For the first time since May 18 (and the first of many days in a row), I awoke on May 23, 2019 in a hotel room. The TORUS campaign had had some incredible highs on May 17, and some of the lowest lows in the historic May 20 and 22 busts. The latter two were weighing on everyone’s mind and ingrained a sense of cynicism into the weary scientists on the research mission in Elk City. Still, there was a solid chance of more severe weather on May 23, and we were going to give it a go.

The background synoptics were essentially unchanged from the last few days. There was a large closed low over the western U.S, with embedded waves in the flow responsible for kicking off round after round of convection along and north of the quasi-stationary surface front wherever it happened to be at that moment.

Somewhere along and south of that boundary, if it didn’t sink too hard like it had 3 days ago, the dryline would mix eastward later in the day and a juicy severe environment would form along the triple point. Now, look, I am writing this in 2022, which means two things:

- My memories of this campaign are starting to get fuzzy, which, well, it happens.

- I’m a much, much better storm chaser now than I was in 2019. There are probably patterns I would recognize now (coming off of high-success-rate years in 2020 and 2021) that 2019 Nolan just didn’t get. If anything, I probably feared the triple point after watching the boundary undercut us 3 days ago.

I was wrong often during TORUS, but never more so than on this day.

The first order of business was definitely unobjectionable: get somewhere out into the eastern Texas panhandle to be in place for Caprock Magic. The luxury of staying in Elk City was that we could position more or less at our leisure – the planned congregation of all TORUS teams in McLean, Texas was only an hour away. So it would be an easy morning drive for myself, although we were all dissatisfied to see the continued morass of smoke and low clouds streaming northward under the persistent low-level southerlies. My kingdom for a clear blue sky.

In looking for the restaurant we stopped at in McLean, I just learned something new – that there actually is really one real restaurant in town. Guess that makes the search easier! McLean is one of those Route 66 living ghost towns, where the rolling prairies of the Caprock honestly seem to swallow up the few blocks of rundown homes and the worn-out brick downtown. You can still see the tourist-driven past of McLean reflected in the red brick of Main Street when you park in front of Chuckwagon, one of those places where everyone knows everyone who walks in 362 days a year. This was one of the odd days out, but the locals weren’t fazed – any Caprock town has to know what it looks like when the storm chasers come to town.

The staff at the Chuckwagon did an admirable job dealing with the hordes of OU/NSSL dweebs staining their booths. They fed us and fed us as fast as they could, all while the researchers kept trying to plan ahead. It was here that we got the not-entirely-welcome news that the SPC had upgraded the area to a moderate risk for the afternoon:

Bust fatigue is a thing. I distinctly recall not wanting that red blob over our heads. Couldn’t we just get a sneaky overperformer instead? With that said, the upgrade made sense, particularly with yet another volatile environment overhead:

And, in fact, for the first time that day, as lunch wound down and I ate some sort of dessert, Mike displayed the first urgency I had seen from anyone that day. He wanted to get further west prior to CI. I got behind the wheel again and we headed another 40 minutes west, through some of my favorite terrain in the entire world. The last time I had been here was 2 weeks prior on May 7, and I would presently show that the ghost of that day lived on inside of me. But for now, optimism finally started to puncture the jaded shell inside the lidar truck, fueled by breaks in the ever-present cloud cover. If we could warm enough, if the outflow boundary could stop sinking south, if we could just get a supercell to form on the warm side of the front, today could be really, really nice.

Mike directed me to get off of I-40 at the Love’s Travel Stop between Claude and Panhandle. The sun was shining more directly… which lay a spotlight on the absolute zoo the Love’s was. It turns out, having a small moderate risk zone in the best chase terrain in the world the Thursday before Memorial Day weekend can bring the maximum number of storm chasers out of the woodwork. I just wanted to get gas, and a Love’s Travel Stop is never small, but doing so required picking my way carefully through literal hordes of people sprinkled across the parking lot. I finally did get to the gas pump and had just enough time to begin fueling and jump back in the truck before I felt someone approach. The pedestrian walked right up to the window, and I cranked it open with the intention of telling them to leave us the hell alone, until at the very last second I realized it was off-duty NWS meteorologist Aaron Davis, who I had just met at the NWC a few weeks prior while he took RAC training. In my fired-up state, I think I was pretty blunt about how annoying the crowds were to us, but at least I was able to stop myself from directing my frustration directly at him. I wished him the best of luck on his chase and then I told Mike to get me the hell out of there.

A few other OU/NSSL vehicles were perched on the south side of I-40, where a VW slug bug ranch (a knockoff of the way cooler Cadillac Ranch on the other side of Amarillo) sits between two incredibly seedy motels. I parked in the unpaved-pothole strewn back lot of the Executive Inn and savored some silence. The moment of truth was approaching and if anything, the sun was now beating down on us in the way you’d expect a Panhandle dryline in late May to do. Big convective towers showed their faces. It was all beginning to feel eerily similar to May 7 to me, right down to the mesoscale discussion:

Mike started to narrow the target area more and more, and gradually began to focus on the area near that northern low pressure along the warm frontal feature. I chewed on that for a while. Surely I wasn’t the only one with qualms, because Mobile Mesonet 1 had gotten so antsy that they were literally on the other side of Amarillo, waiting for CI near Vega. I can get the frustration that comes with being part of a large field project, and wanting to not get bogged down by inertia and get to the storm too late, but I remember thinking that was a bold decision. This seemed doubly true when Mike made his decision – towers were going up to our north and east, and we were going to reposition to Pampa to play them.

I wasn’t convinced, and said so as I pulled out of the Executive Inn. “Mike, this is the first time I’m disagreeing with you this whole time.” To my eyes, the way to go was south along I-27, where convection was deepening near Lubbock. I was willing to concede that the storms were likely in weaker low-level shear, but temperature-dewpoint spreads of 85/65 on the Caprock work consistently with southerly winds. There’s just some science there. I didn’t need more proof that sagging boundaries can lead to undercut garbage, especially when the boundary is southwest-to-northeast oriented – I’d seen that on May 7 near Amarillo before playing the Tulia supercell to the south, and I’d seen that on May 20 when our initial target got undercut. But I’m a team player, and I left my disagreement with that one statement, and then I drove north toward the little town of Panhandle to turn northeast on US-60 and prepare for storms. By now, towers were percolating:

But only up towards Pampa were they visible. Beyond Pampa, the grey wall of smoke and stratus set in once more:

I drove through the sunny (and shockingly green) fields for a while until we got to Pampa. It had only been 18 days since my infamous encounter with Pampa PD, and feelings were still raw on my end. I scrupulously followed the speed limit all the way through the north part of town on State Highway 70, then sped off without a backwards glance. Somewhere off to my west, a supercell was trying to develop along the boundary, I think. But in the morass, there was nothing to see except for the highway in front of me and grey, grey skies.

Somewhere in that wall of red dots was the TORUS crew, getting ready to play whatever dominant cell came out of the group. Highway 70 drops into some of the most remote terrain east of the Rockies north of Pampa, in the region of the Canadian River Valley bounded by Pampa, Stinnett, Canadian, and Perryton. Nothing much exists between the 4 towns but mesas, buttes, hills, washes, gullies, terraces, and miles of miles of scrub brush on top of those features being consumed by cattle herds. The monotony was only eased slightly by the big, sweeping descent into the Canadian River Canyon, which seems way more impressive in my memory than it does on Google Street View. There must have been some incline involved, because while I was struggling to get the lidar truck up and over the far rim of the canyon, a black Mobile Mesonet went streaking past me – presumably, the same one that had previously been in Vega. Thus, any fears that Mobile Mesonet 1 would not be in position for a deployment on the storm cluster to our west were assuaged.

Meanwhile, that cluster was organizing. It wasn’t happening in the explosive way that you would expect from a Plains dryline in May, likely due to the lack of capping, but the storms were still developing into one or two dominant supercells. I wasn’t convinced that this looked all that interesting – from what I could tell, these storms were forming on the cool side of the boundary. And that’s usually the kiss of death, isn’t it? I’ve never seen a storm form on the cool side of a boundary and then catch up and get the warm inflow it needs. Even as recently as a month prior on April 17, I’d seen time and again that once the storm ingested cold air near the surface it was done. So I was silently driving on State Highway 70 until I reached the desolate intersection with FM 281, and then silently turning east. We had found the chaser train, but somehow that didn’t fill me with concern over my convictions. In my heart, I knew I was right that we should have gone south.

Just east of Leslie Ranch Road along FM 281 was a little gravel lot on the north side of the highway, perfect for deploying a lidar that needed to be leveled as best as I could park the truck. There was a nice flat section in the back part of the lot, where Liz got the lidar running. A dominant supercell had developed and we were in a really good spot to collect a dataset on it. It was still elongated and kidney-bean like, but it was less outflowy than it had previously looked, and if anything the supercell was trying to turn right and cross back into the moist air. And if that was the case, the environment in the northeastern Texas panhandle was nothing less than pure rocket fuel.

Mike asked me to launch a sonde before the forward flank got there. I wasn’t thrilled about the idea of climbing into a metal truck bed to launch a large balloon with cloud-to-ground lightning hiding somewhere in the murk, but sure, I’m a team player. I stepped into the bed and prepped a balloon in the gusty inflow. Put the (slow) regulator on, fill the balloon with helium, grab the sonde off of the prep pad and tie the sonde onto the balloon with a zip tie. Then cut the end of the zip tie off so it can’t pop the balloon, log the surface observations, take the balloon and send it away. A picture exists of me sending this sonde into the cloud deck, but it is lost to history as best I can tell. If I ever find it, maybe it will end up in this blog post.

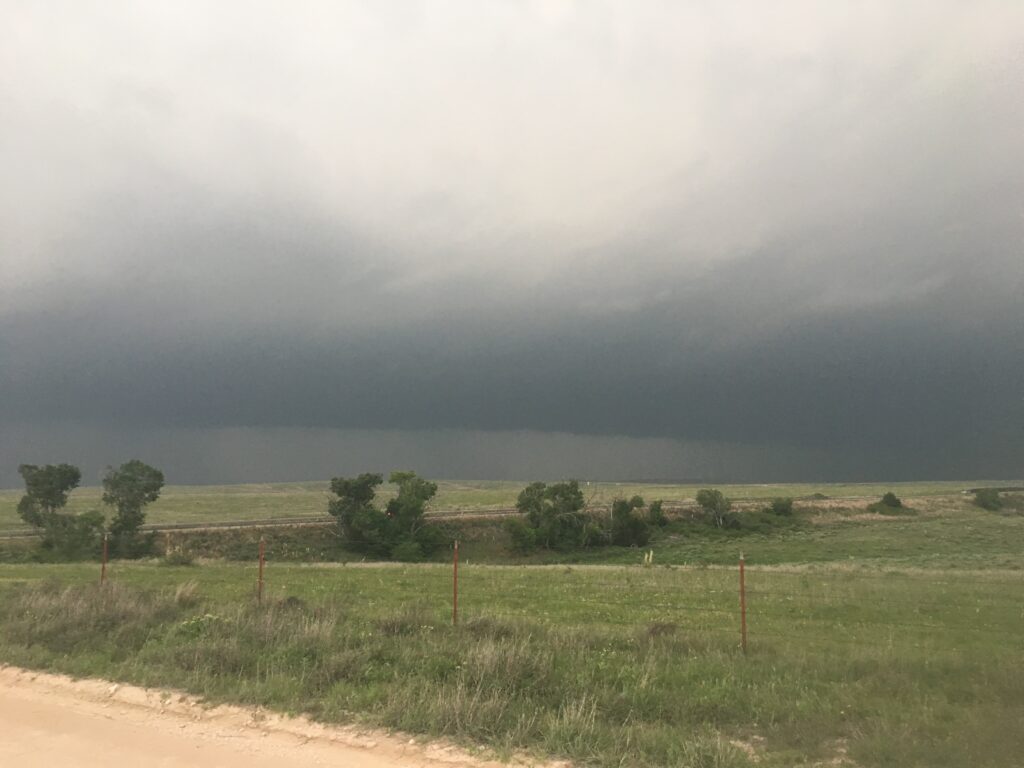

I peered through the smoke and haze and low cloud deck. The storm was now getting closer, and even had a tornado warning on it, and yet:

Brutal.

There’s just nothing you can do! No point in wondering if a tornado lurks in there, because maybe it does and maybe it doesn’t.

Meanwhile, my original lovingly created sonde had burst.

So Mike asked me to put another one in the air. Once again, I prepped it, filled it, tied it, cut it, then set down Liz’s zip tie clippers to send it away. This time, the sounding made it up into the mid-troposphere.

The only problem – the supercell was still spinning right by us toward the Oklahoma panhandle, across a woefully inadequate road network, and it still hadn’t gotten that full juice from crossing into the warm inflow. There was a new supercell developing back on its southern flank, a dangerous situation for us because it could choke the storm to its north, but also an opportunity for a redeployment. This is the kind of decision that I’m glad I didn’t have to make during TORUS. While Mike was trying to help Liz get the best lidar data possible, he was also responsible for trying to decide if this was our storm of the day, or if we needed to move. The minutes dragged by:

And finally, the PIs came to an agreement: play the next storm down. We packed up the truck and I burned rubber eastward across the Caprock.

To this point, I still didn’t think a tornado was going to happen. Call it the Smoke Hypothesis of Storm Chasing. Our FM road ended abruptly at the northwest-to-southeast-oriented US-83. At this spot, the supercell would come quite close to running us over, but Mike wanted a little bit of space. He directed me to go a mile or two southeast… and then nothing presented itself as a possible pull-off, leaving me frustrated and driving *away* from where the tornado might pass us. It wasn’t until we reached County Road 3, halfway back to the Caprock town of Canadian, that we finally found a spot to pull off that was modestly level. I turned the truck around and faced it back northwest. We were on a little ridge, so I was kind of hopeful that we could see a distant tornado, but definitely not too distant.

Unbeknownst to me, by this point a little before 7:00, our original storm had produced a moderately-long-lived EF1 north of Pampa, but nothing had come out of this tornado-warned storm. The smugness inside of me at being sure I was right about targeting was leaking out – mobile deployment teams closer to the action sounded ominously like they thought a tornado was coming. All I could do was prep yet another balloon, and pace around the truck, and wish deep in my heart that I was closer to the action.

Shortly before 7:00 p.m, Mike broke the news: Mobile Mesonet 1 was reporting a large tornado near them. Though it was no more than a few miles from us in the treeless barrens of the Caprock, we had not a prayer of seeing it.

I alternated between pacing, stewing, craning my neck at the RFD gust front to try to find the tornado:

Or just marveling at the incredible dataset we were collected in real-time. For my money, as a guy who did no tornado or supercell research with TORUS data, this was the best supercell dataset possibly ever collected. According to the damage survey, the tornado developed at 23:58 UTC, right as we were all awestruck watching the horizontal wind speed dramatically ramp up in the span of a few minutes. Those are winds under 1 km in depth going from 45 mph to well in excess of 65 over the span of a couple of minutes!

I can’t answer for what that means. Did the near-storm inflow accelerate as a mass response to a deepening of the mesocyclone’s pressure perturbation, helping trigger tornadogenesis? Or was that inflow jet already established, and we only sampled it because the we entered the inflow jet region storm was racing past us to the northeast? Or was it some combination of both? With only one lidar, I can’t say for sure. What I can say is that an inflow jet like that in the Plains with 2,500 CAPE and a fat RFD gust front could lead to a legendary monster. And this one did.

No way around it, it was a hog. It was burning me up inside to be sitting here on this patch of dirt and gravel, watching the mammoth RFD gust front, knowing that somewhere in the murk people (including Elizabeth) were seeing a truly monstrous tornado. Remember, by this point in 2019 I still had precious little in the way of tornado experience. A nocturnal bird fart by Riverwind in 2017, the distance tubes by McCook the prior week, and sporadic spoots were all I had to my name. It killed me to not be there when, for one of the first times since I moved to Oklahoma that a large tornado was present. Instead of the tornado, I just had some cacti:

And a truck:

And some cattle that looked like they didn’t want us near their pastureland that were moving ominously closer to us.

After a little while, the supercell’s miles-long RFD gust front came screaming through, bringing with it a chaotic whale’s mouth and some light precipitation. Before the drizzle fell, we collected an excellent RFD dataset, which you can see in the lidar plot above led to a massive shrinking of the cloud deck and a veering of winds to westerly. Pretty cool stuff! We waited for the sprinkles to clear out in the same spot – goodness knows we weren’t catching up to the supercell and its murky wedge, especially with no good paved options leading northeast from where we sat. In fact, this was true of almost all ground teams involved in TORUS – they got their chance, and then the storm was gone. The exception was Mobile Mesonet 1, which managed to keep up all the way until the storm reached the Oklahoma border, dropping another wedge near Laverne:

Laverne was one of the truly great wedges of the last several years. Only a precious few people saw it (including Elizabeth): many had been thrown off by the storm’s high speed, or had made my initial error and headed south from I-40 early, or had been baited by one of the other junk storms along the front. Those who managed to catch Laverne saw something special. As for myself and Team Lidar, we were in the middle of an interesting second deployment at the same spot northwest of Canadian, watching a supercell track over essentially identical ground. This one was every so slightly undercut by the outflow from its northeastern brother, so it didn’t put down another hog, but it sure looked ominously similar to how the Laverne supercell looked just prior to producing a tornado:

This time, when the outflow came washing over us, it was a signal that the day’s work was done. We stayed for another 25 minutes deployed on the cold pool as the supercell raced off to the northeast, catching a brilliant orange-on-gray Caprock Supercell Sunset while the mean cows continued to closely monitor out movements. It wasn’t until 9:00, at the end of a brutally long day, that we were done with the deployment. Liz and Mike helped me load up the sonde equipment, and we got the lidar lid closed, and then we made our weary way toward our hotel in Amarillo.

I had a long time to think about the day on the quiet, winding drive down US-60. Scientifically, the three of us had had a banner day – possibly our very best of the campaign so far. We’d had three useful deployments on three different supercells, including a fascinating tornadogenesis dataset collected no more than 6 or 7 miles from a massive wedge. So why did I feel so defeated? This was supposed to be a scientific project, not a “Nolan Sees Tornadoes” project, but the FOMO killed me inside if I let it. And, as long as the drive to our hotel was and as I tired and hungry as I was, it was hard to keep the negative away.

We got into Pampa just in time to meet some other OU researchers at the Braum’s in town. Erik and Mobile Mesonet 2 had some crazy stories to tell from near the tornado, which just let me stew quietly even more. To add insult to injury, some collapsing updrafts in the region led to one of the most intense dust storms I’ve ever seen:

Which just made the lonely drive down US-60 even more of a struggle for my exhausted self.

Finally, with the clock approaching midnight, I got us to the Courtyard Marriott on the west side of Amarillo. The hotel was abuzz with NSSL researchers thrilled at what they’d seen and collected that day. Elizabeth recounted all of the intense moments she had gone through in the brief couple of minutes we got to talk to each other before bed. Her pictures of the tornadoes were bonkers. The data I showed her from our deployment was pretty bonkers too. After we’d both agreed that the other had had a bonkers day, we turned in to our hotel rooms. There, I found Glen every bit as miffed by missing the tornadoes as I was. Miff-ery loves company. But not too much, because exhaustion won out and soon I was asleep.