Now that TORUS 2019 is 5 (wow) years in the rearview mirror, the memories are getting a little fuzzier. Some of the big days still live on in my memory and always will. May 25, 2019 will always have a historical footnote in the great 2019 tornado outbreak sequence – but that footnote occurred hundreds of miles to the east of the sprawling TORUS project (and any other storm chaser, for that matter). What little memory remains of that day, which is fading in my mind, revolves around the fatigue of multiple days of deploying in a row as well as the proliferation of all the damn water.

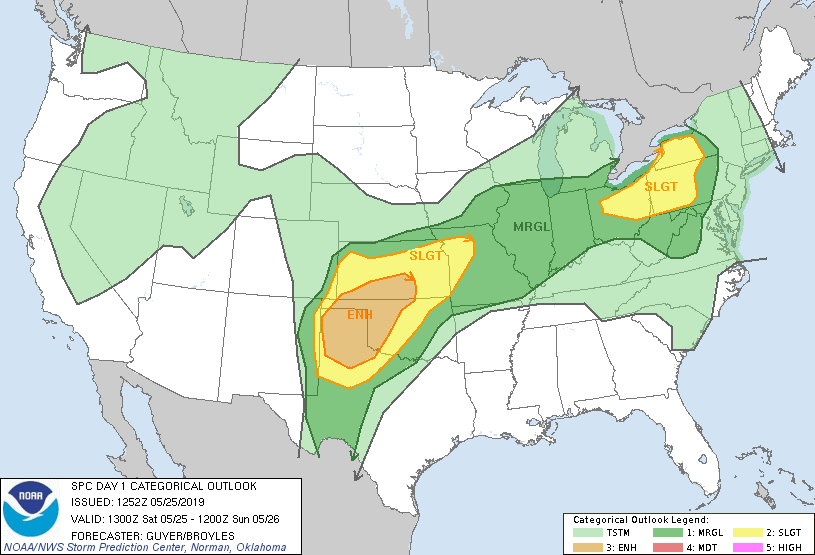

The morning of May 25 began in Amarillo. Again. The 2019 severe season on the southern Plains was finally approaching its denouement after a never-ending month of May, but there was still one more robust-looking severe weather day before we might finally move north into the central Plains on May 26.

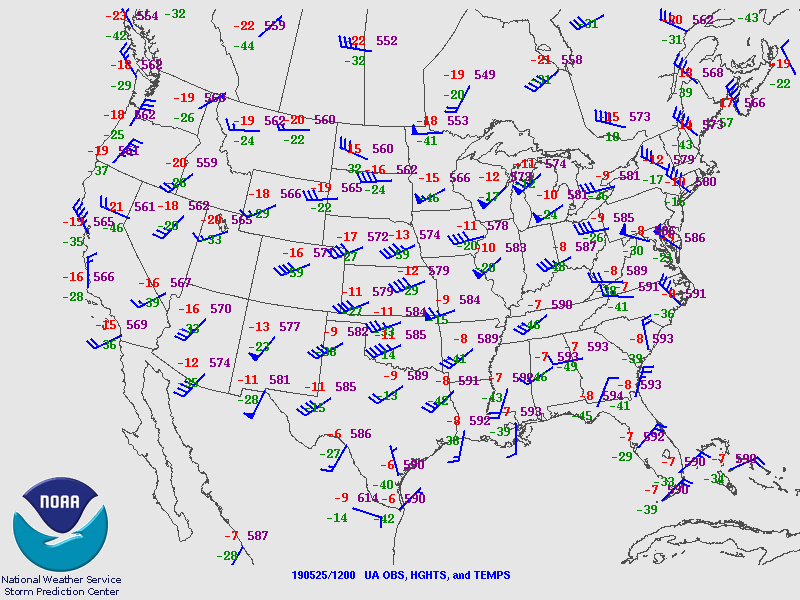

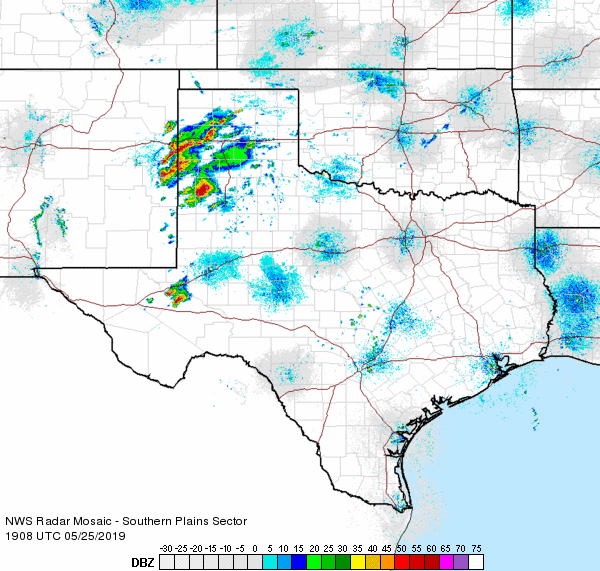

The next shortwave trough to reach the Southern Plains could be seen that morning over the desert Southwest, within that ever-present May 2019 southwest flow.

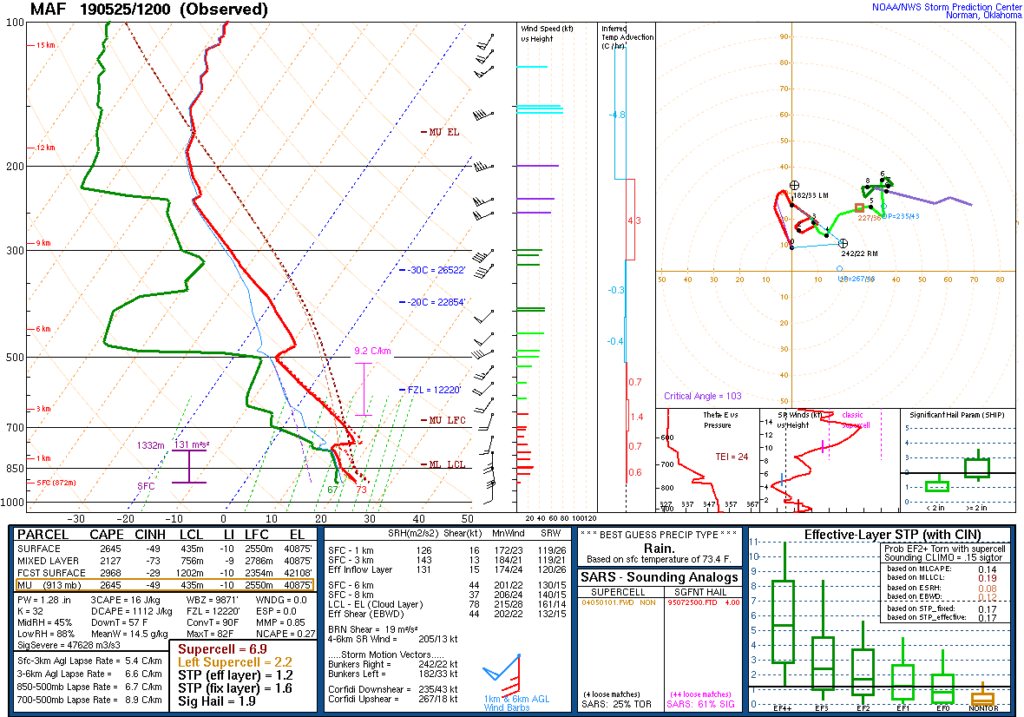

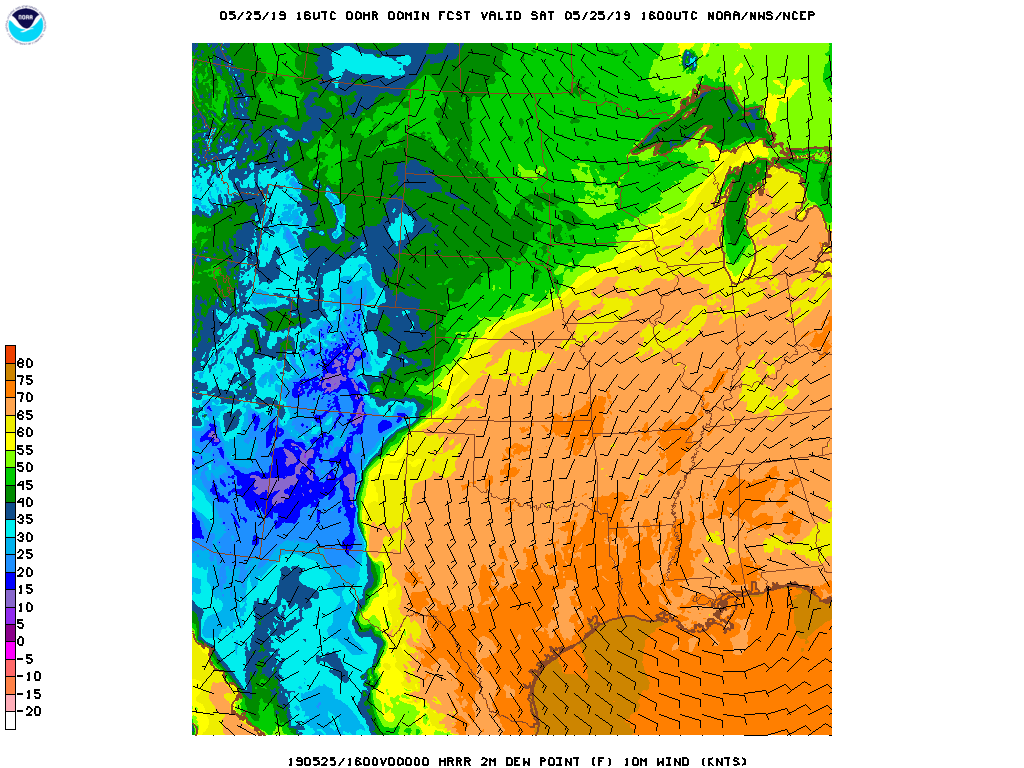

It was going to be an early CI kind of day, as 12Z soundings showed an anomalously deep moist layer for the Texas High Plains and little capping above it.

And if the storms got going early, then we needed to get going early. The convoy was on the move down I-27 south well before noon in time to see the sun come out for the first time in days – a weak, hazy sun poking in and out among already-towering cumulus clouds that were streaming northward along the dryline.

Our plan was to hang out in Lubbock, further away from the semi-stationary frontal boundary that had been an ever-present part of the forecast ever since it first lifted north across the Plains prior to the McCook tornado 8 days ago. Here, better low-level shear seemed likely from the more backed surface winds, and a discrete storm mode also seemed likely off of the dryline than nearer the boundary. Given the degree of forcing and the depth of moisture, upscale growth into a sloppy mess in the evening was almost a guarantee. But if we could get something discrete early on, there was a decent chance of something tornadic. It’s easy to ascribe your feelings later on to the day, but this past week had been topsy-turvy. Extremely impressive-looking days like May 20 and May 22 had done practically nothing in our area. Meh-looking days like May 18 and May 24 had led to solid deployments. What would a middle ground, decent-looking day do?

Well, we had the chance to find out really early. By noon, storms were already going up along the dryline before we’d even gotten to Lubbock. Mike told me to pull off the big old lidar truck into a Pilot near Tulia so we could fuel up and grab some Subway. His instincts are usually right – I had this internalized by this point. And lo and behold, here came the ahead-of-schedule MD:

Since storms were already approaching I-27, our initial target spot of Lubbock was looking more and more like a pipe dream. Mike told me to get off the interstate and prep us for a deployment on a supercell that was west of Lubbock and racing northeastward.

A little bit of repositioning (exactly how we got there has been lost to history), but eventually Mike, Liz, and myself were set up and ready to get some fabulous lidar data.

Now is when I should probably bring up the “support” vehicle. You see, in the shiny bright lights of the first year of TORUS, somebody at CIWRO or NSSL (oh my god, this is long enough ago that it was still OU CIMMS instead of CIWRO. Oh my god.) had thought that the project would be the darling of the media. The VORTEX project reborn. Twister come to life in 2019. So they enlisted a rental car whose main job would be to follow the action and if possible, carry media members who wanted to ride along with the project. And there was quite a bit of positive local media that came out, but much of it seemed to be confined to print or web traffic. The support car did not fill out its intended purpose of having Cantore or Roker or Zee going to battle with the scientists.

But the vehicle still existed. Thus far in the project we had avoided the need to have the vehicle, but herein lay the rub. Liz and Manda Chasteen both had a wedding they needed to attend that weekend. Their plan was to take the vehicle back home, fly (?) to the wedding if needed, and then get right back and use the support vehicle to catch TORUS wherever it may be the day after Memorial Day. So far, this is a straightforward plan. But that plan also meant that someone had to be in the support vehicle throughout the day of May 25. Logically, this meant pulling someone out of the Mobile Mesonets – do you really need *4* people in one of those trucks to drive circles around a tornado? The problem – nobody in a near-storm mission was happy to volunteer to take a day following around the good old lidar truck. This is an understatement – they all flat-out refused. Mike grew increasingly exasperated with the refusal of the undergrads he was asking for help, until he finally said he was going to flip a coin and walked away in disgust. The coin came up on my classmate Christiaan Patterson. She was in one of the near-storm missions (I think the windsonde vehicle) and was NOT happy to be moving to a spot where you couldn’t see the storm. So I was sort of grimly amused by the view from our first deployment spot:

Yes, this was the sort of grungy, smoky shit that Mike, Liz, and myself had been staring at for days. Yeah, science isn’t always sexy. Let me tell you something – in my time at OU, I stared at that exact scene through 3 different field campaigns – once in the lidar truck in TORUS 2019, once with PERILS at the coptersonde flight locations in 2022, and once again with TORUS in 2022 when Mike roped me into the NOX-P scout with him. Nobody can say that I didn’t pay my dues when it came to “helping collect data without getting the cool storm chasing experience”. If I complained, then I had earned that right. So maybe I was a little cynical listening to Christiaan complain from the support vehicle, which had been attached to follow around the lidar truck and give me a hand with soundings.

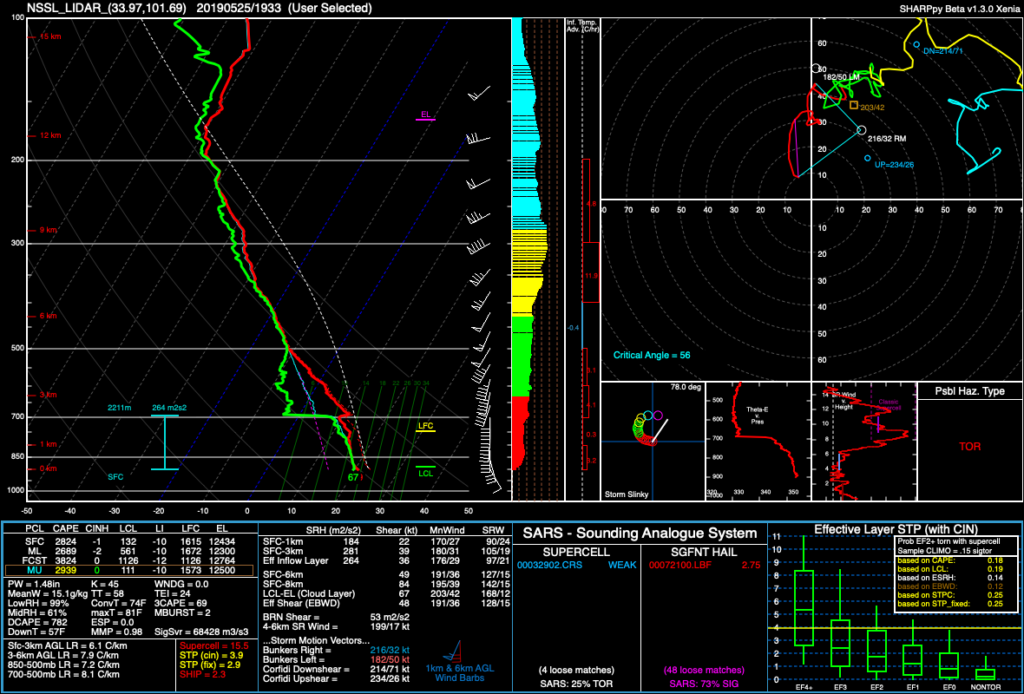

On the subject of soundings, if you were curious what kind of environment it took to reduce visibility on the Llano Esacado to nil…

That will just about do it.

There was almost nothing of interest in this deployment. The environment was moist, there was low-level shear, and yet the amount of miniature updrafts and the meridional flow aloft were clearly encouraging the supercell to try to grow upscale and it remained outflow-dominant. Not that I ever saw. Instead, I was trying to figure out where the hell I would take a leak on a farm-to-market road near Hale Center, Texas. Eventually I settled on the most logical solution: walking the quarter-mile to the end of the nearly submerged dirt road we were pulled off on, and peeing with the helpful shelter of pure distance.

This wander brought the shocking and gratifying realization that wind turbines are LOUD. Like, when you get beneath one of them, it legitimately sounds like a jet engine taking off.

And that was the most exciting thing that happened to us all deployment. The sky was gray, then it was kind of less gray, and then it was gray again. The storm continued shooting northeastward, driven by the insane May 2019 upper-level jet, and eventually we had to undeploy. Honestly, it was probably for the best, or we might have been testing the lidar’s capability underwater.

Trailed by the little support vehicle, I hauled ass in the lidar truck through Mike’s convoluted stairstep northeastward across the Caprock. Navigating the vehicle was one thing – it was a whole other for him to coordinate the entire project, especially when everyone else had their own best interests at heart instead of focusing on a coordinated dataset. It was little wonder that in the course of this May 23-25 stretch in the Texas panhandle, Mike bent my Texas Delorme’s so much that pages started to rip out (those same pages were finished off on a dusty day in the panhandle with Stephen, Elizabeth, and Scipio in April 2022). On top of that, the storms weren’t cooperating. By the time we rolled through the tiny hamlet of Quitaque to reach the bustling, population-of-300 metropolis of Turkey, it was clear that this initial supercell was both too fast and too outflow-dominant to care about. But the beautiful thing about May 2019? If your storm wasn’t doing it for you, there was always another one. Always. Just wait a bit, give the car a little gas at Allsup’s, and then get ready for the dryline to fire again.

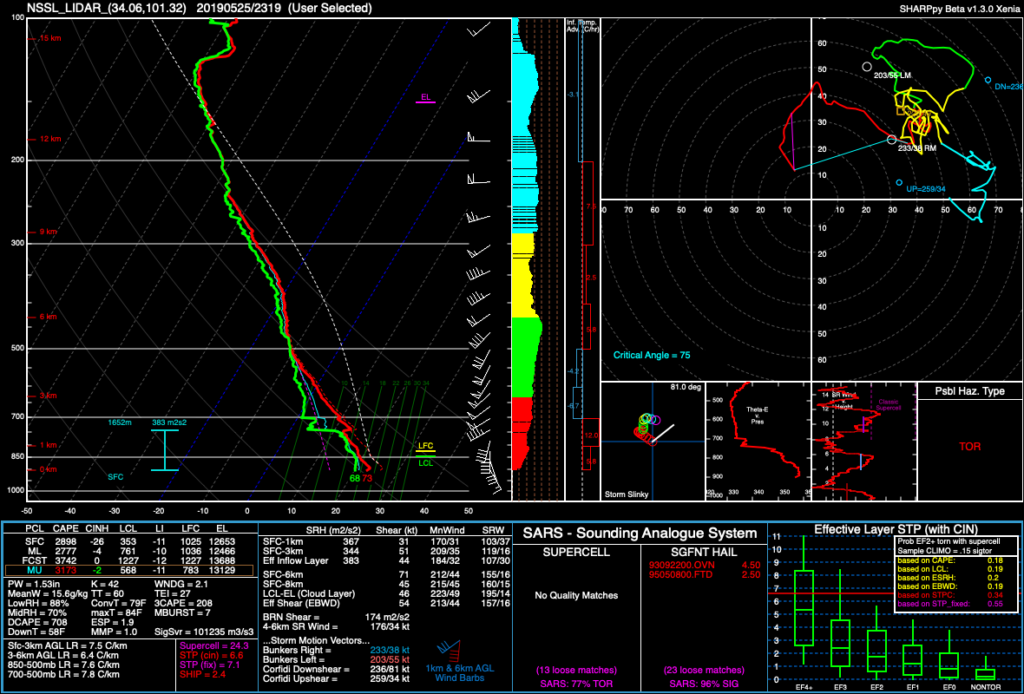

By late in the afternoon, the dryline had fired again, and another supercell was bearing down on the I-27 corridor. This was rather ideal from a deployment perspective – everyone was already downstream and could fan out as the storm approached, and the road network was much better on the Llano Estacado than down here in the Caprock. Our little two-car convoy made tracks back to the southwest to set up for a deployment not far northeast of our first one – this time at the intersection of 207 and 97 north of Floydada.

Outside of the fact that this time the intersection was a little less flooded, and the fact that no dirt road led right up to the nearest wind turbines, it could have been the exact same scene. We got the lidar up and scanning – our team was a well-oiled machine by this point. I immediately got things set up and helium flowing into a balloon while Liz got the lidar booted and scanning in a matter of moments. In deployment 1, I got the balloon in the air 15 minutes after the lidar started scanning. In deployment 2, the time lag between the two was 14 minutes. That kind of consistency spoke to a sort of professional pride I took in our job; as silly as it was to feel professional pride in a temporary two-week storm chasing job where I served as a glorified chauffeur for the two real scientists, there really was this sense that we were out there doing something cool and important and not at all predicated on glory-chasing (rip Jonas. Bill Paxton was too mean to you in Twister).

That professional pride was intensified by Christiaan’s reaction to our day. A part of me took a pleasure in someone else having to share in our slate-gray view of the Texas skies; she did not find the humor in the situation. Instead, she ended up sulking enough to the point where I grew fed up and told her she could go be miserable on her own, because I had a job to do. Writing down those words shows what a narc 2019 Nolan must have really been, so thank you to Christiaan for not hauling off and belting me for saying that. But it did get through to her somewhat, because after that she apologized to me and offered to help with the next sounding.

Not that there was a next sounding. We’d been sort of lucky to even be able to claim this as a deployment – our supercell actually managed to put down a grungy tornado at 6:09 pm, just three minutes after the first lidar data came streaming back in. A look at the sounding from our spot tells the whole story:

And no, there was not a chance of seeing the tornado that was ongoing 25-30 miles away from our spot.

Too far away to see, just close enough and just fast enough to collect data – it was not exactly a banner day for the lidar vehicle. And for everyone else, who had followed supercell number one further and needed to backtrack more to supercell number two, it was even more of a wash. Outflow undercut the circulation shortly after the brief tornado and effectively ended the tornado threat on the Llano for the day. We stayed at it for another half an hour until 6:53 – after all, what was the real rush? – but it was obviously going to be a null dataset with the storm rapidly moving away. In the hierarchy of the insane, record-breaking 2019 tornado outbreak sequence, there’s a reason nobody remembers what happened on May 25.

By this point, the great Memorial Day Weekend role swap was fully underway. The far-field vehicle pulled up to our intersection, and Liz and Manda commandeered the support vehicle to head back to their wedding. In the meantime, the sun came out for the first time in literally days, breaking through the smoky stratus in what felt like a cleansing moment.

The storms on this day had added even more rain to the already-soggy roadways across west Texas. Thus, the drive back to Amarillo was one long progression of zooming by flooded-out fields, over sodden ridges, and then through flooded-out washes that tempted the old lidar truck to hydroplane. Mike told me to slow down multiple times, which I probably should have listened to, but I just desperately wanted to get back to Amarillo to finish off a brutally long day of driving. We both heaved a huge sigh of relief when we got back to the little string of hotels along I-40 for the third night in a row.

The night had one final surprise in store for us, in the form of an EF-3 tornado that occurred just west of our homes in El Reno that evening. It was embedded within a line of storms that had grown upscale from our original supercell and wasn’t deployable, but it was not exactly a great feeling to watch RadarScope as the line overtook our hometown with a bunch of scalloped mesovortices all while we sat at a Nolan Ryan’s steakhouse 400 miles away. Unfortunately, the El Reno tornado was a killer one. It was a downer way to end May 25.

After 4 straight days on the road, I was officially out of clothes (I was actually way out of clothes. I’d thought we’d end May 22 at home instead of going to Elk City that night, so I only had one or two changes). What was more, the end was nowhere near in sight. While the 24th and 25th had been relatively lackluster days, things were going to heat back up on the High Plains. Memorial Day weekend was starting off with a bang – and it was time to head to the state where chaser dreams die. Colorado awaited.