I tried to do a TORUS diary like I did last summer in San Diego, and it turned out that long days of fieldwork proved not to be conducive to a diary series. So instead, I’m just going to write a quick recap of a hectic two weeks. The bottom line: with the storms largely being uncooperative, I found my memories from the TORUS 22 project in the non-storm moments.

When I wrote the setup to the project, I was sitting in Salina, writing that the next day would be marginal somewhere in Kansas or Nebraska. That turned out to be correct and fit a theme of setups that we probably could have skipped but chose to chase out of desperation. A quick summary of the events:

- May 17: we headed north on US-81 toward Belleville, Kansas with the hopes that a storm could maintain supercellular characteristics along a weak frontal boundary. The storm did not maintain any characteristics.

After sunset, a nasty MCS developed to our northwest and dove into the Salina area. I was outside doing some nocturnal shelf photography and was pretty happy with how it went:

- May 18: Gave up on a possible target in southeast Colorado due to marginal everything. Decided to hedge on a possible deployment the next day along the Minnesota-Iowa border by driving from Salina to Council Bluffs, Iowa. Colorado did not do any supercells, but there was a haboob which is cool.

- May 19:Woke up early and booked it toward Albert Lea, where a warm front was expected to cook all day and have a powerful supercell along it later in the evening. By mid-morning, supercells developed north of the warm front along the Iowa-Minnesota border, reinforcing the cool side of the front and developing a sharp boundary. Meanwhile, the environment south of the front mixed due to poor moisture-quality, so that by CI time things were not looking great.

The result was a mushy mess of storm updrafts along the boundary, none of which were targetable. I was in my first deployment directing NOXP, and, due to my own hubris, the far-field team, and failed miserably in directing those two vehicles plus my own. Eventually, we ended up south of an outflow-dominant complex of storms near Austin, Minnesota which at least looked pretty and did some turbulent cloud structure things. We ended the night watching an updraft near Mason City, Iowa.

All in all, I hate Minnesota.

- May 20: Down day to drive back to Norman.

- May 21: Down day in Norman.

- May 22: Down day once more, positioning in Amarillo to be ready for the potential for supercells on the High Plains the next day.

- May 23: Probably the only useful day of field research of the entire May 2022 TORUS session. It was a “go here, dummy” kind of target with a surging warm front across the West Texas Plains. If you see 60 dewpoints with surface southeasterlies west of I-27, you should prepare for Large Ones. I found myself to be one of the few optimists early in the day, but sitting west of Lubbock, with the sun coming out and cooking the boundary, others began to share my optimism. By contrast, I had a migraine by this point that very nearly derailed the day.

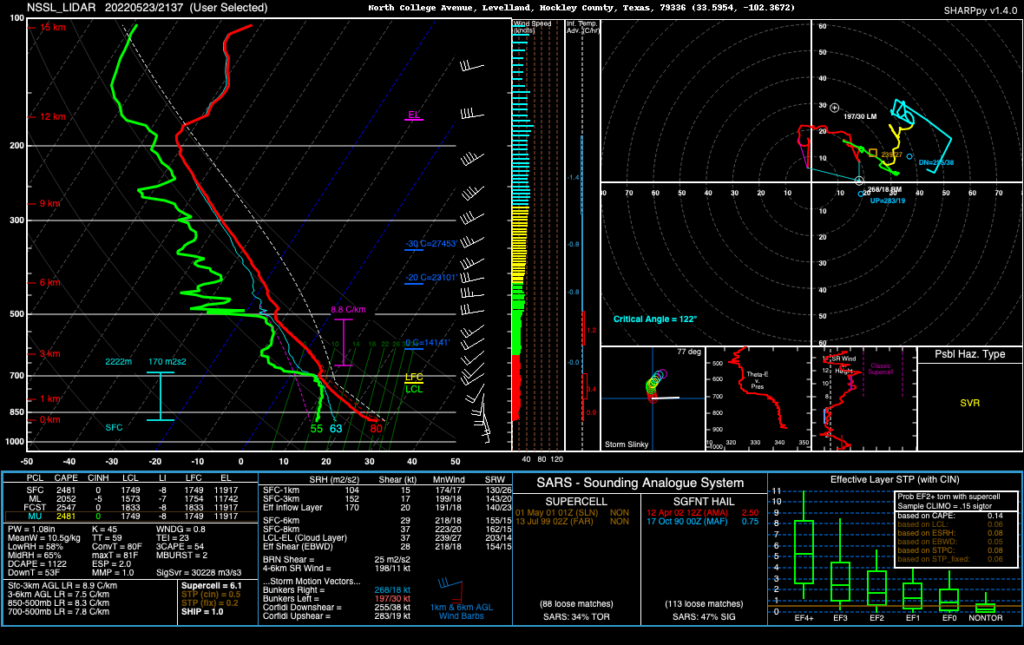

That sounding, from Levelland, confirmed to me that we were about to have some Big Ones as long as an outflow boundary flying up from convection to the south didn’t affect thermodynamics too much. It seemed touch and go for a while. We sat north of Morton, with NOXP scanning on updrafts developing north and west of town.

The storms gradually closed on our location, with updrafts congealing and merging and generally just doing weird things. There was a dominant meso in the middle of the mess, but gradually an updraft to the south began to develop supercellular characteristics. The only problem? Here came the boundary, screaming in:

All the while, NOXP scanned. If I rolled down the window of scout, dust got everywhere, including in my teeth. The good news? Visibility was near zero, but I could make out the markings of a powerful meso developing pretty much right in front of us.

And then the galling moment: Tony and Don redeployed NOXP to the east. Behind us, the storm became a mammoth that would ultimate produce 8 tornadoes. Some of them were highly photogenic. Some of them could be seen at the same time as others. And some of them were pure, mean wedges. But… all I saw was a radar screen and a wall of dust.

I’m not going to link the closer views of the tornado. There’s no point in rehashing that, right? Instead, just know that Mike, Wenjun and I seethed while TORUS scored a big one like it was 2019. I heard stories of radars taking RHIs through tornadoes and other crazy shit like that. When sun set and the deployment was called off, the supercell was still looming like a mammoth wall of cloud in the distance. It was one of those storms that just makes you feel small. We had time to do a little bit of lightning photography on the way back to Lubbock.

- May 24: A cold front swept south of Lubbock, limiting TORUS operations latitudinally. The post-frontal airmass was unstable enough to support supercells, although just how tornadic they would be was very much in question. Operations began early in the afternoon as a thunderstorm developed right over the staging point in Hobbs, New Mexico and headed southeast into the Permian Basin. From my guest spot in the far-field sounding vehicle, I directed a sounding from Hobbs as the storm developed, then another along a dried-up lake bed northwest of Andrews as updrafts were consolidating (the first balloon popped when it blew in Wenjun’s hand and hit scrub brush).

The storm surged southeastward as some sort of probably-supercell. We kept positioning ahead of it (although not as far ahead as we should have been), and set up for another sounding north of Midland. At this point, the storm was at its peak, with a powerful (albeit elongated) updraft base and a rock-solid mid-level meso.

Unfortunately for TORUS, the storm went outflow-dominant, surged out and dove due south into Midland itself before all vehicles could reposition. Midland rush-hour traffic scraped us out of the chase, and that was that. Far-field managed to get to the other side of Midland in time to see an underwhelming haboob and to slide east and north ahead of the heavy precip. We had a long, stratiform-y drive back to Lubbock.

- May 25 – Drove back to Norman.

- May 26 – Down day.

- May 27 – Drove to North Platte to be ready for a marginal setup somewhere between I-80 and I-90 the next day.

- May 28 – After a long briefing debate, punted on operations for the day. Instead, drove to Norfolk, Nebraska to be ready for the next day.

- May 29 – The day of my weather briefing, which turned out to be a big hit among a certain demographic of briefing viewers:

It turned out that Scipio would have been angry at just about all of the targets. My personal preference was to play a pseudo-triple-point located in northeastern Nebraska, not at all far from Norfolk. The other option would have been to venture further west back into the Sandhills, where a decent postfrontal supercell environment existed. The final option, alluded to above, was in Minnesota and therefore could be easily discounted.

So we sat in Osmond, Nebraska all day. Something died inside our car’s air vents, and we got the scent of “dead fish jerky” in the middle of NOXP scout for just an unfortunately long time before it went away. Then we realized that the car was super overdue for an oil change, and out of an abundance of caution and fear for what would happen if it didn’t get changed, we headed up to Yankton, South Dakota to get it changed. Nothing was open that late on Memorial Day, but it didn’t matter. Cloud cover had moved in and killed the exciting triple point target. Whomp whomp. Right around sunset, there was a monster supercell in the Sandhills, but that’s not something that you think of wistfully in my opinion. Overnight, that supercell congealed with other updrafts to form a nasty bow echo that rocked right through our Courtyard Marriott in Sioux Falls. This apparently included a tornado that only narrowly missed the hotel. I was knocked out from exhaustion and never heard it, but plenty of other team members heard the building groaning. We woke up the next morning to a wide swath of damage across eastern South Dakota on:

- May 30: My last ever day of fieldwork operations. I wanted to go out with a bang so, so badly, and there was at least a chance of doing so. A moderate risk was in place for severe weather, with the specific risk mentioning strong and long-track tornadoes across the risk area. The problem? We were going back into Minnesota. And as I said before, Minnesota bad. There actually was a secondary play somewhere in eastern Kansas that verified with some decently structured HP supercells. It would have been a hell of a lot shorter drive home than Minnesota. And yet, nobody could turn down the moderate risk.

It was sort of a logistical nightmare as well. Storms in Minnesota were expected to move somewhere in the range of 45-55 knots, meaning that TORUS was gonna get one swing at the plate on whatever they targeted. To add to my anticipation, a week-plus of lobbying by me was finally paying off – I’d been added to the roster in Mobile Mesonet 2 with Erik, Lauren and Dean. This was a true honor and excitement – my last mission, my first near-storm mission.

We set up in southwest Minnesota near the town of Tyler. It was here that I got to see the world’s smallest (maybe not, but at 2 square miles, still pretty small) National Wildlife Refuge Unit.

Pretty quickly, it became clear to me and everyone else in P2 that things were unraveling. Convection developed in eastern South Dakota as a messy blob, and when an outflow boundary started to push east it became clear – this was going to be a QLCS washout. We made the most of the QLCS as it approached Tyler, running transects on the outflow boundary for funsies.

The best we could claim to do was be near a little nub of a mesovortex just to our southeast.

It was once again a very long drive home from Minnesota.

The theme of TORUS 2022 weather-wise was for expectations to be shattered, for mileage to be added, and for a lot of hedging for the next day or event. Honestly, it sucked. I won’t look back on the project and remember the fun storm chases I had, unlike 2019. This time I’ll remember it for the memories I made not in operations, which hopefully I’ll get to in a future blog post.