Hopefully the first six months you have at a new job aren’t an omen. If they are, then NWS Norman is in for a ride over the next however long I work here. I’d already seen some wild stuff *before* last week. I was in the office way back on November 5 working TAFs as a legitimate cold-season outbreak sent the first violent tornado into Oklahoma since 2016 down around Idabel. A month later, we got a legitimate mini-outbreak of QLCS/embedded supercell tornadoes in the middle of the night, including an EF-2 that hit the town of Wayne. Of course that occurred in the middle of a mid-shift for me and led to some memorable moments on the social media desk:

A week later, I was out in the cold – literally – as we had one of our coldest stretches ever just in time for me to get to do some morning soundings.

Fire hotspots, an extremely weird winter storm in January, the Chinese spy balloon craze, heat waves and drought, and just an obscene amount of cold season tornadoes – I legitimately thought I had seen all that the Southern Plains could throw at us in my first six months. My time at the Radar Applications Course in Norman came in mid-February. Hopefully things would progress slowly after I got out of RAC and allow for some easing into severe weather operations, maybe give me a chance to issue a low-stress first warning of my career.

Welp.

Let’s walk through the wildest week of my young career, as seen through the lens of 3 specific days.

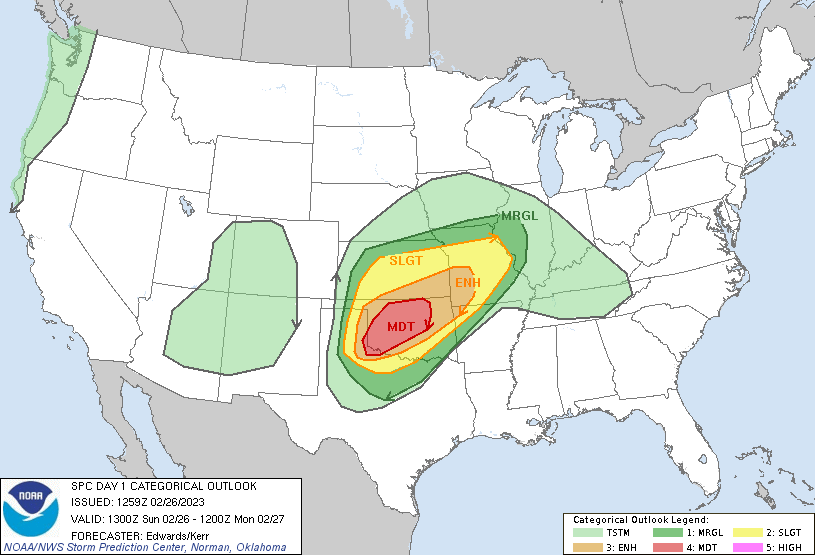

Sunday, February 26

Sunday, February 26 looked like trouble to me as far as a week out while I was still in Colorado with family to prep for wedding stuff. Models were incredibly consistent showing a near-perfect trough ejection over the Southern Plains on the evening of the 26th. The main question was how much moisture we could sneak up into the area where height falls/temperatures aloft would be coldest before CI. Some models suggested low-60s dewpoints. The NAM, mired in shallow-cold-airmass mode from a midweek cold front (that it nailed) was a lot less impressed. As always, truth was somewhere in the middle. While we probably wouldn’t have enough moisture for widespread discrete daytime supercells, my assumption was that an eastward-racing Pacific front was going to encounter enough instability and favorable profiles for VERY damaging winds and possibly some tornadoes.

The event was very poorly-timed from a staffing perspective. Two lead forecasters were on annual leave, while a third was sick. A general forecaster was on vacation out of state. Rick and Vivek were in Durant with an emergency manager conference. Forrest was at a wedding And just like that, our usual staff of 20 or so people who could handle operational tasks was down to 14 on Sunday. Every single person who could come in at a certain point was asked to do so. It was an all-hands-on-deck situation.

My hands were due on deck at 5:00 p.m. as the event was forecast to get underway in the eastern Texas panhandle. Erin scheduled me to work social media and short-term watch-to-warning graphics through the event. A day or two before, I had come down with a nasty cough that really threw me for a loop. Whether it was allergies or a cold, there was no way I was missing this event. Why would you work for NWS Norman if you ducked out on a potentially high-impact derecho?

When I arrived, storms were beginning to fire right on schedule. Every workstation was full from the warning mets to a WDTD employee (Jill was filing LSRs) to my workstation in the far southwest corner, which I shared with our undergraduate volunteer, Matthew, as I walked him through the office mantra for severe social media. I showed him how to retweet the automated warnings that pop up on a bot. I also showed him how to (and how often to) post a short video with a radar loop to our Twitter to keep up the stream of info. Little did I know that soon I’d be overwhelmed by everything else that had to be done and Matthew would be posting radar gifs onto social media on his own.

The event started tame enough – storms gradually upticked and became severe in the panhandles like I’d expected, and storm chasers were getting treated to jack squat from it. The storms were a bit more cellular than I expected, and they were certainly racing eastward, but they looked meh.

And then just like that, there were supercells threatening to produce tornadoes right over I-40 in the panhandle. This was a theme of an extremely fast-evolving event: blink, and things would change on you. After getting the go-ahead from Mark, I got started on my first-ever watch-to-warning graphic.

Verification: Cheyenne would get hit by an EF-2 tornado around 7:15, producing our only fatality of the event. An hour and 15 minutes isn’t bad lead time, though, given the vulnerabilities of the area.

The event continued to unfold rapidly from there. The Pacific front swung into the backside of the loosely organized storms and forced up a nice, steady squall line south of I-40. I got started on another graphic highlighting “significant damaging winds to 80 mph”. As I was finishing up, someone announced in an awed voice that a West Texas Mesonet site had just received a wind gust to 114 mph. Without breaking stride, I went back and changed “significant 80” to “destructive 90” mph.

Other than somewhat slow graphic generation, Matthew and I were rocking and rolling. The squall line very immediately announced that it was NOT going to behave, rolling over the town of Willow with a pronounced embedded supercell and mesocyclone. That wasn’t the only one, either – Ryan and Jennifer clearly had their work cut out for them as warning forecasters.

To add to my hectic evening, as the line began approaching the population centers of Oklahoma and western north Texas, the phone began ringing off the hook. Some of the calls were people asking what the weather was going to be like. Some had storm-specific questions. Others provided a certain level of comedic relief, like the spotter in Lawton who reported 70 mph winds and no damage near downtown. And others were emergency managers trying to do their jobs as best they could, asking about how long they should sound the sirens for. Nobody else seemed super inclined to pick up the phones, which is how me and my bum throat ended up taking hundreds of calls in one night. It was a Jordan flu game performance even to talk that much.

Not that the social media became any easier. Every minute or two there was a new warning to concern myself with tweeting out. We tried to come up with messaging to fit such a dangerous storm system on the fly, and I settled on “treat all severe warnings like tornado warnings tonight”. It was also just a struggle to maintain situational awareness given everything else going on. I had to stop for a minute, take a deep breath, and evaluate radar before my next watch-to-warning graphic.

Well that was unpleasant to look at. On top of the fact that the squall line was nasty and reaching ever-further north with potentially tornadic couplets, a feature caught my eye over eastern Kiowa and northwestern Comanche Counties. It was a sort of embedded bow feature within the QLCS, but to me it looked more like an embedded supercell. And it looked like an embedded supercell that meant business. While many other parts of the line were seeing quick-occluding circulatons that led to the dreaded “candy-cane of death” where the tornado hung on the backside of the squall line, this embedded supercell didn’t do that. It just… hung out. And if I projected its path out, I didn’t like where it was going. In fact, if there was ever a time to invent a two-color-tiered watch-to-warning graphic, now was it.

Spoiler alert: that would verify quite well.

There was a sort of a lull as the northern part of the line quieted down and only one candy cane really brought itself to bear in Caddo County. Maybe the instability was running out as we got to the east side of the warm sector. We hadn’t seen any crazy winds in the last hour. Maybe we could escape without things getting too bad?

No sooner had I thought that than all hell broke loose. There was a tornado debris signature near Minco, heading toward Union City. Enid was under a tornado warning. Another possible tornado was near the KVNX radar and heading towards the Kansas border. Callers were ringing me off the hook; my voice kept growing more hoarse. Our warnings could barely keep up. And when I looked southwest toward Chickasha and Blanchard, I *really* didn’t like what I saw.

I wish I could tell you that I’d had time to really acknowledge that Norman was directly under the gun. And in a sense, I had. I’d called Elizabeth at 7:45 and told her to put the harness on the dog and start gathering things she couldn’t live without. I’d told her specifically that I thought south Norman was under the gun and to let our friends at The Links know. But maybe I hadn’t had time to stop and think that I was working in south Norman. It’d be hard to blame me; Matthew and I were cranking out social media updates as fast as possible. Still, I stole a quick look at radar and saw a clear couplet on the south side of that supercell near Cole, moving northeastward towards Goldsby, I-35, and Highway 9. Just as I had time to wonder whether we should pull the trigger, Alex picked up the office walkie-talkie and called NWC security. “How are you guys doing?” he asked. “We’re just getting ready to put the building in a warning.”

NWC security acknowledged his statement. Moments later, the building sirens began wailing, encouraging people to shelter on the first floor. I called Elizabeth for a grand total of 14 seconds just as the warning was issued. She acknowledged that the warning had already gotten to her and she and Scipio were sheltering the kitchen. I had just enough time to tell her that I thought it would miss but please to let her friends at The Links know to take cover. And then I hung back up to answer the office phone.

NWS offices have backup plans in place in case they need to drop operations to shelter during severe weather, or if there are power issues, or any number of other things. This was never discussed here. Maybe it’s because we only had bare minutes from warning issuance to the moment of possible impact. Maybe it’s because we had so much else going on that to stop and debate whether we needed to shelter would put us impossibly behind on the warnings. And maybe there’s just an old-school “stay at your post” mentality at NWS Norman that no mere QLCS tornado was going to take away. But next thing I knew, I was looking at radar in a quiet operations area and muttering “Shit” into the silence every 15 or so seconds. Mark quietly got up and lowered the blinds to the windows, presumably to keep me in my near-window seat from being gutted like a fish by flying debris.

Still I rationalized in my mind. Shouldn’t the storm be here? I guess there wasn’t really a tornado. The thunder had only really begun to increase in the last few minutes. Now rain began to lash the windows outside. The wind increased from a creaky rumble outside to a whistle, which increased to a howl, which increased to a pure scream. Sitting there on the phone with the the EM in Newkirk, I kept one ear out the window.

There was a commotion in the breakroom as three SPC forecasters ran… giggling? and wrenched the door open. The sound of the devil’s scream outside became that much louder as they hooted and hollered. On the other side of ops, Ryan and Jennifer calmly stated that their ears were popping. A moment later, my ears popped too. Max reported that the power had just gone out on Jenkins outside. Mere seconds later, the power in the building flickered as the lights went to backup generators. In disbelief, I realized that we were inside a tornado.

We actually weren’t. Unbeknownst to me, an EF-2 tornado was passing about a half mile to our south. But still, it was close enough to hear it and feel it, and it was deeply unnerving. The most unnerving part of it all? The pure lack of acknowledgment of the predicament all of us were in. All of us just kept doing our jobs because someone else out there was going to be in a worse spot than us, and we owed it to them to keep them safe.

Mere minutes later, damage reports began to trickle in from just down the road at Highway 9 and 12th Avenue. Further reports would come in of rather severe damage to apartments, businesses, and homes in southeast Norman. Lauren called Max at one point in a clearly distraught manner to tell him that her house had been damaged. It was clear that this was going to be an emotional toll for a lot of people. As for us… business went on.

As soon as the Norman tornado dissipated, the supercell produced another one along I-40 near Shawnee which went on to produce some severe damage of its own. Elsewhere, though, it looked like the line was winding down. My adrenaline was still pumping in overtime mode. When John asked to go home to check out the damage at his house, I offered to cover the 06Z TAFs for him and passed what remained of the social media work to Matthew and Alex for the night. I filled out the most bullshitted set of TAFs in history, then at Erin’s insistence, I went home. Elizabeth was also clearly shaken by her experience home alone. Try as I did that night, I couldn’t find it in me to be emotionally shaken by my close call. I couldn’t even figure out the reason why. Was it still too soon? Too much adrenaline? Was I just numb to tornado dangers? To this day, I couldn’t tell you. More than anything, I was just relieved to collapse into bed and get some sleep before starting my actual workweek the next day.

Tuesday, February 28

The world’s weirdest workweek continued on Monday, when I was pretty much given free reign to do what needed to be done with the day forecast. Given the extensive damage, Mark and Todd were pretty much completely focused on getting damage survey teams out to the nearby tornado spots. Three different teams including a few WDTD employees surveyed the Norman tornado alone, while others headed to Mustang and Shawnee. The rest of us including Mark, Todd, and myself had a flat-out day in operations plotting damage tracks, talking to the media, and reviewing possible tornado locations. I had the distinction of being the day shift forecaster and had never had such freedom to do what I wanted. And I mean that. It came time to issue headlines and everyone signed off on a red flag warning for northwest Oklahoma without so much as a peep. Right before leaving, I asked Mark if I could come in to help with surveys the next day. He certainly wasn’t going to say no to a volunteer.

There was nowhere near the same amount of manpower to continue surveys the next day. Todd, Phil, and myself had the unenviable task of trying to survey the entirety of western Oklahoma within one Tuesday. We had to split up somehow, and given the fact that the worst damage we knew of (and the fatality) was in Cheyenne, it made sense for Todd and Phil to head out there. For a while, I thought I was literally going to be driving out somewhere on my own, but at the last second someone got a hold of Forrest, who had just returned from the funeral he was at in Dodge City. Unfortunately, Forrest lived on the other side of the Norman damage path as the NWC. He couldn’t get in to the office until close to noon. With the best will in the world, he and I couldn’t survey the three areas Mark had assigned for us in one day. As a weird sort of pseudo-mission-lead, my strategy was simple: we should drive all the way out on I-40 to the furthest damage path near Willow and work our way back down Highway 9.

My first-ever damage survey! This was exciting. Maybe a little nerve-wracking, too; nobody had ever really shown me how to use the iPad with the software that lets you log damage to DAT. And I could probably conservatively be considered “underqualified” for the job I was doing. “Underqualified” in the sense that I haven’t really gotten any formal damage survey training, and I certainly hadn’t ridden along with any. To be honest, this was not as much of a problem as it seems. Nowadays, a surveyor can head out to the damage spot, take some pictures, and put in a suggested value at each DI. Then someone with more experience (Doug, in our office) can sort through what the *actual* value should be.

Only one problem in Willow. When Forrest and I got to town and started driving through the early reaches of the damage path, we found absolutely nothing. I think the only damage report we’d received from the area was a barn damaged 3 miles south of Brinkman. Forrest called his observer down in the area, who relayed the same thing. We went down dirt roads to the intersection 3 miles south of Brinkman (which is basically just a cemetary), and then fanned out from there. Nothing. We went northeast of Willow on the other side of the highway where the possible tornado track intersected some trees. Still nothing. Finally, after an hour we had to give up.

You can imagine how this felt for me. My first damage survey, I’d been given a pretty good deal of responsibility for something we were considering a probable/likely tornado, and I shot a blank. Rationally, this was one of those things that happen. Willow is an extremely small town that our expected track mostly missed. The tornado would have passed through a hell of a lot of farmland and not much else. And who was to say whether there actually was a tornado down there embedded in the wind and darkness anyway? Yeah, rationally I knew it wasn’t a black mark against me. But rationality was a little hard to come by as Forrest drove across to Highway 6 and then Highway 9 to start in on our next track.

This time, I was confident (praying) that we would find damage. I *knew* there had been a tornado in the track Doug had outlined from just southeast of Lone Wolf to northwest of Hobart. TV chasers had seen it, and I’d seen pictures of damage tweeted at us from near Hobart. So in the back of my mind I was at least sure that if we didn’t find anything, I’d know it was all my fault. Which was sort of a consolation, in a way.

Our first few transects of the possible damage path didn’t turn anything up. Just as I was starting to worry, we reached a dirt road intersection and Forrest started to pull up short with the Co-Op van. I couldn’t tell why at first. Then he pointed it out – the stop sign had been straight up sheared off at the base. With his fancy rolling measuring tape, we quickly learned that the stop sign had been thrown 70 yards away from where it was supposed to be standing. And we were right where the tornado was supposed to be. My first damage survey was on!

Forrest and I zig-zagged northeastward over the Kiowa County grid for the next two hours with under the late winter sun. There was a lot of open farmland that the tornado passed over, but every once in a while a tantalizing clue appeared. Several dilapidated farm outbuildings destroyed. A single healthy mesquite tree along the side of Highway 9, snapped off near the base with buds still growing on the branches. And sheet model thrown, rolled, and chucked across all of the shocking-green fields of wheat. Each time, I reset the DAT app on the iPad to make sure my location was correct when I logged back in (it’s a weird bug), took a picture, and then made a very best estimate as to what kind of winds would have done it. And there were conflicting clues! A mesquite getting snapped off is pretty impressive, but on the north side of the highway a very broken down shed was left mostly standing. 100 mph winds, maybe?

The best clue we were going to get was a farm at the intersection of Highway 44 and CR 1380. On the northwest side of the intersection, a home sat with 2 outbuildings amid a stand of larger trees, while a larger stand of hardwoods was on the northeast side of the intersection. At first glance, the home seemed largely intact, although it had suffered some minor damage. There was debris strewn about their yard. Behind it, a barn had had the roof pretty much entirely removed and walls were collapsed. It looked well-built, but had an opening on the southern side. I navigated through the DAT and tried to guess the winds that would have done all this. 90 mph?

I didn’t take any pictures of the trees behind me, because the family was actively cleaning up and Forrest was adamant that we didn’t want to disturb anyone. They weren’t snapped like the mesquite, but some large, thick trees were sheared off in the middle, branches were strewn about, and somebody’s entire life was deposited within that stand. On the southeast side of the intersection, the power company had already replaced all of the poles, but the old ones that had been tipped over were left to see. One was noticeably shorter – snapped off near the base, I presume. A theory formed in my head that the tornado had been on the wider side to catch the entire intersection, but the stronger winds had just barely missed the farm. Based on the tree and pole damage, I logged a damage indicator of 110 mph, my highest of the survey. All of the damage kinda jived with “high-end EF1” in my mind, but not with a massive degree of confidence.

We continued on past the farm for several more miles, noting a more or less continuous track of thrown sheet metal, tree branches downed, and power poles being tilted over as the path contracted in width. Finally, we reached the end of Doug’s possible track and called it. My first damage survey (with a major assist from Forrest) was over.

There was one more area of damage between Albert and Binger that we were supposed to look through. However, by the time we arrived in the area, it was 6:00 and the late winter sun was fully setting. The two of us decided to pass on a twilight survey in favor of coming home. Hopefully the work we did out by Lone Wolf-Hobart would be enough to hold our heads high. Mentally, I added the note that “hopefully the survey made any sense whatsoever”.

Doug took a look at the tornado a night or two later. Although he didn’t use the 110 mph max wind that I had suggested, he did rate the tornado EF-1 based on our pictures/reports and officially put the maximum winds of 100-105 mph. That’s not too bad for a first-ever survey.

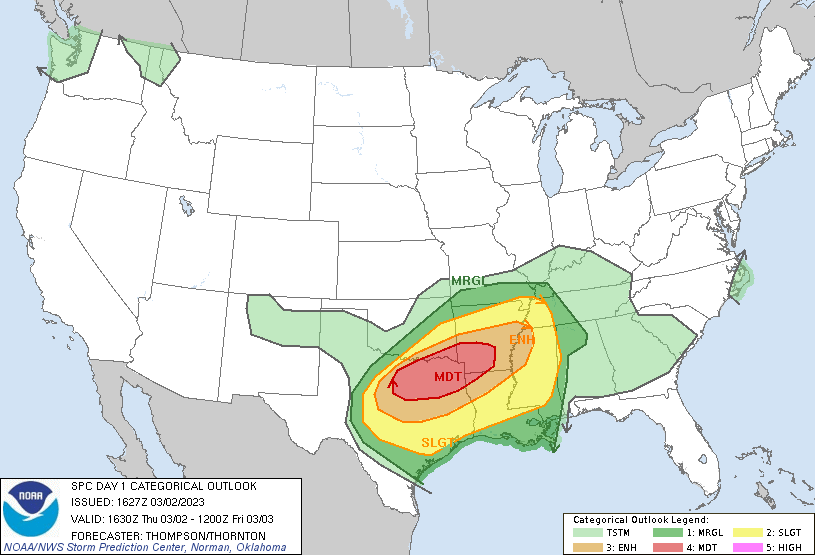

Thursday, March 2

In a week of firsts, why not throw one more out there? Maybe I was a little frazzled by Wednesday afternoon from the previous 3 days, but the weather was leaving no room for the weary. There was another severe risk lined up for the next day, this time centered in our southeastern Oklahoma counties. Given that I was freshly out of RAC, Todd thought it would be a good idea to take advantage of a weekday event to let me get some experience sitting in with the warning desk. In a doubly helpful fashion, the weather seemed to be promising an early round of elevated thunderstorms north of the warm front that we could get some low-stress warning experience on. Erin asked me to come in at 8:00 to do that, then switch over to short-term graphics. Sure, I can do that!

Only one problem when I arrived at 8:00 the next morning – that round of storms was largely failing to materialize. Todd set up a workstation for us to work from together to warn some storms, but all the atmosphere seemed willing to give us was a bunch of boring old slop. He popped in and out of his office when needed to issue significant weather advisories on the stronger cores, but otherwise we were kind of watching and waiting.

Before surface-based convection reached our area from western north Texas, the two of us were due to shift primary warning duties over to Phil. But by that point, all we had to speak for was one sort-of-forced warning in western north Texas for marginal hail over Wichita Falls that had only managed to produce peas. So Todd asked Phil if we could take warning duties a little longer as two supercells made their way out of the north DFW metro toward the Red River.

I’d gotten the chance to issue an SVS on that piddly little Wichita Falls storm. This was going to be a bigger deal than that. Everything in my meteorological toolbox that I knew was screaming that this storm was producing some pretty big hail, and Todd was letting me into the driver’s seat to issue the warning. As the storm approached Lake Texoma I started drawing up a warning polygon for parts of Marshall and Bryan Counties. Todd and Ryan Bunker watched intently over my shoulder and offered suggestions – flare it out more, 2 inch hail potentially, add eastern Love County just to be safe. To be honest, it felt like a “cooks in the kitchen” kind of moment. Finally, I was ready to press send. 25 years of my life had, in a very real way, all been leading up to this moment.

Almost instantly, the storm’s hail core began to weaken even before the storm crossed the state line. That’s just how it goes. Clearly I wasn’t going to verify my “considerable” tag for hail, but I might still get severe hail or damaging wind gusts.

And, in fact, we got both. While the storm was crossing the Red River, the hail core may have begun to collapse, but the supercell encountered a zone of weak easterly surface winds within the warm frontal zone. It developed a rather strong mid-level mesocyclone. Of course, in the very last week of our Durant radar gap I was stuck looking at velocity at 11,000 feet above the ground, but the meso was rather tight and persistent. Todd happened to be in the warning chair at the time, and he drew up a tornado warning. We agonized over it for a couple of minutes before he let it fly.

Of course, we never will know exactly what was happening in the lower levels on March 2. We did get reports of wind damage and wind-driven hail down in Marshall County, so that’s a good verification of my original warning (lead time of 37 minutes!). Did we make the right call in issuing a tornado warning for Bryan County? Did we not? I don’t know the answer to that question, to be honest.

I stayed at the office until 6:00 that day to help generate graphics for a flash flood threat in southeast Oklahoma. And then, exhausted from my 3rd day of overtime out of the last five, I slunk out the door. When I’d walked in, I was a meteorological rookie. Now, I was an experienced warning forecaster.

Conclusion

I had to grow up as a forecaster during the past week, and I had to grow up fast. I’m so fortunate to work with an incredibly talented team who can help me grow in each task. Our CWA is lucky to have them to keep them safe so that I don’t always have to. Sooner or later, the activities of the past week will feel like they’re just part of the job description. But for now, to this novice, it was a formative learning experience.