend was clear, and it was putting the OKC metro under the gun. Meanwhile, down by Lawton:

It didn’t take a real genius to tell that this storm was on the same path as famous “44 runners” that initiated in that area, including May 3, 1999. That may have accounted for the sober mood in the lidar truck as I bombed through Norman on I-35. I know all three of us were thinking the same thing without saying it – was this peaceful college town in the direct path of a storm that may be producing violent tornadoes within the hour? What about our homes? Our possessions? Our friends?

At least two of my friends were not in Norman waiting for the storm, because Sam and James were underneath it outside of Lawton. By 4:20, they were reporting classic signs of a storm about to produce a tornado:

Meanwhile, Mike was once more plotting a wide berth on the supercell for when it turned right. I pulled into an industrial lot a few miles south of Lindsay, Oklahoma on OK-76, and we got the lidar up and running. I bustled into the back of the truck, where I was quickly learning how to get soundings up in the air very quickly. Unfortunately, I discovered that a disaster had taken place: somehow, our good regulator for the helium tanks was missing. In the intervening years, I don’t remember how it happened, but the upshot was that I was stuck using a slow regulator that only let helium out milliliter by painstaking milliliter. I spent minutes inside the balloon bag, trying to coax the balloon to inflate, which is why I was so shocked when Mike announced to me that we were leaving. What?

As it turns out, everything had inexplicably gone to shit. And I mean inexplicably. It was reminiscent of the severe bust two days ago, only this one was arguably worse. Our storm, an established supercell with a decent wall cloud, essentially evaporated into thin air. I could not tell you why. Height rises aloft? Maybe, but you would think a few centimeters per second of subsidence wouldn’t be enough to take down a healthy supercell. Entrainment of dry air or capping? Didn’t see any on soundings.

Maybe the aerosol conspiracy theorists were onto something. The skies in central Oklahoma, while not under the same stratus miasma as they had been on May 20, were hazy with the persistent smoke of Mexican wildfires. Could it be that the smoke interfered with the storm’s ability to maintain itself, similar to how the Mangum storm had abruptly disappeared? I didn’t know then, and I don’t really know now. I’ve seen presentations and papers on the subject, but I am a natural skeptic of trying to ascribe failure modes of any one or two particular storms to something. Maybe it was the smoke. Or maybe it was just a poorly timed RFD surge that wiped out the near-surface inflow. Whatever it was, I’d gone into the balloon bag preparing for May 3rd all over again, and came out confronting a blue-sky bust.

TORUS stayed persistent. Mike continued to guide the team northeastward, following a series of updrafts that were at least trying to become supercells, from Lindsay to the small town of Lexington in Cleveland County. It was there, well before 00:00 UTC in late May, that we had to admit it: we’d gone chasing waterfalls. The day was a complete and total bust, with not even much data collected to explain why it had happened. There was nothing left to do but call it quits. Meanwhile, east of Oklahoma City:

A localized tornado outbreak occurred in the soggy region east of Oklahoma City, up toward Tulsa and on into southwest Missouri. While TORUS couldn’t be there to see it, there was an element of “insult to injury” added to it. No wonder I felt beat as we got back onto Highway 77 and headed toward Norman. A car flew by us along the way, with the idiots slowing down to get a good look at us before zipping by, which failed to improve my mood. It was only later that I discovered those idiots were James, Sam, and Moriah, on the way back from one of their worst busts ever as well.

Even weirder: we were apparently predeploying westward tonight. It made sense, as there was still sun in the sky and we could get a jump on the next day’s anticipated severe event in the Texas panhandle. But I’d been very confident that we would be back in our beds at sunset, and subsequently had not packed much in the way of spare clothing for the trip. It wasn’t a huge issue for the time being, but what I didn’t know was that May 22 represented the first of an intensive 7-day stretch of consecutive TORUS deployments away from home. I would be a stinky guy by the end of the trip.

Our spirits recovered in the lidar truck as I drove west on I-40 toward Elk City. Getting usable data on the Mangum tornado probably helped avoid the worst of the double crushing blows we’d been dealt in the last three days, but still, there was a sense of disbelief at what was going on. The surrealism peaked when a supercell formed near sunset over Wichita Falls of all places, split, and briefly threatened to do something spectacular before nocturnal cooling claimed it as the latest victim of central and western Oklahoma. A few more supercells would occasionally spawn themselves in western Oklahoma on the low-level jet over the evening, but none ended up doing anything sustained.

TORUS staggered into Elk City pretty late, and got ourselves settled and ready for another recharging night of sleep. Elizabeth somehow had failed to get dinner on the drive here (I ate at some point, although the details are lost to history). So I joined her on a walk along scenic 7th Street near the Hampton Inn, trying to find an open restaurant. That area has seen some growth in fast food chains since 2019, but at the time, nothing was open. So Elizabeth was stuck with a dreadful meal from the Hampton Inn’s internal stock of meals (mac and cheese maybe? Elizabeth probably remembers this scarring experience more than I do). I headed back up to my hotel room, where Glen and I stayed up a little while watching the progress of a rogue barge that had come loose on the Arkansas River and was threatening to wipe out the I-40 bridge. After it became clear that the barge would not, in fact, do that, we turned out the lights on May 22. Our luck was about to change.